pneumamusic

PN 620 ABDESADAQ CHEQARA, MÚSICA ANDALUSÍ, GRABACIÓN HISTÓRICA

PN 620 ABDESADAQ CHEQARA, MÚSICA ANDALUSÍ, GRABACIÓN HISTÓRICA

No se pudo cargar la disponibilidad de retiro

Índice

Índice

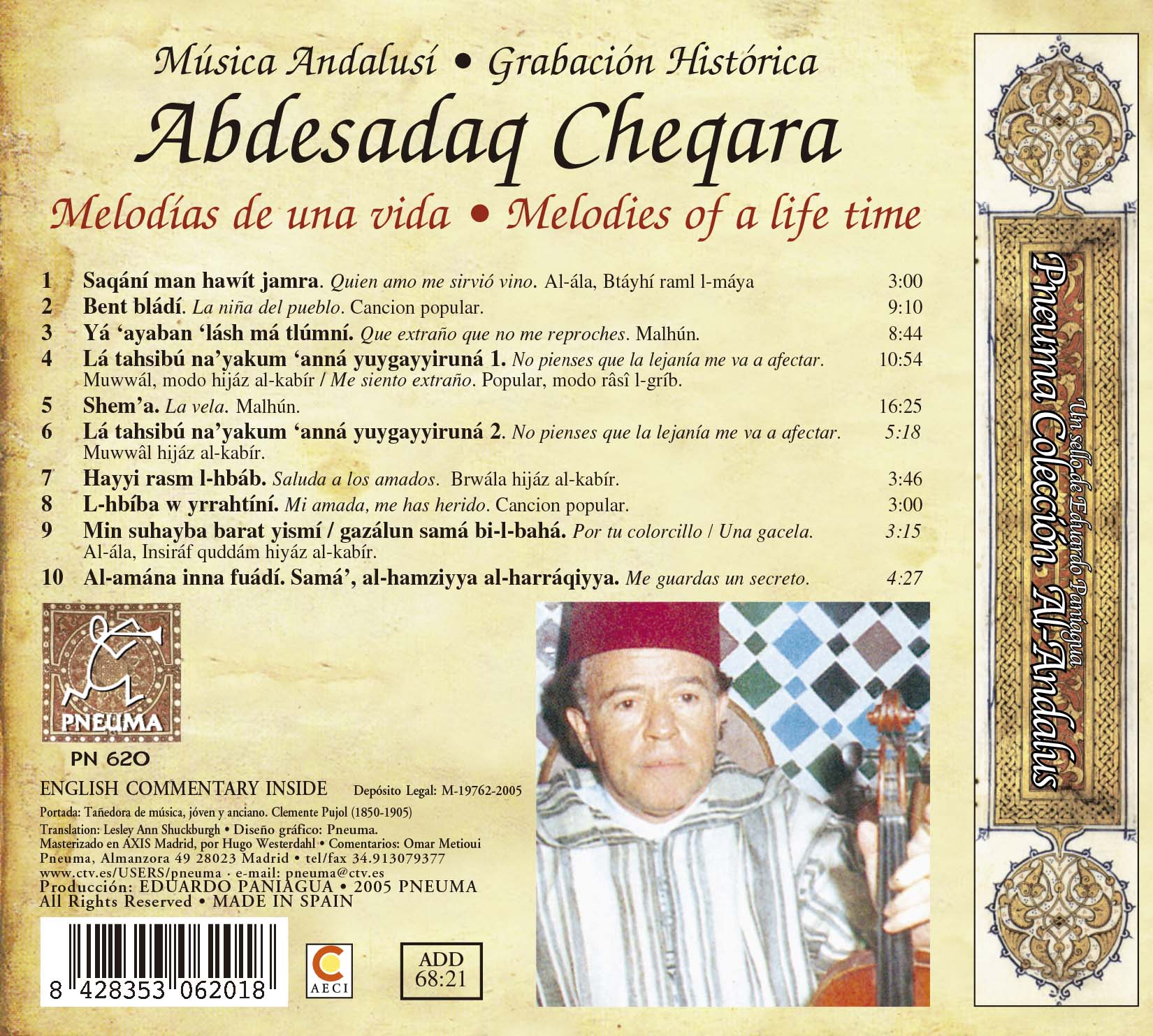

Música Andalusí • Grabación Histórica

ABDESADAQ CHEQARA

Melodías de una vida • Melodies of a life time

1 Saqání man hawít jamra. Quien amo me sirvió vino. Al-ála, Btáyhí raml l-máya 3:00

2 Bent bládí. La niña del pueblo. Cancion popular. 9:10

3 Yá ‘ayaban ‘lásh má tlúmní. Que extraño que no me reproches. Malhún. 8:44

4 Lá tahsibú na’yakum ‘anná yuygayyiruná 1. No pienses que la lejanía me va a afectar. 10:54

Muwwál, modo hijáz al-kabír / Me siento extraño. Popular, modo râsî l-gríb.

5 Shem’a. La vela. Malhún. 16:25

6 Lá tahsibú na’yakum ‘anná yuygayyiruná 2. No pienses que la lejanía me va a afectar. 5:18

Muwwâl hijáz al-kabír.

7 Hayyi rasm l-hbáb. Saluda a los amados. Brwála hijáz al-kabír. 3:46

8 L-hbíba w yrrahtíní. Mi amada, me has herido. Cancion popular. 3:00

9 Min suhayba barat yismí / gazálun samá bi-l-bahá. Por tu colorcillo / Una gacela. 3:15

10 Al-ála, Insiráf quddám hiyáz al-kabír.

Al-amána inna fuádí. Samá’, al-hamziyya al-harráqiyya. Me guardas un secreto. 4:27

ADD 68:21

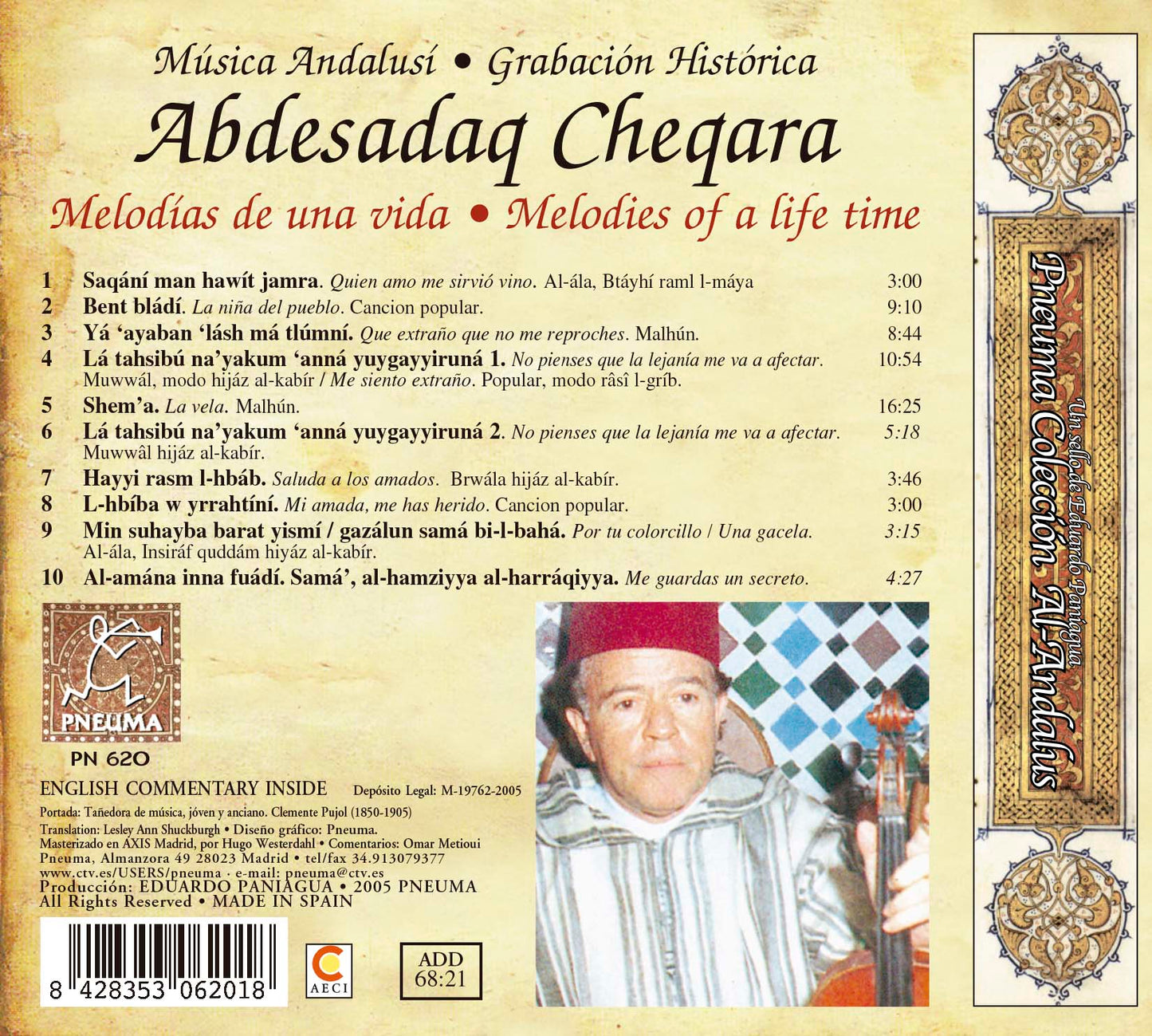

ENGLISH COMMENTARY INSIDE Depósito Legal: M-19762-2005 Portada: Tañedora de música, jóven y anciano. Clemente Pujol (1850-1905)

Translation: Lesley Ann Shuckburgh • Diseño gráfico: Pneuma.

Masterizado en AXIS Madrid, por Hugo Westerdahl • Comentarios: Omar Metioui

Pneuma, Almanzora 49 28023 Madrid • tel/fax 34.913079377

Producción: EDUARDO PANIAGUA • 2005 PNEUMA

All Rights Reserved • MADE IN SPAIN

Música Andalusí • Grabación Histórica

Abdesadaq Cheqara

Melodías de una vida

Abdesadaq Cheqara (1931-1998), ha sido maestro de la música Andalusí (Al-Ala) y virtuoso del violín. Nace en 1931, en la ciudad de Tetuán. Su madre, Assoudia Alharrak, descendía de una familia de poetas, sabios y músicos. Su padre, Abdessalam Cheqara, como laudista y cantante formaba parte de la orquesta de la ciudad junto a otros grandes músicos, dirigidos por el maestro Layashi Lwragli. En esa época, el director del conservatorio era Ben Alamin. Cinco años antes, en 1926, el primer conservatorio de música abrió sus puertas en Tetuán. Más tarde en 1929 fue convertido en escuela privada ofreciendo becas a los ciudadanos.

Cheqara desde muy joven quedó seducido por los cantos religiosos de la cofradía.

""He sido completamente seducido por un personaje místico: Sidi Arafa Al Harrak, sheij de la Zawya Harrakya, que fue desde ese día mi amigo y maestro""

Ese padre espiritual providencial le ofreció su primer laúd y le introdujo precozmente en el mundo de los grandes músicos. Cheqara le recordaba así:

""Cuando salía del Msid (la escuela coránica), me dirigía hacia el local de mi padre, y cuando él se iba a la mezquita o al zoco aprovechaba para tocar los instrumentos de música y para consultar los manuscritos y las obras que trataban del arte musical. Después me dirigía a la casa del sheij Arafa Al Harrak, para terminar mi formación.""

Desde los catorce años, Cheqara formó parte de la orquesta del sheij Arafa con la que viajó mucho y conoció a Abdeslam Allouch, maestro del Malhun, que le enseño este género en el que el ritmo se antepone al texto de las canciones. En 1949 viajó a Fez y a Rabat donde fue recibido por Hadj Mustafa Guedira y durante los años cincuenta actuó tanto con la orquesta de Fez como con la de Casablanca, conociendo a Mulay Ahmed Lukili en la ciudad de Salé. En el concurso organizado para la exposición internacional de Casablanca, Cheqara compartió su éxito como mejor violinista con sus amigos Mohamed Larbi Temsamani, mejor pianista, Chitri, mejor laudista y Mulay Ahmed Lukili, mejor director de orquesta.

El 15 de febrero de 1940 un grupo de personalidades formado por Faquir Hadj Mohamed Dauud, el profesor Aben Abar, Hadj Mohamed ben Larbi Bennuna, Abdeslam Sordo, Ahmed ben Mohamed El Alaui y Abdeslam Al Harrak fueron al palacio del Califa Mulay Hassan ben Mahdi para solicitar un nuevo conservatorio de música Andalusí en Tetuán, que llevaría el nombre de ""Conservatorio Hasani de la música marroquí"". Más tarde en 1957, el Sultán Mohamed V inauguró en Tetuán el nuevo ""Conservatorio Nacional de música y danza"". En ese mismo año Cheqara formó con sus amigos músicos ""La Orquesta del Conservatorio de Tetuán"". Desde entonces, esta orquesta estuvo viajando por Marruecos de festival en festival, y dio la vuelta al mundo como representante de la música Andalusí, cultura milenaria de un pueblo con sed de arte.

En el año 1961 Cheqara comenzó su camino como compositor y, con su violín y su magnífica voz, participó en la grabación de ocho de las once Núbas de la música Andalusí realizadas con patrocinio de la UNESCO en colaboración con la ""Asociación de Aficionados a la Música Andalusí"" de Dris Benjellun Touimi. En 1968 Cheqara, con un cuarteto, colaboró con la agrupación Atrium Musicae de Madrid, dirigida por Gregorio Paniagua, en la grabación de la Antología de la Música Antigua Española de Hispavox-Erato, lo que le dio a conocer en el mundo de la música antigua de Occidente. En 1978 Cheqara fue nombrado Supervisor General del Conservatorio de Tetuán, siendo Temsamani su director. Este amistoso dúo formaría generaciones de músicos, conquistando la simpatía de los melómanos y difundiendo la Escuela de Tetuán entre los amantes de la música Andalusí.

Desde 1956, seducido por los cantos rurales de la región de Tetuán, Cheqara decidió innovarlos sin modificar su ritmo, gracias a lo cual los cantos de las mujeres de Mulay Abdeslam, de Jebel Habib y de Beni Arus se han conservado hasta nuestros días. En 1957, durante la ceremonia de apertura del Teatro Mohamed V de Rabat y en presencia de su majestad el rey, la primera canción popular de Cheqara ""Al habiba jarrahtini” acompañada de bailarinas tetuaníes del conservatorio lideradas por Clara, fue aplaudida con entusiasmo por un público fascinado por el ritmo y la voz de Cheqara. En 1982, Cheqara conoce a José Heredia en Granada y desarrolla la idea de fusionar esta música popular de Tetuán con el cante flamenco. Fruto de este encuentro es la canción ""Bent bladi”, considerada la cima del trabajo de Cheqara en este género.

El repertorio de Cheqara ha sido muy variado, incluyendo la Taqtoqa Jablia y las Qasidas de familias argelinas refugiadas en Tetuán: Ben Drissin, Ben Abdeltefin y Ben Chettab, que él renovó e innovó. La célebre ""Anamalifiach"" desde entonces ha sido un éxito en todas las fiestas.

Con Abdesadaq Cheqara es fácil quedar embelesado. Mohamed El Yamlahi Wazzani decía: “El arco de su violín te acuna sobre las cuerdas, la voz te hechiza, las palabras te van directamente al corazón, y el todo, en una armonía casi divina, te alza por los aires como esa paloma blanca en la cima de las montañas, y te rodea y cerca de paz, de quietud y bienestar”.

Cheqara a los sesenta y un años fue condecorado por el entonces Príncipe Heredero Sidi Mohamed, con el Wisam (galardón) de Caballero del Trono Alaui, ofrecido por el Rey Hasan II en julio de 1992 a los Maestros de la música Andalusí que participaron en la “Grabación integral de la música Al-Ala"".

Tras una larga enfermedad, Abdesadaq Cheqara murió el 31 de octubre de 1998 a la edad de 67 años. Con Temsamani, Lukili, Rais, Brihi, Larbi Syar, Elmtiri, Ahmed Wazzani y otros más, ha pasado a formar parte de la gran familia de la música Andalusí que con estos maestros tuvo su Edad de Oro. Cheqara quedará para siempre como el artista que ha sabido conciliar tradición y modernidad, música de fe y fe de la música, marcando en su época la música de su ciudad.

Eduardo Paniagua

Tomado en parte del texto de Mohamed El Yamlahi Wazzani

Descripción

Descripción

Selección de Canciones

1 Saqání man hawít jamra. Quien amo me sirvió vino. Al-ála, Btáyhí raml l-máya.

Esta obra pertenece al repertorio de la música andalusí (Al-Ala) de Marruecos. Se trata del animoso movimiento final insiráf btáyhí (allegro-vivace-presto) de la tercera fase de la núba Raml l-Maya. En el Cancionero de al-Hayk escrito hacia el año 1800, esta núba estaba escrita sobre la nota RE y con poemas de carácter profano. Un siglo después Abderrahman al-Fassi cambió los poemas amorosos por panegíricos de alabanza al profeta Muhammad. Actualmente en todo Marruecos se canta esta núba, de ambiente mediterráneo y profunda expresividad, en múltiples ocasiones, tanto en fiestas de boda y de circuncisión, como en fiestas religiosas, tales como el peregrinaje, el ramadán y la natividad del Profeta. El vino del primer poema, hace referencia a una bebida celeste, recompensa de Dios a los fieles en el paraíso.

2 Bent bládí. La niña del pueblo. Canción popular.

Esta canción, famosa en todo Marruecos e incluso en algún país vecino como Argelia, corona el maridaje que se ha hecho entre la música andalusí de las dos orillas del mar Mediterráneo. A menudo se ha interpretado intercalada con la “La tarara”, popular canción hispana, desde que así lo hiciera Cheqara junto al cantante flamenco Pepe Heredia. Hoy la siguen cantando todos los grupos que intentan hacer fusión entre lo andalusí y el flamenco. Su texto describe la belleza de la mujer con un estilo muy coloquial propio del norte de Marruecos y su ritmo incita al baile.

3 Yá ‘ayaban ‘lásh má tlúmní. Que extraño que no me reproches. Malhún.

El género Malhún, característico de los artesanos de las grandes capitales de Marruecos como Meknes, Fez y Marrakech, es un derivado de la música andalusí-magrebí, pero con la singularidad de una rítmica propia y, sobre todo, con un género poético de invención marroquí. Las canciones en lengua dialectal (brwal, qsid), tratan en unos casos sobre temas de amor, y en otros describen el proceso para realizar una obra manual de artesanía, conteniendo agudas críticas sociales. También existen temas religiosos, conteniendo el Malhún actuales composiciones que se basan en la tradición, pero abiertas a la comteporaneidad. En la región noroeste de Marruecos: Tánger, Tetuán y Chefchauen, este género no ha tenido muchos seguidores, pero algunos temerarios supieron dar a este tipo de canción un sabor y un color musicalmente más atractivo, gracias al aporte de las familias argelinas que vinieron a refugiarse a Tánger, Tetuán, Rabat y Salé, cuando Francia invadió a su país en 1830. Este poema Yá ‘ayaban ‘lásh má tlúmní tiene como característica el juego de integrar letras en los versos, que cuando se juntan forman las sílabas ba y ha, resultando la palabra hubb, que significa amor. Este juego demuestra el alto nivel literario de la música popular. El ritmo denominado zendani es también típico de nuestra región. Es un ritmo cojo, impar en 5/4, no fácil de controlar para el canto, pero que curiosamente nuestras madres y abuelas lo llevan “en la sangre” y no encuentran ninguna dificultad en moverse dentro de su esquema. Es de lamentar la pérdida de esta tradición a causa de los movimientos degenerativos de la música fácil que nos está rodeando impuesta por una aburrida y mediocre globalización.

Los cortes 4, 6, 7 y 9 pertenecen a la núba Hijaz Kabir, que significa literalmente el gran oriente. Basada en la nota Re, contiene en su escala una segunda aumentada (MI bemol-FA sostenido), lo que le da un sabor muy oriental que encontramos también en alguna de las escalas del cante flamenco.

En los cortes 4, y 6, dos versiones de Lá tahsibú na’yakum ‘anná yuygayyiruná (No pienses que la lejanía me va a afectar), Muwwál, modo hijáz al-kabír, se escucha la influencia de los instrumentos occidentales con el sonido dominante y temperado del piano. Cheqara era muy famoso como experto de la canción popular con influencias andalusíes, traídas de su propia mano. En la música Al-Ala era el segundo músico más famoso dentro de la orquesta de su maestro Mohamed Ben Larbi Temsamani. En esta pieza (corte 6) no toca el piano Temsamani sino ’Awfira, una mujer que pertenecía a la orquesta del maestro Lukili de Rabat. En esta grabación Cheqara intenta demostrar que puede acercarse al maestro Temsamani, reconocido como el mayor virtuoso al piano. También Cheqara en la voz solista, aparte de demostrar su capacidad vocal, imita a Mulay Ahmed Lukili, que fue quien fijó esta forma de cantar a solo dentro del repertorio Al-Ala, en lugar del habitual canto coral.

La canción popular râsî l-grîb (Me siento extraño), al final de la pieza número 4, forma parte de un repertorio conocido bajo la denominación, alála yllálí. Se trata de un cancionero común para hombres y mujeres que puede ser acompañado de la danza. El nombre de este género está tomado de la repetición de sílabas con las que empieza cada canción, similar a los tarareos de las núbas que podemos también encontrar en algunos palos del flamenco.

El corte 9 Min suhayba barat yismí / gazálun samá bi-l-bahá. (Por tu colorcillo / Una gacela), contiene el quddam Insiráf hiyáz al-kabír, que se trata de la última parte del quinto movimiento de esta núba en su fase más rápida.

5 Shem’a. La vela. Malhún.

La canción Shem’a del género Malhún, se hizo muy famosa con el grupo Jiljilala, que al igual que los famosos Nas l-Giwan, vitalizó la tradición con el espíritu y la influencia del movimiento pop de los años setenta. Tanto el texto como la melodía, interpretados en esta grabación por el genial maestro Cheqara, son típicos de nuestra zona del norte y diferentes del resto de Marruecos. Esta pieza, trasportada a la nota LA, da al modo raml l-maya dziriyya’, (modo raml l-maya argelino) un color y un ambiente diferente del original sobre la nota RE.

8 L-hbíba w yrrahtíní. Mi amada, me has herido. Canción popular.

Según cuenta el propio Cheqara esta canción es la primera que le abrió el camino al canto popular. En realidad, uno de los investigadores, compositores y músicos más destacados de Tetuán, Mhemmed Bennouna convenció a Cheqara para estudiar en las montañas de noroeste el repertorio de los jbala, habitantes de las montañas con sangre andalusí en sus venas. Desde aquel entonces con su trabajo y esfuerzo logró salvar parte de esta música. Pero con su bagaje de la música religiosa de la zawya y la música de al-Ala, logró crear una forma urbana de interpretar esta música campesina.

Esta canción fue todo un éxito y le dio a conocer en todo Marruecos como el máximo representante de este género musical.

10 Al-amána inna fuádí. Samá’, al-hamziyya al-harráqiyya. Me guardas un secreto. Inshád, modo al-‘ushsháq.

Poca gente fuera de Tetuán y Tánger conoce a Cheqara como maestro de la sama’, la ceremonia religiosa. Sin embargo, fue gracias a su maestro de la sama’, el sheij de la Zawya Harraqiyya de Tetuán sidi l-Gali al Harraq, el que se iniciara en su carrera musical. Es conocida la relación entre el canto, la danza y el movimiento sufí. Rumi dice “Hay varios caminos para llegar a Dios, yo elegí el de la música y la danza”. De esta relación nace una cierta sacralización de la música que ha permitido la presencia de los instrumentos musicales en las sedes de las cofradías, cosa que no ocurre en las mezquitas. Hasta su muerte Cheqara fue quien dirigía todos los viernes la sesión de sama’ dentro de la Zawya Harraqiyya de Tetuán, donde está enterrado junto a la tumba de su otro maestro, Temsamani.

La Hamziyya es uno de los panegíricos más famosos en todo el mundo árabe. Fue compuesta por Al-Busayri, autor también de la Burda, otro panegírico tan famoso como la Hamziyya.

La composición musical ha sido creada por la familia de al-Harraq. Esta grabación se remonta a 1972, y fue tomada en la zawya por el director en aquella época de la radio nacional de Marruecos, Abdellatif Ahmed Khalis, que era discípulo de la rama de la zawya Harraqiyya de Rabat. Esta música es propia de esta zawya y no se interpreta así en el resto de Marruecos.

OMAR METIOUI

Abdesadaq Cheqara

Melodies of a life time

Abdesadaq Cheqara (1931-1998) was a maestro of Andalusi music (Al-Ala) and a violin virtuoso. He was born in 1931 in Tetuan. His mother Assoudia Alharrak was a descendant of a family of poets, scholars and musicians. His father Abdessalam Cheqara played the lute and sang, together with other great musicians, in the city orchestra that was led by the maestro Layashi Lwragli. At that time, the director of the conservatory of music was Ben Alamin. Five years before, in 1926, the first conservatory of music had opened its doors in Tetuan. Later, in 1929 it was converted into a private school offering grants to the citizens.

From an early age Cheqara was fascinated by the religious chants of the brotherhood.

“I was completely captivated by a mystical personage, Sidi Arafa Al Harrak, sheikh of the Harrakya Zawya, who was from that day on my friend and master”

This providential spiritual father gave him his first lute and was responsible for his precocious introduction to the world of the great musicians. Cheqara remembers it like this:

“When I left the Msid (Quran school), I would go to my father’s place, and when he went to the mosque or the zoco I played the musical instruments and studied the manuscripts and works about the art of music. After that I used to go to sheikh Arafa Al Harrak’s house to finish my education.”

Cheqara became a member of sheikh Arafa’s orchestra at the age of fourteen. He travelled extensively with the orchestra and had the opportunity to meet Abdeslam Allouch, master of the Melhun. It was Allouch who taught him this genre in which more importance is given to rhythm than to the words in a song. In 1949 he travelled to Fez and Rabat where he was received by Hadj Mustafa Guedira, and during the 1950s he performed both in the Fez and the Casablanca orchestras. In Sale he met Mulay Ahmed Lukili. In the competition organised for the Casablanca international exhibition Cheqara shared his success as the best violinist with his friends Mohamed Larbi Temsamani, best pianist, Chitri, best lutenist and Mulay Ahmed Lukili, best conductor.

On 15 February 1940 a group of personalities including Faquir Hadj Mohamed Dauud, the professor Aben abar, Hadj Mohamed ben Larbi Bennuna, Abdeslam Sordo, Ahmed ben Mohamed El Alaui and Abdeslam Al Harrak went to the palace of the caliph Mulay Asan ben Mahdi to ask for a new conservatory of Andalusi music in Tetuan, to be called “Hasani Conservatory of Moroccan Music”. Later, in 1957, the Sultan Mohamed V opened the new “National Conservatory of Music and Dance” in Tetuan. This same year, Cheqara and his friends founded “The Orchestra of the Conservatory of Tetuan” and from then on, the orchestra travelled around Morocco from festival to festival and toured the world representing Andalusi music, a millenary culture of a people thirsty for art.

In 1961 Cheqara embarked on his career as a composer and, with his violin and his magnificent voice, participated in the recording of eight of the eleven nawbahs of Andalusí music, sponsored by UNESCO in collaboration with Dris Benjellun Touimi’s “Andalusi Music Appreciation Society ”. In 1968 Cheqara, together with a quartet, collaborated with Atrium Musicae from Madrid, led by Gregorio Paniagua. Thus, through the recording of the Anthology of Early Spanish Music, produced by Hispavox-Erato he became known in the world of early Western music. In 1978 Cheqara was named General Supervisor of the Conservatory of Tetuan, with Temsamani as director. This friendly duo was to educate generations of musicians, winning the affection of music lovers and spreading the School of Tetuan among lovers of Andalusi music.

In 1956, seduced by the rural songs from the Tetuan region, Cheqara decided to introduce some innovations without changing the rhythm. Thanks to this the women’s songs from Mulay Abdeslam, Jebel Aviv and Beni Arus have been preserved to this day. In 1957, during the opening ceremony of the Mohamed V Theatre in Rabat in the presence of his majesty the king, Cheqara performed his first popular song “Al haviva jarrahtini” accompanied by dancers from the conservatory of Tetuan led by Clara. The song was applauded enthusiastically by the audience fascinated by the rhythm and voice of Cheqara. In 1982, Cheqara met José Heredia in Granada and developed the idea of a fusion of this popular music from Tetuan with Flamenco. The fruit of this meeting is the song “Bent bladi”, considered to be the peak of Cheqara’s work in this genre.

Cheqara’s repertoire was very diverse, and includes the Taqtoqa Jablia and the Qasidas of the Algerian refugee families in Tetuán: Ben Drissin, Ben Abdeltefin and Ben Chettab, which he renovated and innovated. The famous “Anamalifiach” has since been a success at all parties.

It is easy to fall under the spell of Abdesadaq Cheqara. Mohamed El Yamlahi Wazzani said:

“The bow of his violin rocks you on the strings, the voice leaves you spellbound, the words go straight to your heart, and in an almost divine harmony, everything lifts you up in the sky like the white dove on the top of the mountains, surrounding you and enveloping you in peace, quiet and wellbeing”.

At the age of sixty-one Cheqara was presented with the Wisam (prize) of Knight of the Alaui Throne by the then Crown Prince Sidi Mohamed, awarded by King Hassan II in July 1992 to the Maestros of Andalusi music who participated in the “Complete recording of Al-Ala music”.

After a long illness, Abdesadaq Cheqara died on 31 October 1998 at the age of 67. He joined Temsamani, Lukili, Rais, Brihi, Larbi Syar, Elmtiri, Ahmed Wazzani and others in the great family of the Golden Age of Andalusi music. Cheqara will always be the artist who knew how to reconcile tradition and modernity, music of faith and faith in music, bringing the music of his city to the fore in his time.

Eduardo Paniagua

Taken in part from the text by Mohamed El Yamlahi Wazzani

Selection of Songs

1 Saqání man hawít jamra. My loved one served me wine. Al-ála, Btáyhí raml l-máya.

This piece is from the Moroccan Andalusi repertoire (Al-Ala). It constitutes the lively final movement insiráf btáyhí (allegro-vivace-presto) of the third phase of the Raml l-Maya nawbah. In al-Hayk’s Songbook composed in about 1800, this nawbah was written on the note of D and the poems were of a profane nature. A century later Abderrahman al-Fassi changed the love poems to panegyrics in praise of the prophet Muhammad. Today, this nawbah is sung everywhere in Morocco, and is profoundly expressive and Mediterranean. It is performed on many occasions, at wedding receptions or celebrations of circumcision, as well as religious festivals, such as the pilgrimage, Ramadan and birth of the Prophet. The wine in the first poem refers to a heavenly drink, a reward from God to the faithful in Paradise.

2 Bent bládí.The girl from the village. Popular song.

This song, famous all over Morocco and even in some neighbouring countries such as Algeria, crowns the marriage between Andalusi music from both sides of the Mediterranean sea. It is often performed with parts of the popular Spanish song “La Tarara” since Cheqara and the flamenco singer Pepe Heredia combined the two. Today all groups who perform fusion between Andalusi music and flamenco still sing it. The words describe female beauty in a very colloquial style, typical of the north of Morocco, and its rhythm is good to dance to.

3 Yá ‘ayaban ‘lásh má tlúmní. How strange that you do not reproach me. Melhun.

The Melhun genre is typical of the craftsmen in the big cities of Morocco, such as Meknes, Fez and Marrakech. It is derived from Andalusi-Maghrebi music, but has its own unique rhythm and, above all, a poetic genre of Moroccan invention. The songs in dialect (brwl, qsid) are in some cases love songs and in others describe the processes involved in a particular craft, with an element of sharp social criticism. There are also religious themes. The Melhun includes modern compositions based on tradition but open to contemporary influences. In the north east of Morocco, Tangier, Tetuan and Chefchauen, this genre does not have many followers, but some daring people managed to give this type of song a more attractive musical flavour and colour, thanks to the contribution of Algerian families who came to take refuge in Tangier, Tetuan, Rabat and Sale, when France invaded their country in 1830. This poem Yá ‘ayaban ‘lásh má tlúmní arranges the words in the verses so that they make up the syllables ba and ha, forming the word hubb, which means love. This play on words shows the high literary level of popular music. The rhythm known as zendani is also typical of our region. It is an irregular rhythm, in 5/4, and is not easy to sing, but strangely enough our mothers and grandmothers have it in their blood and do not find any difficulty in manipulating its pattern. It is a shame that this tradition has been lost because of the degenerative movements of the easy music that surrounds us imposed by a boring and mediocre globalisation.

Tracks 4, 6, 7 and 9 belong to the nawbah Hijaz Kabir, which literally means the great Orient. Based on the note D, it has an augmented second in its scale (E flat-F sharp) which gives it a very Oriental flavour that is also found in some flamenco scales.

Tracks 4 and 6 are two versions of the Muwwál Lá tahsibú na’yakum ‘anná yuygayyiruná (Do not think that distance will affect me), in hijáz al-kabír mode, in which the influence of Western instruments can be appreciated with the dominant and tempered sound of the piano. Cheqara was very famous as an expert in the popular song with Andalusi influences, which he brought into the repertoire himself. In Al-Ala music he was the second most famous musician in his master Mohamed Ben Larbi Temsamani’s orchestra. In this piece ‘Awfira, a woman who belonged to the orchestra of the maestro Lukili of Rabat, plays the piano, not Temsamani. On this recording (track 6) Cheqara tries to demonstrate that he can come close to the maestro Temsamani, recognized as the greatest piano virtuoso. Cheqara, as solo voice not only demonstrates his vocal ability, but also imitates Mulay Ahmad Lukili, who established this way of singing as a solo within the Al-Ala repertoire, instead of the normal chorus.

The popular song râsî l-grîb (I feel strange), at the end of the fourth piece, is part of the well-known alála yllálí repertoire, which is a songbook for both men and women that can be accompanied by dance. The name of this genre is taken from the repetition of syllables with which each song starts, similar to the tarareo (humming) of the nawbahs that we can also find in some flamenco palos (styles).

Track 9 Min suhayba barat yismí / gazálun samá bi-l-bahá (By your colour/A gazelle), contains the quddam Insiráf hiyáz al-kabír which is the final part of the fifth movement of this nawbah in its fastest phase.

5 Shem’a. The candle. Melhun.

The song Shem’a of the Melhun genre, was made very famous by the group Jiljilala, who like the famous Nas l-Giwan revitalized tradition with the spirit and influence of the pop movement of the seventies. Both the words and the melody, performed on this recording by the ingenious maestro Cheqara, are typical of our area of the north and different to the rest of Morocco. This piece, transposed to A, colours the raml l-maya dziriyya’ mode (Algerian raml l-maya mode) in a way that is different from the original in D, giving a new feel to it.

8 L-hbíba w yrrahtíní. You have hurt me, my love. Popular song.

According to Cheqara himself this song opened the door to folk music for him. In fact, it was one of the most important researchers, composers and musicians in Tetuan, Mhemmed Bennouna who convinced Cheqara to study the repertoire of the jbala, inhabitants of the mountains in the northeast, with Andalusi blood in their veins. From then on, through hard work and effort, he managed to rescue part of this music. But through his background of religious music from the zawya and the music of al-Ala, he managed to create a way of performing this peasant music that is more acceptable in an urban sense.

This song was very successful and made him famous all over Morocco as the best representative of this musical genre.

10 Al-amána inna fuádí. Samá’, al-hamziyya al-harráqiyya. You keep my secret. Inshád, mode al-‘ushsháq.

Few people outside Tetuan and Tangier know Cheqara as a maestro of the sama’, the religious ceremony. However, it was thanks to the maestro of the sama’ the sheikh of the Harraqiyya Zawya of Tetuan sidi l-Gali al Harraq, that he started his musical career. The relationship between song, dance and the Sufi movement is well known. Rumi says “There are several ways to reach God, I chose music and dance”. Through this relationship music has acquired a sacred facet that has allowed the presence of musical instruments in the lodges of the brotherhoods, something which does not occur in the mosques. Until his death it was Cheqara who led the sama’ session within the Harraqiyya Zawya of Tetuan every Friday and it is here that he is buried next to the grave of his other master, Temsamani.

The Hamziyya is one of the most famous panegyrics in the Arab world. It was composed by Al-Busayri, composer of the Burda, another equally famous panegyric.

The musical composition is a creation of the al-Harraq family. This recording was made in 1972 in the zawya by the director of Moroccan national radio at the time, Abdellatif Ahmed Khalis, who was a disciple of the branch of the Harraqiyya Zawya in Rabat. This music belongs to this zawya and is not performed in this way in the rest of Morocco.

OMAR METIOUI

Compartir

-

Envío gratis en pedidos mayores a 50 €.

Entrega en 5-7 días laborables para pedidos en España, en el caso de envíos fuera de España el tiempo de envío podría ser algo mayor.

-

Todo el trabajo de Pneuma Music se ha realizado en España.

Música medieval española inédita hasta el momento. Sus discos, con formato Digipack de cubierta de cartón y libreto interior (bilingüe + idioma original), quieren acercarse a una obra de arte total.