pneumamusic

PN 550 AIRE DE AL-ANDALUS Música andalusí con instrumentos de viento

PN 550 AIRE DE AL-ANDALUS Música andalusí con instrumentos de viento

No se pudo cargar la disponibilidad de retiro

Índice

Índice

PNEUMA PN-550

AIRE DE AL-ANDALUS

Música andalusí con instrumentos de viento

EDUARDO PANIAGUA

AIRE DE AL-ANDALUS

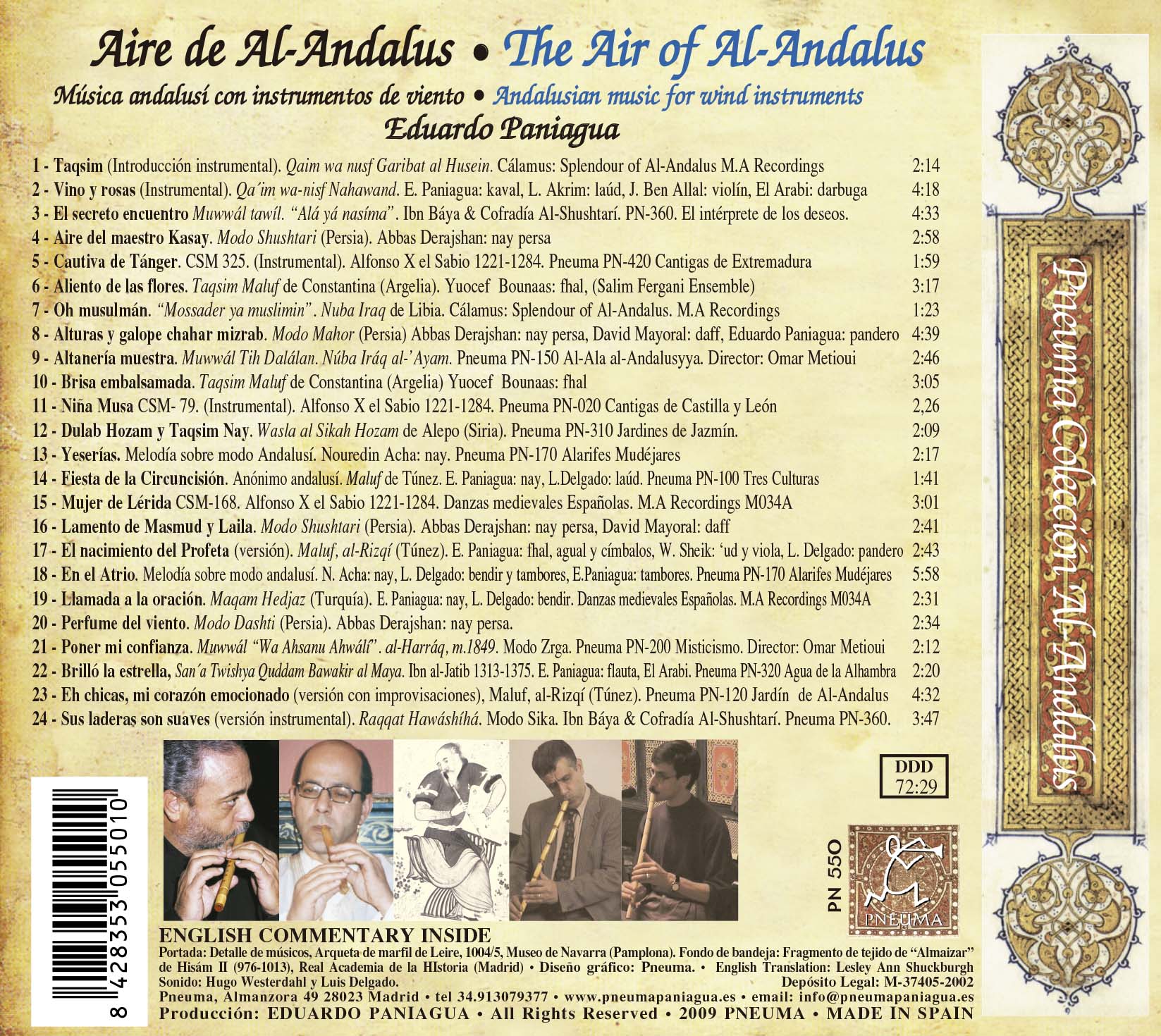

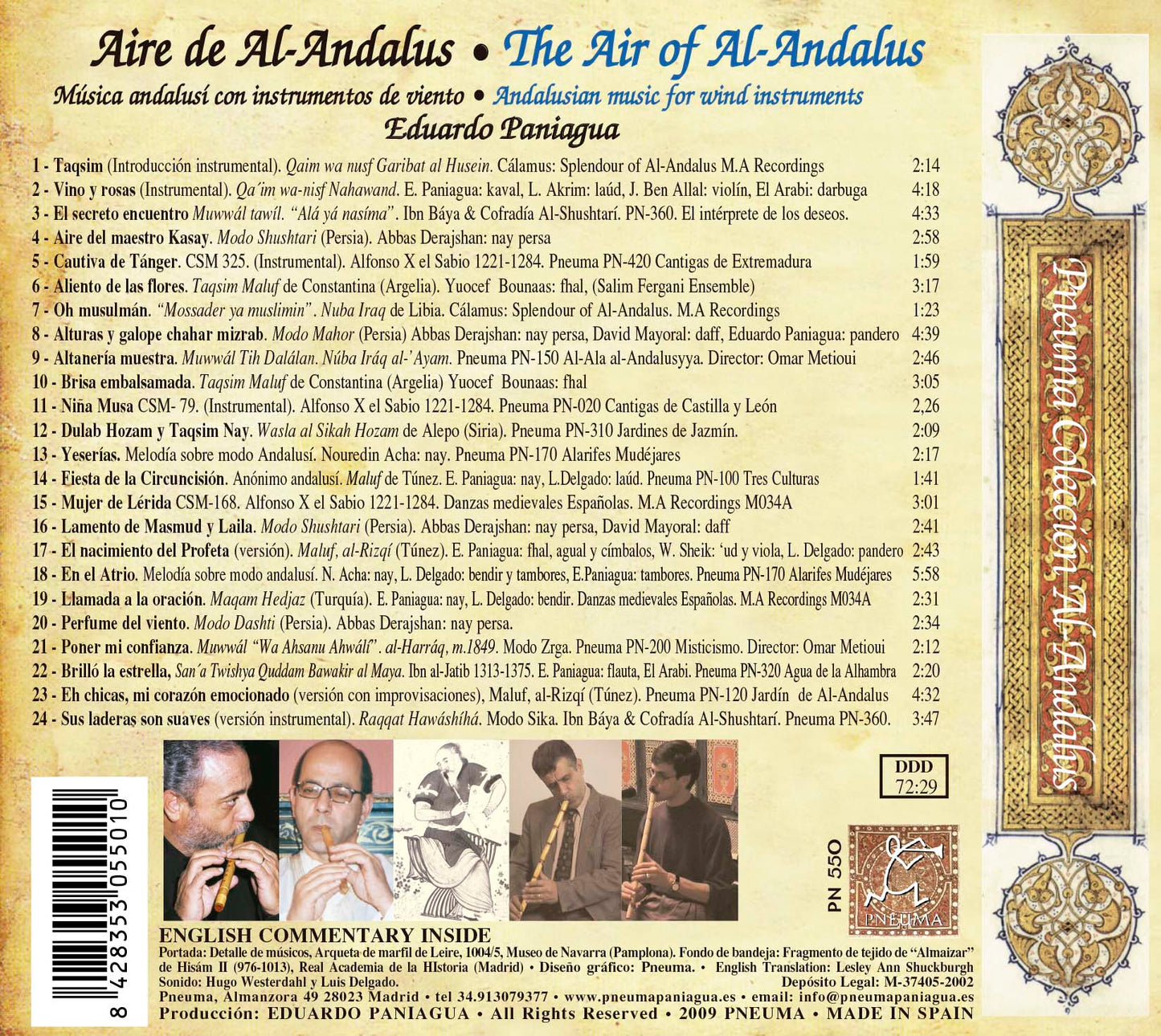

1 - Taqsim (Introducción instrumental). Qaim wa nusf Garibat al Husein 2:14

E. Paniagua: fhal, Begoña Olavide: qanun, L. Delgado: laúd, Rosa Olavide: rabel. C.Paniagua: ajorcas. Cálamus: Splendour of Al-Andalus 1994 M.A Recordings

2 - Vino y rosas (Instrumental). Wine and Roses. Qa´im wa-nisf Nahawand. 4:18

Eduardo Paniagua: kaval, Larbi Akrim: laúd, Jamal Eddine Ben Allal: violín, El Arabi Serghini: darbuga

3 - El secreto encuentro Muwwál tawíl. “Alá yá nasíma”.

The Secret Rendezvous. Modo Raml L-Máya 4:33

Nouredin Acha: nay, Said Belcadi: canto, Omar Metioui:´úd . Ibn Báya & Cofradía Al-Shushtarí. Directores: Omar Metioui & Eduardo Paniagua. Pneuma PN-360. El intérprete de los deseos. Taryuman al-Ashwaq. Ibn ´Arabi (1165- 1240)

¡Oh, soplo de viento, di a las gacelas del Nayd

que soy fiel al pacto que (bien) conocen!

O breeze of the wind, bear to the gazelles of Najd this

message: ‘I am faithful to the covenant which ye know.’

4 - Aire del maestro Kasay. Air of the Master Kasay. Modo Shushtari (Persia) 2:58

Abbas Derajshan: nay persa

5 - Cautiva de Tánger. CSM 325. Captive in Tangier. (Instrumental).

Alfonso X el Sabio 1221-1284 1:59

Eduardo Paniagua: flauta pastoril, David Mayoral: tamburelo, daff y dumbek.

Pneuma PN-420 Cantigas de Extremadura

6 - Aliento de las flores. Breath of Flowers. Taqsim Maluf de Constantina 3:17

Yuocef Bounaas: fhal 1, Bachir Ghouli: tar, Mohamed Bouchareb: derbuka. (Salim Fergani Ensemble)

7 - Oh musulmán. “Mossader ya muslimin” Oh Muslim. Nuba Iraq de Libia 1:23

EduardoPaniagua: flauta, Rosa Olavide: órgano portatil, Luis Delgado: bendir, Begoña Olavide: tar, Carlos Paniagua: darbuga. Cálamus: Splendour of Al-Andalus 1994. M.A Recordings

8 - Alturas y galope chahar mizrab. Heights and gallop chahar mizrab.

Modo Mahor (Persia) 4:39

Abbas Derajshan: nay persa, David Mayoral: daff, Eduardo Paniagua: pandero

9 - Altanería muestra. Muwwál Tih Dalálan. Show hayghtiness.

Núba Iráq al-’Ayam 2:46

Nouredin Acha: nay, Mohamed Aroussi: canto y violín, Omar Metioui: ´ud

Pneuma PN-150 Al-Ala al-Andalusyya. Director: Omar Metioui

Altanería muestra y se altivo.

Pues rango tal te otorga la belleza,

a ti judgar y sentenciar te toca.

Show haughtiness, for you are magnificent!

Since perfection has been granted, you have authority.

10 - Brisa embalsamada. Perfumed Breeze. Taqsim Maluf de Constantina 3:05

Yuocef Bounaas: fhal

11 - Niña Musa CSM- 79. Little Muse. (Instrumental). Alfonso X el Sabio 2,26

Eduardo Paniagua: salamilla (flauta pastoril de caña), Jaime Muñoz: kaval, Luis Delgado: bendir, tar. Pneuma PN-020 Cantigas de Castilla y León

12 - Dulab Hozam y Taqsim Nay. Wasla al Sikah Hozam de Alepo (Siria) 2:09

Tofik al Ramadan: nay • Al Turath Ensemble. Director: Mohamed Hammadye

Pneuma PN-310 Jardines de Jazmín.

13 - Yeserías. Artistic Plasterwork. Melodía sobre modo Andalusí 2:17

Nouredin Acha: nay. Pneuma PN-170 Alarifes Mudéjares

14 - Fiesta de la Circuncisión. Feast of Circumcision.

Anónimo andalusí. Maluf de Túnez 1:41

Eduardo Paniagua: nay y tar , Luis Delgado: laúd y darbuga.

Pneuma PN-100 Tres Culturas

15 - Mujer de Lérida CSM-168. Woman of Lerida. Alfonso X el Sabio 3:01

Eduardo Paniagua: flauta a bisel, Jaime Muñoz: axabeba, Cesar Carazo: viola,

Wafir Sheik: darbuga, Enrique Almendros: tar, Luis Delgado: bendir.

Danzas medievales Españolas. 1995 M.A Recordings M034A

16 - Lamento de Masmud y Laila. Masmud and Laila’s Lament.

Modo Shushtari (Persia) 2:41

Abbas Derajshan: nay persa, David Mayoral: daff

17 - El nacimiento del Profeta (versión). The Birth of The Prophet. Maluf,

al-Rizqí (Túnez) 2:43

Eduardo Paniagua: fhal, agual y címbalos, Wafir Sheik: ‘ud y viola, Luis Delgado: pandero

18 - En el Atrio. In the Atrium. Melodía sobre modo andalusí 5:58

Nouredin Acha: nay, Luis Delgado: bendir y tambores, Eduardo Paniagua: tambores.

Pneuma PN-170 Alarifes Mudéjares

19 - Llamada a la oración. Call to Prayer. Maqam Hedjaz (Turquía) 2:31

Eduardo Paniagua: nay, Luis Delgado: bendir.

Danzas medievales Españolas. 1995 M.A Recordings M034A

20 - Perfume del viento. Perfume of the Wind. Modo Dashti (Persia) 2:34

Abbas Derajshan: nay persa.

21 - Poner mi confianza. Muwwál “Wa Ahsanu Ahwálí”. Place my Confidence.

al-Harráq, m.1849. Modo Zrga 2:12

Nouredin Acha: nay, Mohamed Aroussi: canto, Omar Metioui: ´ud

Pneuma PN-200 Misticismo. Director: Omar Metioui

Poner mi confianza en vuestra gracia

es el mejor de todos mis estados.

The best of my states

is placing my trust in Your grace.

22 - Brilló la estrella, The Star Shone. San´a Twishya Quddam Bawakir al Maya

Ibn al-Jatib 1313-1375 2:20

Eduardo Paniagua: flauta, El Arabi Serghini: pandero y darbuga.

Pneuma PN-320 Agua de la Alhambra

23 - Eh chicas, mi corazón emocionado. Hey girls, my excited Heart. 4:32

(versión con improvisaciones), Maluf, al-Rizqí (Túnez)

Eduardo Paniagua: flauta de caña, Wafir Sheik: ´ud.

Pneuma PN-120 Jardín de Al-Andalus

24 - Sus laderas son suaves (versión instrumental) Raqqat Hawáshíhá,

Its slopes are gentle. Modo Sika 3:47

Ibn Báya & Cofradía Al-Shushtarí. Directores: Omar Metioui & Eduardo Paniagua

Pneuma PN-360. El intérprete de los deseos. Taryuman al-Ashwaq. Ibn Árabi (1165-1240)

Tiempo total 72:29

Sonido: Hugo Westerdahl y Luis Delgado.

Portada: Detalle de músicos, Arqueta de marfil de Leire, 1004/5, Museo de Navarra (Pamplona).

Producción: EDUARDO PANIAGUA • 2004

Descripción

Descripción

Aire de Al-Andalus. Música andalusí con instrumentos de viento.

Eduardo Paniagua recoge en esta selección obras de la tradición andalusí y su entorno interpretadas por él mismo y por otros flautistas de Marruecos, Argelia, Siria, Irán y España. Las grabaciones han sido realizadas en cada correspondiente país.

El protagonismo es para los instrumentos de viento de la familia de las flautas inclinadas tipo nay, kaval o fhal, cuyo sonido, cargado del susurro del viento, nos transporta al extraordinario mundo medieval musulmán.

The Air of Al-Andalus. Andalusian music for wind instruments

Eduardo Paniagua is joined by other flautists from Morocco, Algeria, Syria, Iran and Spain to play works from Al-Andalus (Moorish Andalusia) and the surrounding area. The recordings were made in each corresponding country.

The protagonists are the wind instruments of the flute family such as the nay, kaval or fhal, whose sound is charged with the whispers of the wind which transports us to the extraordinary medieval Muslim world.

AIRE Y MÚSICA

El aire es uno de los cuatro elementos, junto al fuego, agua y tierra, que dan explicación a la realidad física del mundo antiguo y a la anímica del espíritu del hombre medieval.

La música sucede y se transmite en el aire. Aunque tenga como inspiración a otro de los cuatro elementos, la música siempre necesita del aire, tiene como medio subyacente de su ser la movilidad de las notas, de las melodías, de los ritmos en el espacio aéreo. Hay composiciones que simplemente se denomina “aire” musical. Evocación dinámica, movimiento fácil.

La brisa ha tejido una cota de malla con el agua

¡Que hermosa sería sólida para el combate!

Al- Mu´tamid y Rumaykiyya

Aire de al-Andalus nos muestra que la música melismática de las flautas del mundo islámico, al igual que la caligrafía, ofrece mucho más que la simplificación del adjetivo “decorativo”. Con el sonido de la flauta el vuelo dinámico de la música se desenvuelve sin obstáculos en el aire. Traza sus melodiosas curvas imaginarias y nos transporta con ellas venciendo la ley de la gravedad.

Os envío un saludo, con el deseo de una larga vida

como fragancia que perfuma

o como brisa que llega al alba.

Ibn Ruhaym

En sintonía con su intérprete por la dinámica de fluido aéreo, la música tiene que respirar, tiene aliento. Gran parte de la musicoterapia del elemento aire consiste en acompasar la respiración humana al aliento rítmico de la música. Este ejercicio, a veces involuntario en los hombres de temperamento aéreo, produce efectos balsámicos y beneficios físicos y psíquicos.

Una brisa de aire embalsamado al atardecer

ha curado a un enfermo.

¿Se trata de aroma de almizcle o es Valencia

que esparce a lo lejos su delicioso perfume?

Ibn Zaydun

La respiración de la flauta, mejor que en otros instrumentos, manifiesta la evocación de lo innombrable, uno de los cometidos de la música, designando sin palabras lo que es la experiencia contemplativa, trazando un vuelo sustitutivo de lo trascendente.

Que hermosas se muestran las ramas

cuando el viento las entremezcla en estrecho abrazo.

Abúl-l-Hasan Ibn Hafs al-Yazírí

Lo sensible y lo lúdico forman parte ineludible del ser humano de la sociedad islámica clásica, para nosotros medieval. La música y la poesía, unidas de modo especial en la cultura islámica, surgen de la tensión entre lo sagrado y lo profano.

“Cuando una persona sopla con fuerza sobre la embocadura de la flauta y coloca sucesivamente los dedos, los sonidos se escuchan distintos según la cercanía o lejanía de los dedos a la embocadura. No se oye igual al tapar el último orificio que el primero. De igual modo, los demás sonidos entre ambos agujeros son diferentes por su situación respecto al oído, denominándose agudos, dulces, altos o bajos. Cada uno de estos sonidos produce su propia influencia en el alma y en ella encuentran su lugar y su afinidad”.

al-Tawhídí de Bagdad (m. hacia 1010).

MUSULMANES DE AL-ANDALUS

La España musulmana hasta finales del siglo X estuvo sometida culturalmente al criterio del califa de Córdoba. Durante los reinos de taifas, a partir del siglo XI, la inspiración poética y la preocupación intelectual y moral tuvieron su base en la fusión de las tradiciones orientales importadas con las fiestas autóctonas ligadas al ambiente agrícola estacional y a las técnicas artesanales, en feliz conjunción de lo visigodo, árabe, persa, beréber y eslavo, en prolongación étnica con la antigua población autóctona íbero-romana. El elemento persa suministró a las clases dominantes árabes rasgos de civilización.

El sol derrama azafrán sobre las colinas

y dispersa almizcle sobre el fondo de los valles.

Abu-l-Hasan Ibn Siria

El musulmán andalusí siente un profundo amor por la naturaleza y los jardines, marco para la música, danza, declamaciones y cantos de homenaje al amor divino y humano. El sentimiento religioso da rienda suelta al corazón por delante de la voluntad.

La brisa despertaba las cabelleras de las colinas

y la fina lluvia humedecía los rostros de los árboles.

Todo en el jardín, pletórico de vida,

ofrece los colores de sus mantos esmaltados

como un hombre ebrio de felicidad que el viento inclina.

Ibn Jafáya

Para el andalusí el gusto por el lujo y la atmósfera de belleza y magnificencia son indispensable para la vida. Todo ello ilustran el grado de civilización material y artística de la Península Ibérica en el siglo XI.

¿Qué podría perfumarme, si el mencionarte es como sándalo en el ardiente brasero de mi pensamiento?.

Ibn ´Ammár, dirigido a al-Mu´tadid

El Aire de al-Andalus, aire de melodía y canto, se expande como el viento y viaja con los poetas errantes y las esclavas cantoras ejerciendo la influencia de la lengua, el sentimiento y la música de al-Andalus allí donde otros trovadores de occidente y oriente las escuchen.

Observa la luz de su frente, el sonido de sus joyas

y el ámbar oloroso que exhala su cuerpo escondido bajo el manto. Admitamos que esconda su frente

con sus amplias manos y se despoje de sus joyas, pero,

¿de que modo puede suprimir el perfume de su cuerpo?

Al-Mu´tamid

El Aire de al-Andalus une a la música el aire que embalsama el ambiente por el perfume de las flores.

Oh, aliento de las flores, tu viaje nocturno me hace llegar

aroma puro en el soplo embalsamado de marzo.

Ibn ´Abdun

EL NAY (nai, ney)

Es una flauta de caña formada por un tubo hueco biselado por un extremo y que se interpreta en posición oblicua contra los labios para conseguir su sonido al soplar por el extremo superior. También se utilizan otros materiales para su fabricación como: madera, metal y hueso. Tiene seis agujeros en su parte delantera y uno en la trasera, consiguiendo cubrir una tesitura de tres octavas. Al tener una afinación según su dimensión se requieren tamaños diferentes de nay para cubrir las necesidades de modos y tesituras. Tiene muchas variantes y multitud de denominaciones. Algunas de ellas son el kaval (kavala) con escala diatónica o cromática, la qassaba (gasba, axabeba) con sólo 6 agujeros y el fhal, pequeña flauta diatónica usada en el maluf tunecino y argelino.

Su técnica: posición de los labios, intensidad de emisión del aire, forma de ataque, coloración de la sonoridad y textura velada, permiten mucha expresividad y exige un alto grado de virtuosismo. Es el instrumento de viento principal utilizado en la música culta árabe. Sus diferentes timbres y su brillante sonoridad le obliga normalmente a ser instrumento solista.

Su origen se remonta hasta 5.000 años en la cultura egipcia y su localización llega desde Persia y Paquistán hasta Al-Andalus, pasando por Turquía y todo el Magreb. Ha sido utilizado por pastores, por místicos, por derviches para su danza cósmica y por músicos cultos, cubriendo las necesidades de la música tradicional, religiosa y clásica.

El sonido del nay expresa el ansia del hombre por unirse con Dios y se dice que es el alma de la música musulmana.

Eduardo Paniagua

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

THE AIR OF AL-ANDALUS

Andalusian music for wind instruments

AIR AND MUSIC

Air is one of the four elements together with fire, water and earth. The elements represent the physical reality of the ancient world and the spiritual humours of medieval man.

Music is produced in and transmitted through the air. Although it might be inspired by one of the other four elements, music always needs air as the medium through which notes, melodies and rhythms are carried. There are even compositions that are simply called a musical “air”, which evoke motion and easy movement.

The breeze has woven a chain mail coat with the water

How fine it would be for combat!

Al- Mu´tamid y Rumaykiyya

In Air of al-Andalus the melismatic music of the flutes and recorders of the Islamic world is not merely “decorative”, neither is Arabic calligraphy. Through the sound of the flute the music’s dynamic flight unfolds in the air without obstacles. It traces its melodious imaginary curves and takes us with them defying the law of gravity.

I send you a greeting, with the desire for long life

Like a fragrance that perfumes or a dawn breeze.

Ibn Ruhaym

Music must breathe with its performer following the dynamics of the air flow. Music has breath. In musical therapy air as an element is important and many exercises are based on breathing in time to music which is sometimes involuntary in people with an air sign. This has a soothing effect as well as physical and psychological benefits.

A breeze of perfumed air at twilight heals the sick.

Is it the scent of musk or is it Valencia that spreads its delicious perfume from afar?

Ibn Zaydun

The flute breathes in such a way as to evoke concepts that cannot be put into words, perhaps more so than other instruments. This is one of music’s aims – to speak of a contemplative experience without using words, tracing a flight to replace the transcendent.

How beautiful are the branches

When the wind winds them together in a tight embrace

Abúl-l-Hasan Ibn Hafs al-Yazírí

Sensitivity and pleasure are an essential part of the human being in classical (medieval) Islamic society. Music and poetry, united in a special way in Islamic culture, originate in the tension between the sacred and the profane.

“When a person blows hard on the mouthpiece of the flute and puts their fingers in place, the sounds change depending on where the fingers are in relation to the mouthpiece. The sound is not the same when the last hole is covered as when the first hole is covered. In the same way, the rest of the sounds between both holes are different because of their situation in relation to the ear, and are called sharp, sweet, high or low. Each one of these sounds produces its own influence on the soul and finds its place in and affinity with it.”.

al-Tawhídí de Bagdad (d. circa 1010).

MUSLIMS FROM AL-ANDALUS

Muslim Spain towards the end of the 10th century depended culturally on the criterion of the caliph of Cordoba. During the time of the Taifas kingdoms, from the 11th century onwards, poetic inspiration and intellectual and moral considerations were based on the fusion of the oriental traditions that arrived with the local feasts celebrating agricultural seasons and the different crafts. Visigoth, Arab, Persian, Berber and Slav were united in an ethnic prolongation of the ancient Ibero-Roman population. The Persian element provided the dominant Arab classes with features of civilisation.

The sun pours saffron onto the hills

And spreads musk deep in the valleys

Abu-l-Hasan Ibn Siria

The Andalusí Muslim feels a deep love for nature and gardens, providing a background for the music, dance, declamations and chants in homage to divine and human love. Religious feeling gives free reign to the heart over the will.

The breeze woke the hair of the hills

And the fine rain dampened the faces of the trees.

Everything in the garden, plethoric with life,

Offers the colours of its enamelled mantels

Like a man drunk with happiness blown over by the wind ..

Ibn Jafáya

For the Moor from Al-Andalus luxury and the atmosphere of beauty and magnificence are indispensable in life. The degree of material and artistic civilisation in the Iberian Peninsula in the 11th century illustrates this.

What could perfume me, if the very mention

of you is like sandalwood

in the burning brazier of my thoughts?.

Ibn ´Ammár, dirigido a al-Mu´tadid

The air of al-Andalus, air of melody and chant, expands like the wind and travels with the errant poets and the women slave singers taking with it the language, sentiment and music of al-Andalus wherever the troubadours of the West and the East listen.

Observe the light of her forehead, the sound of her jewels and the fragrant amber that her body exhales from under her mantle. Let us admit that she hides her forehead with her broad hands and removes her jewels but how can she suppress the perfume of her body?

Al-Mu´tamid

The air of al-Andalus bonds music to the air that perfumes the atmosphere with the scent of the flowers.

Oh, breath of flowers, your nocturnal journey brings me

The pure aroma in the perfumed breath of March.

Ibn ´Abdun

THE NAY (nai, ney)

The Nay is an end-blown reed flute made from a hollow tube which is bevelled at one end. It is placed at an oblique angle to the lips to produce its sound. It can be made of other materials such as wood, metal or bone. The Nay has six holes in the front and one at the back and has a range of three octaves. Tuning varies according to size therefore a set of nays is needed for different modes and ranges. There are many varieties of nay with different names, such as the kaval (kavala), which produce a diatonic or chromatic scale, the qassaba (gasba, axabeba) with only 6 holes and the fhal, a small diatonic flute used in the maluf in Tunisia and Algeria.

The technique used to play the nay - the position of the lips, the intensity of air blown, the form of attack, the quality of sound and smooth texture- allows the performer to be very expressive and demands great skill. The nay is the main wind instrument used in classical Arab music. Its different timbres and brilliant sound mean that it is usually a solo instrument.

Its origins can be traced back 5000 years to Egyptian culture and it was found everywhere from Persia and Pakistan to Al-Andalus, via Turkey and the Maghreb. It has been used by shepherds, mystics, dervishes for their cosmic dance and classical musicians, and is suitable for traditional, religious and classical music.

The sound of the nay expresses manís longing to be with God and it is said that it is the soul of Muslim music.

Eduardo Paniagua

Compartir

-

Envío gratis en pedidos mayores a 50 €.

Entrega en 5-7 días laborables para pedidos en España, en el caso de envíos fuera de España el tiempo de envío podría ser algo mayor.

-

Todo el trabajo de Pneuma Music se ha realizado en España.

Música medieval española inédita hasta el momento. Sus discos, con formato Digipack de cubierta de cartón y libreto interior (bilingüe + idioma original), quieren acercarse a una obra de arte total.