pneumamusic

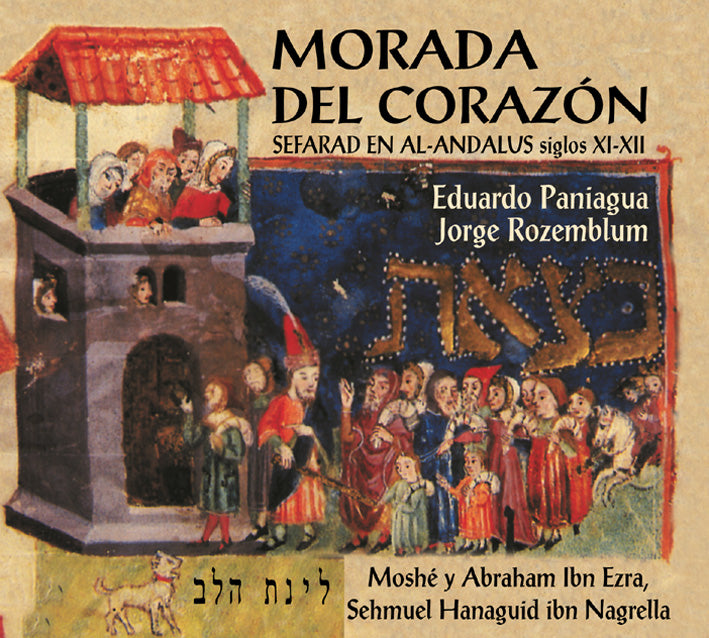

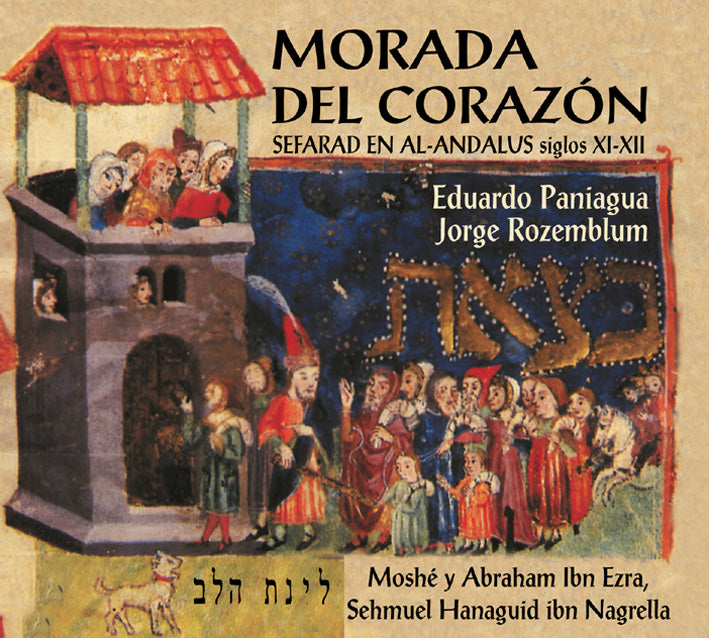

PN 540 MORADA DEL CORAZÓN

PN 540 MORADA DEL CORAZÓN

No se pudo cargar la disponibilidad de retiro

Índice

Índice

MORADA DEL CORAZÓN

SEFARAD EN AL-ANDALUS” Siglos XI-XII

LINAT HALEB

Poemas de la Edad de Oro de Sefarad en al-Andalus con melodías sefardíes y “contrafactas” de música andalusí-magrebí de las cofradías sufíes y de las núbas marroquíes y garnati.

THE HEART’S ABODE

“THE SEFARAD IN AL-ANDALUS” 11th-12th Century

Poems from the Golden Age of the Sefarad in Al-Andalus with Sephardic melodies and “contrafacta” pieces from the Andalusí-Magrebí music of the Sufi brotherhoods and from the Moroccan and Garnati nawbas.

PN-540

MÚSICA ANTIGUA – SEFARAD. Director: Eduardo Paniagua

JORGE ROZEMBLUM Canto 1, recitado, coro y cítola

CESAR CARAZO Canto 2, coro y fídula

EDUARDO PANIAGUA Coro, qanun, flautas, cálamo, fhal, darbugas,

tambor con tensores, tar, sistro, gong y palmas

WAFIR SHEIK Laúd, suisen, setar y palmas

DAVID MAYORAL Pandero, dumbek, darbuga, daf y riq

1 Oración de Januká • A Hanukkah Prayer. Tradicional sefardí. 2:36

2 Dedicación del Templo, Salmo 30 de David 2:39

The Dedication of the Temple. Anónimo de Salónica.

3 Meditaré en la Torá • I shall meditate on the Torah. (Instrumental) 3:34

4 “Ky eshmerá shabat” • Si observo el sábado 3:57

If I observe the Sabbath. Abraham Ibn Ezra (1089-1167).

5 La conversión del judío • The Conversion of the Jew. (Instrumental). 3:37

Alfonso X el Sabio (1221-1284)/E. Paniagua.

6 “Mi tejilá ‘ása” • Dios al comienzo 2:49

God in the Beginning. Shemuel Hanaguid ibn Nagrella (993-1055).

7 Shabat sagrado • The Sacred Shabbat. (Instrumental). 3:02

Judería de la región otomana.

8 “Esh Ahabim” • Fuego de pasión 3:37

Fire of Passion. Shemuel Hanaguid ibn Nagrella (993-1055).

9 Descansad en shabat • Rest on Shabbat. (Instrumental). Melodía yemenita. 2:29

10 “Asher lo yam” • Tuyos son los mares 10:45

Yours are the Seas. Shemuel Hanaguid ibn Nagrella.

11 “‘Al ma’atzabí” • Mi corazón se queja 4:49

My Heart Aches. Moshé ibn Ezra (h.1055-h.1135).

12 “El Neerátz” • Oh, Dios terrible 5:33

Oh, Terrible God. Shemuel Hanaguid ibn Nagrella (993-1055).

13 “Ketanot pasim” • Túnica de rayas 3:33

Striped Tunic. Moshé ibn Ezra (h.1055-h.1135).

Tiempo total: 53:31

Grabado en Madrid, Marzo-Mayo 2003 por Hugo Westerdahl

Selección de poemas, melodías e instrumentación: Eduado Paniagua.

Adaptación de textos hebreos y pronunciación: Jorge Rozemblum.

Portada: ""Moisés saca a los hebreos de Egipto”. Hagadá Kaufmann, España s. XIV Traducciones: Jorge Rozemblum (1,2,4), Ángel Sáenz Badillo y Judith Targarona (6,8,10,12) y Rosa Castillo (11-13). Traslation: Lesley Ann Shuckburgh

Producción: EDUARDO PANIAGUA

All Rights Reserved • 2003 PNEUMA • MADE IN SPAIN

Descripción

Descripción

SEFARAD EN AL-ANDALUS

A partir del año 711 España entró en el seno de “Dar al-Islam” (La Casa del Islam), y los judíos y cristianos (arrianos y católicos), se integraron en el nuevo estado musulmán. Los judíos españoles se reencontraron con sus hermanos de Oriente y África del Norte a través del dominio socio-cultural y económico musulmán. En el año 863 el emir cordobés Muhammad I establece el estatuto de la fraternidad de musulmanes, judíos y cristianos (mozárabes), “gentes del Libro”. A la sombra de la Media Luna los judíos lograron un renacimiento de su cultura, del idioma hebreo y de sus costumbres, alcanzando una edad dorada de su poesía y ciencia. A partir del reinado de Abderrahmán III (912-961) y hasta el siglo XII, personalidades judías pertenecieron a la élite cortesana: visires, consejeros, médicos, astrónomos, filósofos y poetas, encumbraron su cultura haciendo renacer el hebreo como lengua literaria. A comienzos del siglo XI, con la caída del califato cordobés y el florecimiento de los reinos de taifas, la cultura hispano-judía alcanzó su mayor esplendor, destacando las comunidades asentadas en Granada y Zaragoza. La irrupción de los musulmanes africanos almorávides (1090-1147) y almohades (1147-1232), no sólo retrasó el avance de la reconquista de castellanos y aragoneses, sino que rompió el clima de tolerancia y convivencia de las “gentes del Libro” forzando a la conversión al Islam o al exilio de judíos y mozárabes. Con los almohades, los sabios filósofos y científicos, tanto musulmanes como judíos, fueron censurados y sus libros quemados. Es el caso de Ibn Rushd-Averroes (1126-1198) y de Maimónides (1135-1204), este último obligado a buscar refugio en Egipto. Otros judíos se instalaron bajo la protección de los reyes cristianos iniciando la fase histórica de Sefarad en los Reinos cristianos, o su permanencia en la Granada nazarí (1232-1492).

RENACIMIENTO DE LA CULTURA HEBREA

Desde la destrucción del Templo, los rabinos judíos prohibieron las exhibiciones de alegría que no se circunscribieran al ámbito litúrgico, entre ellas la música. Además de las músicas profanas, quedó proscrito en las sinagogas todo instrumento que no fuera el shofar, el cuerno de carnero, cuyo significado extra-musical simboliza la Alianza entre Dios y su pueblo. Su sonido, terrible a los oídos de los creyentes, favorece la atmósfera de penitencia que exigen festividades como Rosh Hashaná (inicio del año judío), Yom Kipúr (día del arrepentimiento) o, en el caso de los ritos de los judíos sefardíes y yemenitas, los servicios matinales del mes que precede al final de año.

En el siglo IX de la era cristiana, la escuela de Tiberíades (Palestina) de la mesoráh culminó la creación de un sistema completo y coherente de símbolos para la lectura entonada de los textos bíblicos (ta’améi mikráh o cantilena), aunque la interpretación de los mismos signos varía en gran medida entre las distintas comunidades judías de la Diáspora.

Además de la Torah y la legislación religiosa contenida en la Mishná y el Talmúd, la literatura mística del Hejalot y la poesía de las oraciones de la liturgia sinagogal son las muestras de las manifestaciones literarias de la antigüedad judía.

MORADA DEL CORAZÓN

Pese a las prohibiciones, el ambiente permisivo y hedonista de los gobernantes musulmanes en la Península Ibérica, donde había a su llegada una comunidad judía relativamente importante, favoreció el cruce cultural.

En el siglo X en al-Andalus, y especialmente en la ciudad de Córdoba, es donde se produce un renacimiento de los judíos a la ciencia y a las humanidades. Córdoba, rivalizando con Bagdad, se convirtió en “la casa de las ciencias” (dar al-ulum) con fama en toda Europa. Los judíos de al-Andalus tuvieron acceso a este saber y por primera vez escribieron sobre ciencia, gramática y filosofía. Comenzaron a escribir poesía sin finalidad religiosa, por la belleza de la expresión lingüística dedicada a la naturaleza, a los placeres y al entretenimiento de los sentimientos.

Jasdáy ben Saprut (h.910-970), médico de la corte, fue considerado príncipe (nasí) de las comunidades judías, dedicándose especialmente a elevar su nivel cultural. Invitó a Córdoba a los primeros poetas conocidos y pioneros en los estudios gramaticales en hebreo, Dunásh ben Labrat (Fez-Córdoba) y Menajem ben Saruq (Tortosa-Córdoba).

El hebreo había dejado de hablarse en el siglo II, sobreviviendo en la literatura y como segunda lengua interna en las familias. En al-Andalus y en esta época se dio el importante fenómeno de la recuperación del hebreo bíblico ampliando su vocabulario con neologísmos semánticos del árabe para la poesía, utilizando el árabe para la prosa.

Dunásh ben Labrat, gracias a su conocimiento de la poesía árabe, introdujo en la nueva poesía hebrea, no sin ser por ello duramente criticado, el metro cuantitativo y la estructura de la casida árabe y la moaxaja andalusí, con nuevos contenidos religiosos e incluyendo además temas y contenidos profanos.

Durante los efímeros reinos de taifas de gran tolerancia religiosa, el talento de los judíos produjo la denominada “Edad de Oro” de la cultura hispano-hebrea.

Shemuel ibn Nagrella (993-1055), nacido en Córdoba, sin abandonar los temas científicos, ni la legislación y la filología hebrea, destacó en los campos político y literario, siendo visir del rey Badis de Granada. Su colección de poemas recoge todo tipo de géneros que se cultivaban en la poesía árabe además de las obras sobre sus victorias como jefe del ejército.

Con Shelomó ibn Gabirol (Málaga h.1020-h.1057) la poesía religiosa alcanza las más elevadas cotas de lirismo. Ishaq ibn Gayat (Lucena 1038-1089) destacó en la literatura rabínica y sinagogal. Su discípulo Moshé ibn Ezra (Granada h.1055-h.1135) fue poeta y crítico en la Granada de ibn Nagrella. Invitó a su amigo poeta Yehudá ha-Leví (Tudela h.1070-1141) y de esta época es su “Libro del collar (Séfer ha-Anaq)” en el que trasladó hábilmente a la lengua hebrea la técnica y temas de la poesía árabe. A causa de la invasión de los almorávides en 1090 se exilió, escribiendo en árabe la obra filosófica “Arriate de aromas” traducida al hebreo como “Arugat ha-bósem” y su preceptiva poética “Libro de la disertación y el recuerdo”. Su poesía religiosa y secular consiguió la perfección formal según los cánones de la época.

Abraham ibn Ezra (Tudela 1089-Calahorra1164) cultivó todos los géneros poéticos introduciendo por vez primera el reflejo de la vida cotidiana. Gramático, filósofo, astrónomo, matemático y poeta, viajó por varios reinos europeos difundiendo la cultura judeo-andalusí y escribiendo numerosos tratados sobre la sabiduría que dominaba.

Otros poetas y filósofos de esta época de los taifas son: Yosef ibn Saddiq (Córdoba, m. 1149), Bajya ibn Paquda (Zaragoza) y Abraham bar Jiya (Barcelona, m.1136). En el periodo almohade vivieron el éxodo hacia los reinos cristianos o hacia Oriente: Abraham ibn Daúd, establecido en Toledo y el cordobés “Maimónides” Moshé ben Maimón (1138-1204) errante por al-Andalus, Marruecos y Egipto.

También la música se ve influenciada por los nuevos poemas profanos, aunque de inspiración generalmente religiosa (piyutím), que nacen de la pluma de estos grandes de la poesía judeo-andalusí. A pesar de que no han llegado a nosotros las melodías utilizadas en esos tiempos (siglos X-XII), sabemos por la literatura de la época que entonces era práctica común la contrafacta, es decir, la utilización de una melodía popular de fuente ajena (musulmana o cristiana) como base para cantar textos en hebreo. La influencia externa llega incluso a la adopción de formas musicales como la suite de poemas árabes de la núba, transformada en las bakashót que los judíos sefardíes aún entonan de madrugada en fiestas señaladas.

Hemos utilizado emotivas melodías de la tradición andalusí-magrebí, tanto del ámbito de las cofradías sufíes, como de la música aristocrática de las núbas de tradición marroquí y garnati de Argelia. No hemos rechazado algunas melodías del repertorio “mudejar” de las cantigas de Alfonso X el Sabio, que tal vez pudieron ser a su vez contafactas de canciones anteriores en el tiempo.

TRANSLITERACIÓN DEL HEBREO AL ESPAÑOL

Las fuentes referidas a la música judeo-española medieval y en general a textos hebreos suelen tener unas transliteraciones cercanas a la lengua inglesa. De esa manera, han trascendido al español de manera errónea términos de difícil pronunciación. Para facilitar la lectura y pronunciación correctas a los no iniciados en la lengua hebrea, hemos preferido utilizar unas transliteraciones más cercanas al español, viéndonos obligados a incluir un mínimo de signos y combinaciones ortográficas ausentes de nuestro idioma.

Jorge Luis Rozemblum Sloin y Eduardo Paniagua

THE SEFARAD IN AL-ANDALUS

From the year 711 Spain became part of “Dar al-Islam” (The House of Islam), and Jews and Christians, Arians and Catholics were integrated into the new Muslim state. Muslim socio-cultural and economic control meant that Spanish Jews were reunited with their brothers from the Orient and North Africa. In 863 the Emir of Cordoba Muhammad I established the statute of the brotherhood of Muslims, Jews and Christians (Mozarabs, Spanish Christians living in Muslim Spain), the “peoples of the Book”. Under the Half Moon Jewish culture, the Hebrew language and Jewish customs enjoyed a renaissance, reaching a Golden Age of poetry and science. From Abderrahman III’s reign (912-961) until the 12th century there were Jews among the elite at court: viziers, counsellors, doctors, astronomers, philosophers and poets who brought dignity to their culture and the Hebrew language was reborn as a language of literature. At the beginning of the 11th century, with the fall of the Caliphate of Cordoba and the flourishing of the taifas, the Hispano-Jewish culture reached the height of splendour, particularly in the communities in Granada and Zaragoza. The arrival of the African Almoravid (1090-1147) and Almohad (1147-1232) Muslims not only held back the advance of the Castilian and Aragonese reconquest, but broke the climate of tolerance and cohabitation of the “peoples of the Book” forcing the Jews and Mozarabs to convert to Islam or to go into exile. With the Almohads, the wise philosophers and scientists, both Muslim and Jewish, were censored and their books were burnt. This was the case for Ibn Rushd-Averroes (1126-1198) and Maimonides (1135-1204), who had to seek refuge in Egypt. Other Jews settled under the protection of the Christian kings and so the historic Sefarad phase of the Christian Kingdoms began, the presence of the Jews in the Granada of the Nazarí dynasty (1232-1492).

RENAISSANCE OF THE HEBREW CULTURE

After the destruction of the Temple, the Jewish rabbis forbade all forms of enjoyment that were not part of the liturgy, including music. Profane music and all instruments other than the shofar, the ram’s horn which symbolizes the Alliance, were banned from the synagogue. The sound, terrible to the ears of the believers, creates the atmosphere of penitence required by festivities such as Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year), Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement) or, in the case of the Sephardic and Yemenite Jewish rites, the matins services of the month before the end of the year.

In the 9th century of the Christian era, the school of Tiberiades (Palestine) of the mesoráh culminated in the creation of a complete and coherent system of symbols for the chanting of biblical texts (ta’améi mikráh or cantillation), although the interpretation of the same symbols varies greatly in the different Jewish communities of the Diaspora.

Apart from the Torah and the religious legislation contained in the Mishnah and the Talmud, the mystical literature of the Hejalot and the poetry of the prayers of the liturgy of the synagogue are all that remain of literature from the Jewish ancient times.

THE HEART’S ABODE

In spite of the prohibitions, the permissive and hedonistic atmosphere of the governing Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula, where there was already a relatively important Jewish community, favoured cultural interchange.

In 10th century Al-Andalus, and especially in the town of Cordoba, there was a reawakening to science and the humanities among the Jews. Cordoba, rival to Baghdad, became “the house of science” (dar al-ulum) famous in all of Europe. The Jews from Al-Andalus had access to this knowledge and for the first time wrote about science, grammar and philosophy. They began to write poetry for its linguistic beauty , turning to subjects such as nature and the delights and entertainment of the senses, rather than just for

religious ends.

Hasday ben Saprut (910-970), court physician, was considered the prince (nasí) of the Jewish communities, and he spent much of his time devoted to improving the level of culture. He invited Dunash ben Labrat (Fez-Cordoba) and Menahem ben Saruq (Tortosa-Cordoba) the first known poets and pioneers in grammatical studies in Hebrew, to Cordoba. Hebrew had not been spoken since the 2nd century, surviving only in literature and as a second language in the home. At this time Al-Andalus witnessed the important phenomenon of the recuperation of biblical Hebrew and the vocabulary expanded with semantic neologisms from Arabic used in poetry, whilst Arabic itself was used for prose. Through his knowledge of Arabic poetry Dunash ben Labrat introduced verses and the structure of the Arabic qasida and the Andalusi moaxaja into the new Hebrew poetry, but not without harsh criticism.

During the ephemeral time of the taifas kingdoms when there was great religious tolerance, the talent of the Jews gave rise to the “Golden Age” of Hispano-Hebrew culture.

Shemuel ibn Nagrella (993-1055) born in Cordoba, was Vizier to king Badis of Granada and stood out in both politics and literature. His collection of poems includes works on his victories as chief of the army as well as the full range of genres that were cultivated in Arabic poetry. He also worked on scientific matters, legislation and Hebrew philosophy. With Shelomo ibn Gabirol (Málaga c.1020-c.1057) religious poetry reached its height. Ishaq ibn Gayat (Lucena 1038-1089) stood out in rabbinic poetry and the poetry of the synagogue. His disciple Moshe ibn Ezra (Granada c.1055-c.1135) was a poet and critic in the Granada of ibn Nagrella. He invited his poet friend Yehuda ha-Levi (Tudela c.1070-1141) to Granada and his “Book of the Necklace (Sefer ha-Anaq)” is from this period. In this work he cleverly applied the technique and themes of Arabic poetry to the Hebrew language. After the invasion of the Almoravids in 1090 he went into exile, and wrote the philosophical work “Arriate de aromas” (“Flower bed of Smells”) in Arabic, translated into Hebrew as “Arugat ha-bosem”, and his poetic rulebook “Book of Dissertation and Remembrance”. His religious and secular poetry achieved perfection of form according to the canons of the time.

Abraham ibn Ezra (Tudela 1089-Calahorra1164) dominated all the existing poetic genres and introduced reflections on everyday life. Grammarian, philosopher, astronomer, mathematician and poet, he travelled around different European kingdoms spreading Jewish-Andalusí culture and writing treatises on the subjects on which he was an expert. Other poets and philosophers of this time of the taifas included Josef ibn Saddiq (Córdoba, m. 1149), Bajya ibn Paquda (Zaragoza) and Abraham bar Jiya (Barcelona, m.1136). In the Almohad period they too were part of the exodus towards the Christian kingdoms or to the Orient: Abraham ibn Daud, settled in Toledo and “Maimonides” Moshe ben Maimon (1138-1204) from Cordoba, travelled around Al-Andalus, Morocco and Egypt.

Although generally inspired by religious themes (piyyutim), music was also influenced by the new profane poems that flowed from the pens of these great men of the Golden Age of Jewish-Andalusi poetry. In spite of the fact that the melodies of the time do not survive today (10th-13th centuries), we know through the literature of the time that contrafacta was common practice at the time, that is the use of a popular melody from a different source (Muslim or Christian) as a base to sing the texts in Hebrew. This external influence is even encountered in the adoption of musical forms such as the suite of Arabic poems of the nawba, transformed in the bakashot that the Sephardic Jews still sing on the morning of certain celebrations.

We have used emotive melodies from the Andalusí-Magrebí tradition, both from the Sufi brotherhoods and the aristocratic music of the nawbas of Moroccan and Garnati tradition from Algeria. We have also realised that some melodies from the “mudejar” repertoire of the cantigas of Alfonso X the Wise, could also have been contrafacta of songs from former times.

TRANSLITERATION OF HEBREW TO SPANISH

The sources found for medieval Jewish-Spanish and in general Hebrew texts are usually in transliterations heavily influenced by English. Therefore, terms that are difficult or wrongly pronounced have found their way into Spanish. To facilitate correct reading and pronunciation for those who have no knowledge of the Hebrew language, we have preferred to use a transliteration closer to Spanish, and so have endeavoured to include a minimum of symbols and spelling combinations not used in our language.

Jorge Luis Rozemblum Sloin y Eduardo Paniagua

Compartir

-

Envío gratis en pedidos mayores a 50 €.

Entrega en 5-7 días laborables para pedidos en España, en el caso de envíos fuera de España el tiempo de envío podría ser algo mayor.

-

Todo el trabajo de Pneuma Music se ha realizado en España.

Música medieval española inédita hasta el momento. Sus discos, con formato Digipack de cubierta de cartón y libreto interior (bilingüe + idioma original), quieren acercarse a una obra de arte total.