pneumamusic

PN 690 LATIDOS DE AL-ANDALUS

PN 690 LATIDOS DE AL-ANDALUS

No se pudo cargar la disponibilidad de retiro

Índice

Índice

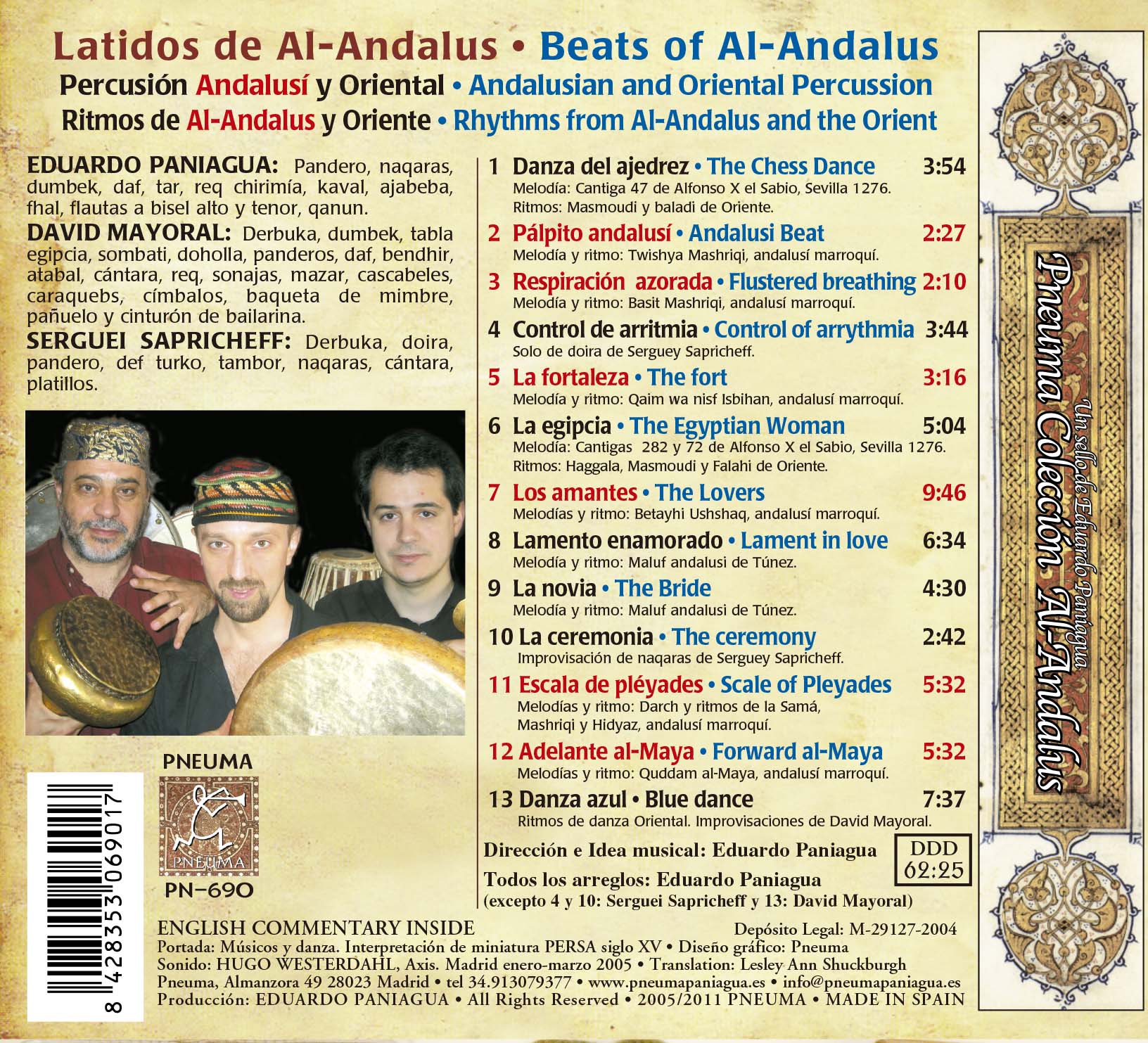

PNEUMA PN-690

LATIDOS DE AL-ANDALUS

Percusión Andalusí y Oriental

Ritmos de Al-Andalus y Oriente

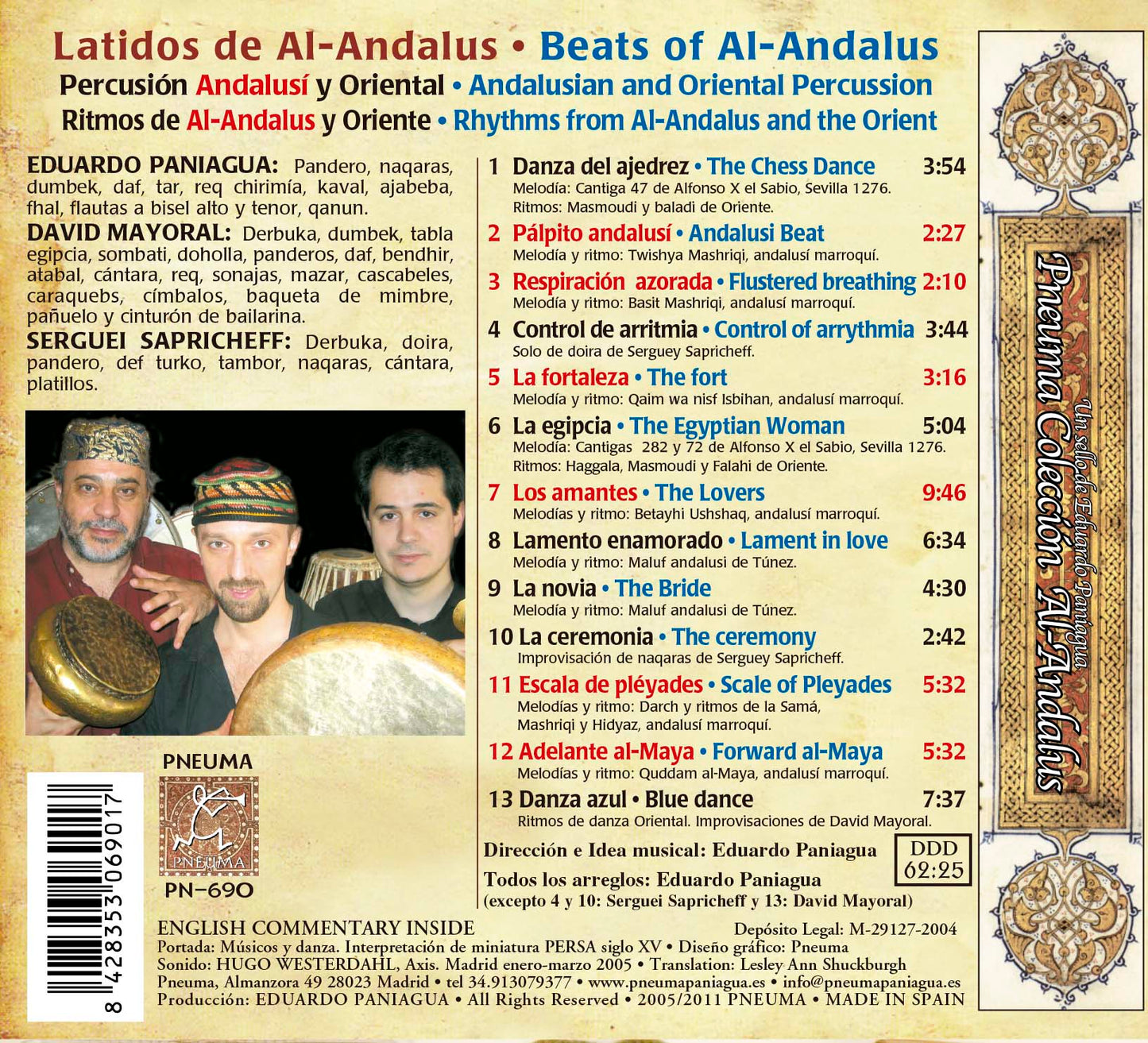

EDUARDO PANIAGUA: Pandero, naqaras, dumbek, daf, tar, req chirimía, kaval, ajabeba, fhal, flautas a bisel alto y tenor, qanun.

DAVID MAYORAL: Derbuka, dumbek, tabla egipcia, sombati, doholla, panderos, daf, bendhir, atabal, cántara, req, sonajas, mazar, cascabeles, caraquebs, címbalos, baqueta de mimbre, pañuelo y cinturón de bailarina.

SERGUEI SAPRICHEFF: Derbuka, doira, pandero, def turko, tambor, naqaras, cántara, platillos.

Abdallah Cheqara: laud (grabación histórica) corte 5

1 Danza del ajedrez • The Chess Dance 3:54

Melodía: Cantiga 47 de Alfonso X el Sabio, Sevilla 1276. Ritmos: Masmoudi y baladi de Oriente. Derbuka, def turco, req y kaval.

2 Pálpito andalusí • Andalusi Beat 2:27

Melodía y ritmo: Twishya Mashriqi, andalusí marroquí. Pandero, dumbek, daf y fhal.

3 Respiración azorada • Flustered breathing 2:10

Melodía y ritmo: Basit Mashriqi, andalusí marroquí.

Derbuka, cántara y flauta a bisel tenor.

4 Control de arritmia • Control of arrythmia 3:44

Solo de doira de Serguey Sapricheff.

5 La fortaleza • The fort 3:16

Melodía y ritmo: Qaim wa nisf Isbihan.

Dumbek, derbuka, pandero, req, laúd y flauta a bisel alto.

6 La egipcia • The Egyptian Woman 5:04

Melodía: Cantigas 282 y 72 de Alfonso X. Ritmos: Haggala, Masmoudi y Falahi de Oriente. Derbukas, pandero, dumbek, atabal, mazar y chirimía.

7Los amantes • The Lovers 9:46

Melodías y ritmo: Betayhi Ushshaq, andalusí marroquí.

Darbukas, doira, tar, cascabeles y qanun

8 Lamento enamorado • Lament in love 6:34

Melodía y ritmo: Maluf andalusi de Túnez. Cántaras, pañuelo de bailarina y kaval.

9 La novia • The Bride 4:30

Melodía y ritmo: Maluf andalusi de Túnez. Derbuka, req, naqaras, daf y ajabeba.

10 La ceremonia • The ceremony 2:42

Improvisación de naqaras de Serguey Sapricheff. Naqaras, , atabal, daf y platillos.

11 Escala de pléyades • Scale of Pleyades 5:32

Melodías y ritmo: Darch y ritmos de la Samá, Mashriqi y Hidyaz, andalusí marroquí.

Derbukas, req, daf, panderos, sonajas, fhal y flauta a bisel alto.

12 Adelante al-Maya • Forward al-Maya 5:32

Melodías y ritmo: Quddam al-Maya, andalusí marroquí.

Derbuka, dumbek, pandero, tar y fhal

13 Danza azul • Blue dance. Ritmos de danza Oriental 7:37

Improvisaciones de David Mayoral. Tabla egipcia, sombati, doholla, bendhir, daf, pandero, req, caraquebs, címbalos, baquetas de mimbre y cinturón de bailarina.

Tiempo total 62:25

Portada: Músicos y danza. Interpretación de miniatura PERSA siglo XV

Sonido: Hugo Westerdahl, Axis. Madrid enero-marzo 2005

Producción: EDUARDO PANIAGUA • 2005

Descripción

Descripción

EL LATIDO DE AL-ANDALUS

Concierto de percusiones arábigo-andalusíes y orientales que rinde homenaje al movimiento del cuerpo en la danza y los sentidos.

Una gran variedad de ritmos y de instrumentos de percusión apoyados por instrumentos melódicos que crean un diálogo musical espontáneo, creativo e inteligente.

El latido de los instrumentos acompaña al latido del corazón del oyente, que no puede evitar el movimiento de sus pies durante la escucha. Un concierto para apasionados del ritmo y la danza que en ocasiones se acerca visualmente al malabarismo.

TIEMPO Y RITMO

Todos hablamos del tiempo y del ritmo, realidades en las que nos sentimos inmersos. Decimos, no tengo tiempo, no me lo permite mi ritmo de vida. Aristóteles define el tiempo como “el número en movimiento”. El tiempo es un movimiento en sentido amplio, cambio, sucesión, duración. Movimiento que puede cortarse, dividirse, numerarse..., por tanto en relación con la corporalidad. Sin cuerpo que se mueva no hay tiempo. Sin tiempo no hay movimiento. El cuerpo humano esta sometido al tiempo. La trascendencia del cuerpo implica la eternidad, el “no tiempo”.

El tiempo se hace concreto a través del ritmo. No se muestra, por tanto, de manera lineal y uniforme, sino marcado por puntos, acentos, “ictus”, o apoyaturas sucesivas. El ritmo no es sólo la subdivisión del tiempo en fragmentos, sino que va además acompañado de una gradación de las intensidades de orden cualitativo, delimitada por los acentos.

El ritmo es la fisonomía del tiempo.

De algún modo la música comenzó con la percusión de un ritmo o el canto ritmado, expresión profundamente humana. El ritmo tiene un efecto tan inmediato sobre nosotros que instintivamente percibimos sus orígenes prístinos (antiguo, primero, primitivo).

El ritmo es un elemento premusical. Se encuentra por doquier en la naturaleza como movimiento ordenado.

EL RITMO MUSICAL

Es una afirmación superficial y muy común decir que la música es ritmo, tomada esta expresión en sentido primitivo como repetición regular y constante de grupos iguales y de igual duración. Sin embargo existe un ritmo verdaderamente musical que no es la repetición continua y conforme de una misma y corta fórmula de construcción simple, sino una relación mucho más compleja y de más alto contenido artístico. Se trata de los valores de los sonidos, en relación con el tiempo, desarrollando su duración sobre un armazón, que es el compás.

Este es el ritmo específicamente musical, constituido por valores que, ni son iguales, ni han de repetirse en grupos como lo requiere el ritmo plástico, o del movimiento físico.

Así, el ritmo de una composición es tanto más puramente musical cuanto es más diferenciado y menos se repita en sus valores individuales o agrupados.

El ritmo primitivo se basa en la división del tiempo en valores de duración exactamente igual. El ritmo musical se apoya en la proporción regular de los acentos fuertes y débiles del compás. Sin exigir la igualdad absoluta de duración entre los valores de las partes o tiempos que componen los compases. Al contrario, más bien demandando una cierta oscilación en el tiempo, dependiente de los acentos rítmicos y melódicos de la frase musical, que no han de corresponder con los tiempos fuera de compás.

Esto quiere decir que las notas de la misma duración teórica no tienen la misma duración al ser interpretadas, porque sobre ellas interviene el acento melódico que varía la intensidad en función de en que parte del compás se encuentren. Estos cambios de duración o modulaciones más o menos profundas pero de una importancia vital para la expresión y el significado de la música, no están indicados en la partitura, porque no tienen representación gráfica y dependen en gran parte de la inspiración del intérprete o del director, si es un conjunto de músicos, por pequeño que sea este.

Paradigma del ritmo musical es el “ritmo elástico” o de la respiración; el latido de la emoción que sigue el dictado orgánico del corazón regido por la emoción. Un pulso en ritmo parecido al de una inhalación profunda de aire, que se retiene un momento y luego se expulsa. Este tipo de ritmo musical se puede coordinar en un conjunto de ejecutantes, cuando escuchándose coordinan y comparten el sentimiento musical. Entonces la música fluye como un organismo vivo, sin que se separen las partes musicales individuales. Entonces la magia de la música nos transporta y volamos sin camino trazado, dejando un rastro impreso en nuestro espíritu.

RÍTMO MUSICAL ÁRABE Y ANDALUSÍ

El ritmo es un elemento básico de la música árabe en general y consecuentemente de la andalusí. No existe espiritualidad sin respiración y toda música profunda tiene su latido rítmico interno. En la música, el cuerpo “tiene derechos” sobre el espíritu humano, y los sentidos son la puerta.

En el siglo VIII, periodo clásico de la música árabe se da un gran avance musical al pasar de la melopea preisláminca, basada en la qasida, a la creación de un ritmo melódico independiente del ritmo poético. Nacen ritmos ligeros adaptados a la forma poética de carácter silábico originándose la rítmica musical como resultado de la métrica poética. La revolución se incrementa con el desarrollo de los instrumentos musicales, los ritmos asimétricos impares y el uso del lenguaje onomatopéyico de la percusión: dum-tak.

En la música árabe-andalusí, no es el tempo o velocidad lo definitorio de los ritmos, sino su aceleración, que presenta cambios sutiles en los esquemas métricos sobre los tiempos pares, los golpes de percusión y los silencios rítmicos, así como los contratiempos y las síncopas.

La música clásica andalusí denominada núba se ordena mediante una serie de movimientos rítmicos secuenciados que no pueden desordenarse ni permutarse y que se diferencian unos de otros por su estructura interna. Estos rítmos básicos al acelerarse el tiempo de su interpretación generan otras formulas rítmicas nuevas que no son arbitrarias.

En la núba conservada en Marruecos se pueden sentir cinco movimientos o mizán (medida), que tiene a su vez tres ritmos según se va acelerando la melodía: el tranquilo (muwashsha) el puente (qantara) y el rápido o salida (insiraf).

Los cinco mizán son: basit (lento), qaím wa nisf (una parte y media), darj (escalera), betayhi (alargado) y quddam (adelante).

La percusión subraya las formulas rítmicas y acentos (iqá´) y no se detiene hasta el final de la obra o en las pausas para dar pié a los solos vocales e instrumentales improvisados.

Otras tradiciones andalusíes del Magreb cambian la denominación y las formulas rítmicas con una riqueza aun mayor.

JUSTIFICACIÓN MUSICAL

La presente grabación toma su base en los ritmos codificados originarios de la tradición andalusí y algún ejemplo de la oriental. Sobre estos ritmos en los que, a pesar de su complejidad, nunca se deja al azar la interpretación, creamos un desarrollo de forma libre. Esto no cambia el esquema oficial tradicional dentro de la núba clásica, donde la melodía es tiranizada por el ritmo, sino que se recrea su potencialidad interna sin romper la coherencia del ritmo con la melodía.

Si hemos sido rigurosos con la tradición en otros trabajos discográficos con la música sufí-andalusí y la obra musical de los poetas de al-Andalus, en esta grabación prima la libertad sobre las herramientas que nos da la tradición. Con los ritmos básicos y los instrumentos apropiados, se aporta algo nuevo a esta tradición.

El método usado es un experimento personal, que justifica el poner nombre nuevo a las obras tradicionales en las que se sustenta. Se basa en la interpretación de la melodía instrumental en el lugar de la parte cantada y la sustitución de la vuelta instrumental por improvisaciones rítmicas, que respetan la métrica y el tiempo de la melodía omitida.

Frente a la idea de un “solo de percusión”, el interpretar las melodías es algo necesario para que se entienda la riqueza rítmica que se crea sobre ellas. Se puede comprender al escucharlas que estas melodías está compuestas para ese ritmo concreto. Pero lo que en esta ocasión se pide al melómano es que no ponga demasiada atención en las melodías, sino que las escuche en segundo plano, como referente para comprender la inteligencia y el timbre de los ritmos, tanto los básicos como los libremente creados sobre esa base.

Con estas advertencias confío en que se dulcifique la posible censura a este trabajo por parte de los expertos en la música tradicional andalusí marroquí, y vean en este esfuerzo un avance creativo sobre esta tradición viva.

Este trabajo no es un muestrario de los ritmos andalusíes, pues quedan muchos por interpretar, sino una demostración creativa de algunos de ellos y de sus posibilidades internas para la improvisación. El latido del corazón es el símil, la imagen que utilizamos, para definir este trabajo, que da lugar a otras imágenes extramusicales como la palpitación, la arritmia benigna y el pulso.

EDUARDO PANIAGUA

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

BEATS OF AL-ANDALUS

Andalusian and Oriental Percussion

Rhythms from Al-Andalus and the Orient

THE BEAT OF AL-ANDALUS

A concert of percussion from Moorish Andalusia and the Orient to celebrate the movement of the body in dance and the senses.

A wide variety of rhythms and percussion instruments backed by melodic instruments that create a spontaneous, creative and intelligent musical dialogue.

The beat of the instruments accompanies the listener’s heartbeat, and your feet cannot stop tapping. A concert for those who are passionate about rhythm and dance, which sometimes looks more like a juggling act.

TIME AND RHYTHM

We all talk about time and rhythm as realities that surround us. Expressions such as “I don’t have time”, “the rhythm of life” are commonplace. Aristotle defines time as “the number of movement”. Time is a movement in the widest sense, change, succession, duration. Movement that can be cut, divided, counted…, in a corporeal sense. Without a body that moves there is no time. Without time there is no movement. The human body is subject to time. The transcendence of the body implies eternity, the absence of time.

Time becomes concrete through rhythm. It does not appear in a linear or uniform manner, but marked by dots, accents, “ictus”, or consecutive appoggiaturas. Rhythm is the physlognomy of time. Rhythm is the subdivision of time into fragments, but these fragments are then further defined by a degree of intensity reflected by the accent.

In a sense music started with the percussion of a rhythm or rhythmic chant, a profoundly human expression. Rhythm has such an immediate effect on us that we instinctively perceive its pristine origin (ancient, first, primitive).

Rhythm is a pre-musical element. It is found everywhere in nature as ordered movement.

MUSICAL RHYTHM

To say that music is rhythm, in the primitive sense of regular and constant repetition of equal groups of equal duration, is a superficial yet common statement. However, there is a truly musical rhythm that is not the continuous and compliant repetition of one short pattern of simple construction, but a much more complex relation of higher artistic content. It is a question of the values of the sounds in relation to time, and the development of their duration on a framework that is the metre.

This is musical rhythm, made up of values that are neither equal, nor repeated in groups as required by the tangible rhythm of physical movement.

Therefore, the rhythm of a composition can be said to be more musical the more diverse it is and the fewer repetitions of values of equal duration it has. Primitive rhythm is based on the division of time into values of equal duration. Musical rhythm depends on the regular proportion of strong and weak beats. It does not require all the note values or beats that make up a bar to be absolutely equal. On the contrary, it demands a certain rhythmic oscillation, achieved through the rhythmic and melodic stress in the musical phrase, but it must never be out of time.

This means that notes of the same theoretical value do not have the same duration when they are played, because melodic stress intervenes to change the intensity of the note according to where it is in the bar. These changes in duration or modulations of greater or lesser intensity are of vital importance to the expression and meaning of the music, and are not indicated in the score because they are not always represented graphically. They depend largely on the inspiration of the performer or of the conductor, in the case of a group of musicians, however small.

The paradigm of musical rhythm is “elastic rhythm” or breathing; the beat of emotion that follows the organic demands of the heart ruled by emotion. A pulse, similar in rhythm to a deep inhalation of air, held for a moment and then expelled. This type of musical rhythm can be synchronised in a group of performers, when they listen to each other and coordinate and share the feeling of the music. Then music flows like a living organism, without the separation of the individual musical parts. The magic of music transports us and we fly without a defined path, leaving a trail printed on our spirit.

ISLAMIC AND ANDALUSI MUSICAL RHYTHM

Rhythm is a basic element in Islamic music in general and consequently in Andalusi music. Spirituality does not exist without breathing and all profound music has its internal rhythmic beat. In music, the body “has rights” over the human spirit, and the senses are the door.

In the 8th century, the classical period for Islamic music, there was a great advance in music from pre-Islamic “melopoeia”, based on the qasida, to the creation of a melodic rhythm independent of poetic rhythm. Light rhythms were born adapted to a poetic form based on syllables, giving rise to musical rhythm as a result of poetic metre. The revolution gained momentum with the development of musical instruments, asymmetric rhythms and the use of the onomatopoeic language of percussion: dum-tak. In Islamic-Andalusian music, it is not the tempo or speed that defines the rhythm, but acceleration. Acceleration brings subtle changes to the metre on the strong beats, the beats of percussion and rhythmic silences, as well as off beats and syncopation.

Classical Andalusi music, the nawbah, is ordered in a sequence through a series of rhythmic movements that cannot be disrupted or rearranged. Each nawbah is characterised by its internal structure. These basic rhythms generate new rhythmic patterns as the tempo accelerates. These new rhythms are not arbitrary.

In the nawbah preserved in Morocco five movements or mizan (measure) can be felt. These in turn produce three new rhythms as the melody accelerates - muwashshah meaning calm, qantara meaning bridge and insiraf meaning fast or departure.

The five mizan are: basit (slow) qaím wa nisf (one and a half parts) darj (steps), betayhi (long) and quddam (forward).

The percussion highlights the rhythmic modes and accents (iqa)and does not stop until the end of the work or in the pauses to introduce the vocal solos and improvised instrumental solos.

Other Andalusi traditions from the Maghreb change the names of the rhythms and their rhythmic formulae enriching them even more.

MUSICAL JUSTIFICATION

This recording is based on written rhythms originally from the Andalusi tradition, and in some cases from the Oriental tradition. We have developed these rhythms in free form, although strictly speaking nothing is ever left to chance in performance, in spite of their complexity. This does not alter the official traditional pattern within the classical nawbah, where the melody is subject to the tyranny of the rhythm. It re-creates its internal potential without breaking the coherence of the rhythm with the melody.

On other recordings, of Sufi-Andalusian music and the musical work of the poets from al-Andalus for example, we have rigorously respected the tradition. On this recording however, freedom takes priority making use of the tools that the tradition gives us. With the basic rhythms and the appropriate instruments, something new can be brought to this tradition.

The method used is a personal experiment that justifies the new names given to the traditional works on which it is based. The instrumental melody is played where the voice should be and the instrumental part is substituted by rhythmic improvisations, that respect the metre and tempo of the omitted melody.

The tunes are performed as percussion pieces to help to understand the rhythmic wealth these melodies contain. The intention is not to present them as “percussion solos”. When you listen to them you can understand that they are composed for a specific rhythm. But on this occasion we ask the listener not to pay too much attention to the melodies but to put them in the background as a reference to understand the intelligence and the timbre of the rhythms, both the basic ones and those created freely on that base.

I hope these explanations will help to palliate the inevitable censure of this work that I will receive from the experts in traditional Moroccan Andalusi music, and that they appreciate my effort to achieve a creative advance on this living tradition.

This recording is not a sample of Andalusi rhythms, as there are still many to be played, but a creative demonstration of some of them and of the possibilities they contain for improvisation. Just as the heartbeat is the simile, the image that we use to define this work, so there are other extra-musical images such as palpitation, benign arrythmia and pulse.

EDUARDO PANIAGUA

Compartir

-

Envío gratis en pedidos mayores a 50 €.

Entrega en 5-7 días laborables para pedidos en España, en el caso de envíos fuera de España el tiempo de envío podría ser algo mayor.

-

Todo el trabajo de Pneuma Music se ha realizado en España.

Música medieval española inédita hasta el momento. Sus discos, con formato Digipack de cubierta de cartón y libreto interior (bilingüe + idioma original), quieren acercarse a una obra de arte total.