pneumamusic

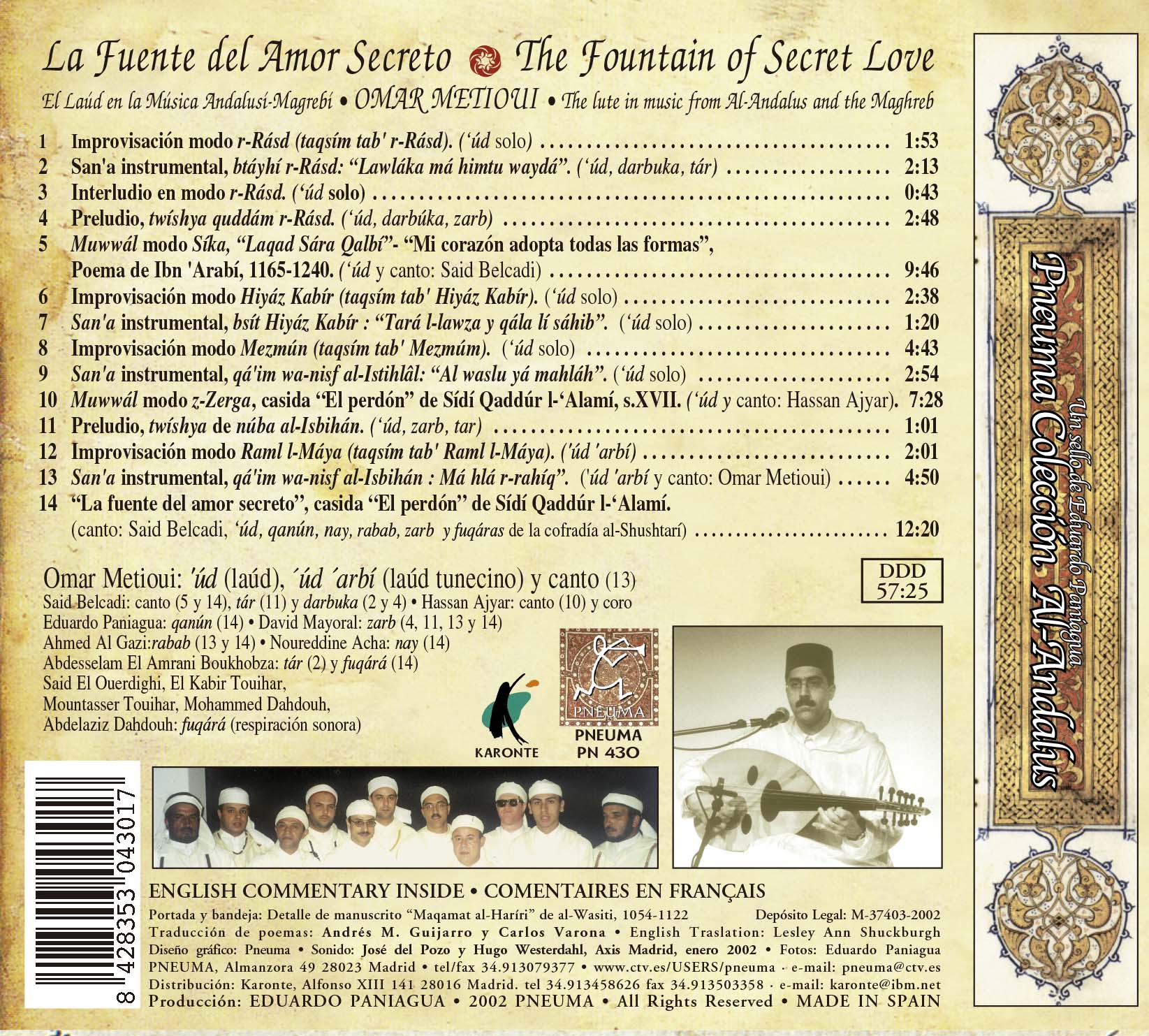

PN 430 LA FUENTE DEL AMOR SECRETO - THE FOUNTAIN OF SECRET LOVE El Laúd en la Música Andalusí-Magrebí

PN 430 LA FUENTE DEL AMOR SECRETO - THE FOUNTAIN OF SECRET LOVE El Laúd en la Música Andalusí-Magrebí

No se pudo cargar la disponibilidad de retiro

Índice

Índice

PN-430 LA FUENTE DEL AMOR SECRETO - THE FOUNTAIN OF SECRET LOVE

El Laúd en la Música Andalusí-Magrebí - The lute in music from Al-Andalus and the Maghreb

1 Improvisación modo r-Rásd (taqsím tab' r-Rásd). (‘úd solo) 1:53

2 San'a instrumental, btáyhí r-Rásd: “Lawláka má himtu waydá”. (‘úd, darbuka, tár) 2:13

3 Interludio en modo r-Rásd. (‘úd solo) 0:43

4 Preludio, twíshya quddám r-Rásd. (‘úd, darbúka, zarb) 2:48

5 Muwwál modo Síka, “Laqad Sára Qalbí”- “Mi corazón adopta todas las formas”,

Poema de Ibn 'Arabí, 1165-1240. (‘úd y canto: Said Belcadi) 9:46

6 Improvisación modo Hiyáz Kabír (taqsím tab' Hiyáz Kabír). (‘úd solo) 2:38

7 San'a instrumental, bsít Hiyáz Kabír: “Tará l-lawza y qála lí sáhib”. (‘úd solo) 1:20

8 Improvisación modo Mezmún (taqsím tab' Mezmúm). (‘úd solo) 4:43

9 San'a instrumental, qá'im wa-nisf al-Istihlâl: “Al waslu yá mahláh”. (‘úd solo) 2:54

10 Muwwál modo z-Zerga, casida “El perdón” de Sídí Qaddúr l-‘Alamí, s.XVII.

(‘úd y canto: Hassan Ajyar). 7:28

11 Preludio, twíshya de núba al-Isbihán. (‘úd, zarb, tar) 1:01

12 Improvisación modo Raml l-Máya (taqsím tab' Raml l-Máya). ('úd 'arbí) 2:01

13 San'a instrumental, qá'im wa-nisf al-Isbihán: Má hlá r-rahíq”.

('úd 'arbí y canto: Omar Metioui) 4:50

14 “La fuente del amor secreto”, casida “El perdón” de Sídí Qaddúr l-‘Alamí.

(canto: Said Belcadi, ‘úd, qanún, nay, rabab, zarb y fuqáras de cofradía al-Shushtarí) 12:20

Omar Metioui: 'úd (laúd), ´úd ´arbí (laúd tunecino) y canto (13)

Said Belcadi: canto (5 y 14), tár (11) y darbuka (2 y 4)

Hassan Ajyar: canto (10) y coro

Eduardo Paniagua: qanún (14)

David Mayoral: zarb (4, 11, 13 y 14)

Ahmed El Gazi: rabab (13 y 14)

Noureddine Acha: nay (14)

Abdesselam El Amrani Boukhobza: tár (2) y fuqárá (14)

Said El Ouerdighi, El Kabir Touihar, Mountasser Touihar, Mohammed Dahdouh, Abdelaziz Dahdouh: fuqárá (respiración sonora)

Portada y bandeja: Detalle de manuscrito “Maqamat al-Haríri” de al-Wasiti, 1054-1122

Traducción de poemas: Andrés M. Guijarro y Carlos Varona

Sonido: José del Pozo y Hugo Westerdahl, Axis Madrid, enero 2002 • Fotos: Eduardo Paniagua

Producción: EDUARDO PANIAGUA • 2002 PNEUMA

Descripción

Descripción

5 Muwwál modo Síka, Laqad Sára Qalbí, “Mi corazón adopta todas las formas”

Casida de Ibn 'Arabí, 1165-1240.

Mi corazón adopta todas las formas:

unos pastos para las gacelas y un monasterio para el monje.

(El) es templo para los ídolos, la Kaaba del peregrino,

las tablas de la Torá y el libro del Corán.

Sigo sólo la religión del amor, y hacia donde van sus jinetes me dirijo,

pues es el amor mi sola fe y religión.

Nuestro ideal es Bishr, el amante de Hind y de su hermana,

como lo es Qays y Lubna, Mayya y Gaylan.

Traducción: Carlos Varona

10 Muwwál modo z-Zerga, casida “El perdón” de Sídí Qaddúr l-‘Alamí, s.XVII.

No son míos la fuerza, los recursos, ni el poder;

Dueño no soy de mi destino:

De mi parte es sólo la súplica, de la Suya la aceptación.

Y el asunto no tiene vuelta de hoja.

Aquel que me dijo: ¡Sé paciente! y ¡abandónate a Mí!,

me libra de mi aflicción: Sólo suyo es el Poder.

Te juro que no recurrí a Tí,

hasta que tuve la certeza de Tú Poder infinito.

Traducción: Andrés M. Guijarro

13 San'a instrumental, qá'im wa-nisf al-Isbihán : Má hlá r-rahíq”.

Que dulce es el vino en tus pupilas.

Turba al enamorado y enciende los deseos.

Copero, escancia hábilmente al hermoso mientras pueda.

Ignora al censor, pues Dios es generoso y perdona a su siervo.

14 “La fuente del amor secreto”, casida “El perdón” de Sídí Qaddúr l-‘Alamí.

Cese en su aflicción y se regocije

aquel que conozca las penas de mi corazón,

pues mi sufrimiento ha llegado a su fin.

Ya no hay sitio en mi corazón para la tristeza:

He alcanzado la Unión que era mi objetivo.

Alabo al Señor del Cielo, me prosterno hacia la qibla

y digo: ¡Hoy he sido aceptado!.

Estaba sepultado en el sueño de la distracción,

pero he aquí que he despertado a la Alegría.

¿Quién temerá las palabras del envidioso o del espía?

Traducción: Andrés M. Guijarro

OMAR METIOUI

Nacido en Táger en 1962, estudia en el Conservatorio de su ciudad solfeo, música andalusí y laúd. En 1976 entra en la Orquesta de Música Andalusí de Tánger, siendo su primer laúd desde 1987 a 1994, bajo la dirección de Ahmed Zaitouni. En 1994 crea junto a Eduardo Paniagua el ensemble IBN BÁYA, grupo hispano-marroquí de música andalusí-magrebí. En 1995 realiza para el Centro de Documentación Musical de Andalucía en Granada la transcripción y transliteración de la Núba al-Istihlal. En 1997 funda el grupo de música sufí Al-Shushtarí y el ensemble Al-Ala Al-Andalusiyya. Ha dado conciertos en Europa, Asia (Japón e Irán) y en el mundo árabe. Desde 1991 es invitado a conferencias y congresos en España y Francia obteniendo numerosos premios.

HISTORIA DE DOS PUEBLOS

La música arábigo-andaluza es el resultado de la unión entre la música árabe proveniente de Oriente, la música afro-bereber del Magreb y la música practicada en la península Ibérica antes del año 711, fecha en la que Tariq Ibn Ziyád atravesó el estrecho de Gibraltar para conquistar España.

En efecto, esta región, mezcla de numerosas civilizaciones, dio lugar a una eclosión sin precedentes de un arte musical que conocerá un fulgurante desarrollo durante mas de ocho siglos tanto en Al-Andalus como en el Magreb. Después de la expulsión de los moriscos de España en 1609 y su éxodo masivo al Magreb, este arte perduró gracias al interés de los hispano-árabes. La música andalusí ha dejado impronta indeleble en el variado folklore y el imaginario popular español, entre otros influyendo en el nacimiento del cante tradicional andaluz llamado “flamenco”. Mientras tanto, el Magreb fue su único refugio, defensor y continuador de esta tradición musical hasta el presente.

HISTORIA RECIENTE DE UN INSTRUMENTO QUE HA REUNIDO A VARIOS PUEBLOS

El laúd, rey de los instrumentos del mundo árabe, continúa ocupando un lugar preferente en la tradición musical arábigo-andaluza. Instrumento base de la música culta, tuvo sus comienzos en los géneros populares.

En Oriente la importante evolución reciente del laúd es iniciada por el turco Muhyi d-Dín Haydar, maestro de los laudistas iraquíes de renombre internacional: Munir Bachir, su hermano Jamil muerto precozmente en 1977 y Salman Choukr. Con Munir Bachir el laúd fue elevado al rango de instrumento solista gracias al recital que ofreció en el Museo de Etnomusicología de Ginebra, bajo la invitación de Simón Jargy. La grabación de este concierto y su difusión en Europa tuvo un impacto decisivo para el futuro del laúd. Hoy en día, el iraquí Nassir Shamma ha tomado el relevo como maestro en Túnez y Egipto de nuevas técnicas del laúd. Respecto a esta escuela, que ha influido en gran parte de la tendencia actual, quisiera hacer alguna observaciones críticas. En primer lugar, la sonoridad del laúd ha sido modificada por los cambios realizados en el instrumento. Sin entrar en grandes detalles, el resultado de estas alteraciones acercan el timbre del laúd al de la guitarra. Por otro lado, el desarrollo de un “juego” vertical de las cuerdas que insisten en los acordes de terceras, quintas y octavas, así como el uso de cuerdas simultáneas y la adopción de repertorio clásico occidental, alejan al músico especialista del arte de la “modalidad” para encaminarle en el mundo sonoro de la “tonalidad”. La técnica del plectro en el ataque de las cuerdas (zand) se ha vuelto blando, dando un discurso musical menos acentuado, ininteligible, sin fuerza expresiva y que se pierde en la recitación.

En Turquía, durante siglos el laúd ha sido soslayado en beneficio del tanbur, instrumento de cuerdas metálicas y de mástil largo. Al principio del siglo XX aparecieron grandes virtuosos del laúd que revolucionaron la técnica de interpretación, como: Yorgo Bakanos, Cinucen Tonikorur y Ud Hrant.

En Irán algunas formaciones tímidamente comienzan de nuevo a integrar el laúd.

En Egipto intérpretes y compositores del siglo XX como Mohamed Kasabji, Mohamed Abdelouahab, Riad Senbati y Farid al-Atrache han tenido gran influencia sobre las masas populares árabes y se han impuesto como maestros absolutos del laúd, creando escuela. Farid al-Atrache arrancó exclamaciones de entusiasmo (Allah, Yá-lil, Ya-´ín) del pecho de cientos de espectadores en los momentos mágicos de sus fulminantes e innovadoras improvisaciones (taqásim).

En el estilo del laúd oriental, en Marruecos destaca en los años 60 el compositor y virtuoso Ahmad Al-Baydaoui.

Por otro lado Magreb tiene la particularidad de haber salvaguardado, gracias al proceso de la transmisión oral, un corpus clásico de música tradicional culta que tiene su origen en el siglo VII en la época de la islamización del Norte de África y de Al-Andalus.

Este edificio musical tendrá una evolución diferente a la de la música oriental, que ha sufrido la influencia de otras civilizaciones, concretamente la persa y la turca. Se pueden resumir brevemente la especificidad de la música arábigo-andaluza en los siguientes puntos: el desarrollo de un acercamiento místico a través del concepto del modo (tab’), el predominio del sistema diatónico, el canto según la núba y la preeminencia del ritmo musical sobre la métrica poética.

A decir verdad, en el Magreb actual asistimos a la coexistencia de dos tendencias divergentes. De una parte los adeptos del arte tradicional luchan por su preservación y difusión. Por otro lado, los innovadores apoyan el modelo de la escuela egipcia tratando de integrar en sus nuevas composiciones los elementos del lenguaje musical propio de su región.

En el repertorio de la música andalusí-magrebí los tradicionalistas continúan la práctica de laudes arábigo-andaluces como la kwítra de Argel y Tlemcen, el ´úd ´arbí de Túnez y Constantina, paralelamente al úd sharqí (oriental).

Virtuosos tradicionalistas como Khamis Tarnan de Túnez, o la familia Fergani de Constantina, en lo que concierne al ´úd ´arbí tunecino, maestro Bahhar de Argel por la kwítra, los maestros Ahmed Sháf´i y Mohamed Ben l-Arbi Temsamani de Marruecos por el úd sharqí tocado con estilo andalusí-magrebí, han pasado desapercibidos.

Así pues, en nuestros países del Magreb tenemos un urgente cometido; hace falta devolver al arte tradicional el lugar que le corresponde en nuestra sociedad ansiosa de modernidad. También es necesario cambiar la actitud de los músicos orientales, impermeables a la cultura musical del Occidente musulmán. Hoy día, a través del mundo, numerosos instrumentistas árabes, turcos y occidentales intentan ampliar las posibilidades del instrumento, tanto en el campo de la ejecución musical como en el su fabricación. Paralelamente reflexiones e investigaciones científicas comienzan a nacer tanto en Occidente como en los países musulmanes. Nos alegramos de esta apertura y esperamos ver que cada nación árabe da una personalidad original al laúd, ya que la riqueza está en la diversidad.

EL ARTE DE LA IMPROVISACIÓN

La improvisación, a mi entender, es para la música el equivalente a lo que la poesía tiene frente a la prosa. Es una forma condensada de expresar las ideas. Requiere evitar un discurso reiterativo y crear constantemente un efecto sorpresa. La improvisación da nueva vida a una obra sin llegar a destruirla. Es una técnica que se adquiere gracias a los métodos tradicionales de enseñanza. En efecto, desde el primer contacto con la música, el aprendiz debe impregnarse del canto, el ritmo y la técnica instrumental para poder desarrollar una memoria multidireccional. Sobre todo no debe proceder a la parcelación de las materias musicales propiciadas por los métodos clásicos occidentales. No se debe olvidar someter el arte de la improvisación a esquemas y reglas impuestas por las características del modo musical (tab’), ligadas a la escala modal con sus intervalos propios y a la influencia psicofisiológica que tiene sobre el espíritu humano.

Todo esto se consigue, a partir de los elementos citados, respetando con rigor las reglas y la estética establecida por la tradición, creando esta atmósfera específica del modo (tab’/ maqám). Esta clave permite diferenciar un trabajo fiel a la legítima tradición de entre las múltiples tendencias de la moda, que quieren escapar a toda regla para hacer fácil el duro aprendizaje, dando libre curso a sus fantasías. En este último caso, la improvisación se transforma en anarquía. La música es un arte noble, profundo y sublime. No debe sembrar el desorden sino que debe ayudarnos a encontrar el equilibrio y elevar nuestra alma y espíritu. Lo contrario deviene en perversión.

COMENTARIOS AL PROGRAMA

1 Improvisación modo r-Rásd (taqsím tab' r-Rásd). (‘ûd solo)

El modo Rásd es el que corresponde a la núba Rásd en el repertorio al-ála de Marruecos. Tiene una estructura casi pentatónica que le confiere un carácter gnáwí (cofradía religiosa de origen africano que posee un repertorio musical propio). Mas al Este de Túnez, debido a su origen afro-bereber se denomina rásd ´abidí, es decir, “rásd de los esclavos”. En este modo basado sobre la nota (re) destacan los intervalos de tercera (fa sostenido) y de sexta (si) de la escala, provocando una sensación intensa que genera energía positiva y que incita a la acción.

2 San'a instrumental, btáyhí r-Rásd: “Lawláka má himtu waydá”. (‘ûd, drbûga, târ)

La melodía de esta canción pertenece al tercer movimiento de la núba Rásd que se sustenta en la última fase del ritmo btáyhi (4/4). Incita a la danza y a la alegría.

3 Interludio en modo r-Rásd. (‘ûd solo)

Esta obra sencillamente intenta restablecer la atmósfera del modo con el fin de enlazar la anterior con la siguiente.

4 Preludio, twíshya quddám r-Rásd. (‘ûd, drbúga, zarb)

Gracias a la flexibilidad que permite el ritmo quddám (3/4) en su fase lenta, cada nueva ejecución de esta obra, aparentemente sencilla, constituye una ocasión de reencuentro con el espíritu de la música arábigo-andaluza.

5 Muwwál modo Síka, “Laqad Sára Qalbí”- “Mi corazón adopta todas las formas”, Poema de Ibn 'Arabí, 1165-1240. (‘ûd y canto: Said Belcadi)

Con la voz se abren nuevos horizontes en el mundo de la improvisación de la música andalusí. El modo Síka (mi) expresa la nostalgia de la separación. Es un modo muy propio de la expresión de la música andaluza llamada flamenco. El poema cantado es del andaluz del siglo XII Muhyi d-Din Ibn ´Arabí, apodado el “maestro supremo”. Uno de los mas grandes místicos de todos los tiempos.

6 Improvisación modo Hiyáz Kabír (taqsím tab' Hiyáz Kabír). (‘ûd solo)

Este modo tiene el (re) como nota básica y tiene su propia núba en el repertorio al-ála. Su escala es interesante tiene personalidad propia debido a la forma conclusiva descendente sobre una segunda aumentada.

7 San'a instrumental, bsít Hiyáz Kabír: “Tará l-lawza y qála lí sáhib”. (‘ûd solo)

Consta de dos melodías pertenecientes a la parte final (insiraf) del primer ritmo de la núba y nos evoca a danzas medievales.

8 Improvisación modo Mezmún (taqsím tab' Mezmúm). (‘ûd solo)

Este modo expresa sentimientos de valentía y honestidad. Sobre la nota (do) es pionero en introducir el juego que tiende a la verticalidad de las notas (acordes) e introduce particular acento en los intervalos de tercera, quinta y octava.

9 San'a instrumental, qá'im wa-nisf al-Istihlâl: “Al waslu yá mahláh”. (‘ûd solo)

Esta obra me acompaña siempre en mis ensoñaciones y pensamientos. Me fascina por su sencillez y por la multitud de facetas que permite imaginar sin dejar de redescubrir su trama melódica. Su ritmo qá´im wa-nisf (8/4) es especialmente rico respecto al reparto de la acentuación en los compases de medida (dawr) y tiene un efecto sorpresa al agrupar los tiempos fuertes en el final de la secuencia rítmica.

10 Muwwál modo z-Zerga, casida “El perdón” de Sídí Qaddúr l-‘Alamí, s.XVII. (‘ûd y canto: Hassan Ajyar)

Este modo conduce las inflexiones del alma en el sometimiento de sus deseos. Es empleado especialmente en el repertorio malhun (canto popular de las corporaciones artesanales que se basa en la poesía dialectal) y también en el canto de las cofradías religiosas (záwya).

11 Preludio, twíshya de nûba al-Isbihán. (‘ûd, zarb, tar)

En esta obra empleo un laúd afinado un tono mas alto. El instrumento usado anteriormente tiene un diapasón afinado un tono y medio mas alto. El grado de las notas a las que se hace referencia en este texto es según el diapasón y no respecto a la afinación utilizada en la grabación. La twíshya está en el modo Isbihán (re) que también tiene una núba propia en el célebre cancionero marroquí de al-Ha´ik (hacia 1800). Se llama twíshya de la núba porque puede ser utilizada como inicio de cualquiera de las cinco fases rítmicas de la misma.

12 Improvisación modo Raml l-Máya (taqsím tab' Raml l-Máya). ('úd 'arbí)

Utilizo en esta improvisación el ´ud ´arbi, laúd árabe tunecino. Tiene solo cuatro cuerdas dobles con afinación especial en “quintas abrazadas”, una dimensión que da un intervalo de sexta en el punto de intersección del mástil con la tabla armónica, cuerdas de tripa y para tocarlo se usa plectro de pluma de águila. Este instrumento andalusí-magrebí nos introduce en una atmósfera, una estética y una dinámica muy diferente a la del laúd oriental (úd sharqi), utilizado hasta ahora.

13 San'a instrumental, qá'im wa-nisf al-Isbihán : Má hlá r-rahíq”. ('úd 'arbí y canto: Omar Metioui)

Esta canción, que Eduardo Paniagua me ha incitado a cantar a solo, tiene una sencilla melodía pero que requiere especial sensibilidad para su interpretación. Mi maestro Múláy Ahmed Lúqili (1909-1989) gozaba de una remarcable voz poseedora de las cualidades que debe tener el canto tradicional según la sabiduría oriental. Eligiendo esta obra quiero rendirle homenaje; que Dios le tenga en su gloria.

14 “La fuente del amor secreto”, casida “El perdón” de Sídí Qaddúr l-‘Alamí. (canto: Said Belcadi, ‘ûd, qanún, nay, rabab, zarb y fuqáras de la cofradía al-Shushtarí)

De esta fuente brota un vino que simboliza al Amor. En tanto que fluya existe la esperanza de la Unión. Con la respiración sonora el pecho de los derviches (fuqára) se desgarra y expresa los gemidos profundos que dejan aplastado al que escucha atentamente bajo la presión del Único. Nadie puede detener esta respiración del alma. El único medio para poder soportar esta prueba es llegar al estadio supremo del éxtasis. Ello requiere salir de si mismo para poder llegar a la Unión. El laúd, igual que la voz, ayuda al faqir, que saborea el mensaje hermeneutico de las palabras de los grandes místicos, a realizar una ascensión progresiva sobre lo material. Es necesario beber de esta fuente para trascender la verdad divina.

OMAR METIOUI. Traducción: Eduardo Paniagua

english

Born in Tangier in 1962, Omar Metioui studied musical theory, Andalusí music and lute at the Conservatory in his hometown. In 1976 he joined the Tangier Orchestra of Andalusí Music and was first lute from 1987 to 1994, under the musical direction of Ahmed Zaitouni. In 1994 he founded the ensemble IBN BÁYA together with Eduardo Paniagua, a Hispano-Moroccan group playing Andalusí-Maghrebi music. In 1995 he completed the transcription and transliteration of the Núba al-Istihlal for the Centre of Musical Documentation of Andalucía in Granada. In 1997 he founded Al-Shushtarí, a Sufi music group and the ensemble Al-Ala Al-Andalusiyya. He has given concerts in Europe, Asia (Japan and Iran) and in the Arab world. Since 1991 he has been invited to conferences and congresses in Spain and France and won several awards.

français

Né à Tanger en 1962. Etudie au Conservatoire de Tanger le solfège, la musique andalouse et le luth. En 1976, il rejoint l'orchestre de musique andalouse de Tanger. De 1987-1994, il est le Premier luthiste de l'Orchestre du Conservatoire de Tanger dirigé par maître Ahmed Zaitouni. En 1994, il crée, l’ensemble IBN BÁYA, un groupe hispano-marocain de musique andalou-maghrébine, avec Eduardo Paniagua. En 1995, chargé par le Centre de Documentation Musicale de L’Andalousie de Grenade, il entreprend la transcription et la translittération de nûba al-Istihlâl. En 1997, il fonde le groupe de musique soufi, AL-SHUSHTARI, et l’ensemble AL-ALA Al-ANDALUSIYYA. Il donne des concerts en Europe, en Asie (Japon, Iran) et dans le monde arabe. De 1991 à 2002, il donne des conférences, notamment en Espagne et en France, et obtient de nombreux prix.

ENGLISH

A HISTORY OF TWO PEOPLES.

Islamic-Andalusian music is the result of the fusion of Islamic music from the Orient, Berber music from North Africa, and music played in the Iberian Peninsula before the year 711, when Tariq Ibn Ziyád crossed the straits of Gibraltar to conquer Spain.

This region, with its blend of different civilisations, hatched a musical art that was to undergo an extraordinary development over more than eight centuries in Al-Andalus and in North Africa. After the expulsion of the Moriscos from Spain in 1609 and their massive exodus to North Africa, this art form was kept alive by the Hispano-Arabs. Andalusí music left an indelible mark on Spanish popular folklore and creativity, most noticeably appreciated perhaps in traditional Andalusian “flamenco”. It was in the Maghreb, however, that the Andalusí musical tradition was to find refuge, where it has been defended and perpetuated until now.

RECENT HISTORY OF AN INSTRUMENT THAT HAS UNITED SEVERAL PEOPLES

The lute, king of all instruments in the Arab world, continues to occupy a place of preference in the Islamic-Andalusian musical tradition. It is the fundamental instrument in classical music, and began in the popular genres.

In the Orient the important recent evolution of the lute was started by Muhyi d-Dín Haydar, from Turkey, master of Iraqi lutenists of international renown: Munir Bachir, his brother Jamil, who met an early death in 1977, and Salman Choukr. Munir Bachir elevated the lute to the heights of a solo instrument after the recital given in the Museum of Ethnomusicology in Geneva, on the invitation of Simón Jargy. The recording of this concert and its distribution in Europe played a decisive role in the future of the lute. Today, the Iraqi Nassir Shamma has taken over as master of new lute techniques in Tunisia and Egypt. This school has had great influence on current trends and I would like to make some observations. Firstly, the sound of the lute has been modified by the changes made to the instrument. Without going into great detail, these alterations have resulted in the timbre of the lute becoming more like that of the guitar. Also, the vertical use of the strings producing chords mainly in thirds, fifths and octaves, the simultaneous use of strings and the adoption of a western classical repertoire, distance the specialist musician from the art of “modality” in the approach to the world of “tonality”. The plectrum technique to attack the strings (zand) has become soft, weakening the accent in the musical discourse, often rendering the music meaningless and without expressive force.

In Turkey the lute has been overshadowed by the “tanbur” for centuries, an instrument with metal strings and a long neck. At the beginning of the 20th century great lute virtuosos appeared who revolutionised performance technique, such as Yorgo Bakanos, Cinucen Tonikorur and Ud Hrant. In Iran some groups began a timid integration of the lute.

In Egypt 20th century performers and composers such as Mohamed Kasabji, Mohamed Abdelouahab, Riad Senbati and Farid al-Atrache have had a great influence on the popular Arab masses and have become absolute masters of the lute, creating a following. Farid al-Atrache drew exclamations of enthusiasm (Allah, Yá-lil, Ya-’ín) from hundreds of spectators at magic moments of his brilliant and innovatory improvisations (taqásim).

Ahmad Al-Baydaoui was an important composer and virtuoso of the oriental style in Morocco in the 60s.

Yet, on the other hand, the Maghreb can boast having safeguarded a classical corpus of cultured traditional music that originated in the 7th century when North Africa and Al-Andalus were undergoing a process of Islamization, thanks to word of mouth.

The evolution of this musical edifice was to differ considerably from the music emerging from the Orient, which was influenced by other civilisations, namely the Persian and Turkish. The essential characteristics of Islamic-Andalusian music can be summarised briefly in the following points: the development of a mystic approximation through the concept of the mode (tab), the predominance of the diatonic system, chant according to the núba and the pre-eminence of musical rhythm over poetic metre.

The truth is that in present day North Africa we are witnessing the co-existence of two divergent trends. On the one hand the adepts of the traditional art are fighting for its conservation and divulgence. On the other hand, the innovators support the Egyptian school model and make the effort to integrate elements of musical language that are native to their region in new compositions.

In the Andalusí-Maghrebí repertoire the traditionalists continue to use Islamic-Andalusian lutes such as the kwítra from Algeria and Tlemcen, the ‘úd ‘arbí from Tunisia and Constantine, in parallel with the úd sharqí (oriental).

Traditionalist virtuosos such as Khamis Tarnan from Tunisia, or the Fergani family from Constantine, continue to use the Tunisian ‘úd ‘arbí, while master Bahhar from Algiers prefers the kwítra, and the masters Ahmed Sháf’i and Mohammed ben l-Arbi Temsamani favour the úd sharqí played in the Andalusí-Maghrebí style. They tend however to go unnoticed.

Thus, in our countries of the Maghreb it is imperative that we return traditional art to its rightful place in our society. A society that accepts modernity only too easily. It is also necessary to change the attitude of the Oriental musicians, impervious to the musical culture of the Muslim West. Today numerous Islamic, Turkish and Western experts throughout the world attempt to expand the possibilities of the lute both in the way it is exploited musically and in its manufacture. Ideas and scientific research start to emerge in parallel both in the West and in Muslim countries. We are happy about this development and hope to see that each Arab nation lends its own personality to the lute, since variety is the spice of life.

THE ART OF IMPROVISATION

Improvisation, to my mind, is to music as poetry is to prose. It is a condensed form of expressing ideas. Reiterative discourse should be avoided and an element of surprise constantly created. Improvisation gives new life to a work without destroying it. It is a technique that can be acquired thanks to the traditional methods of teaching. From the first contact with music, the apprentice must imbibe chant, rhythm and instrumental technique in order to be able to develop a multidirectional memory. Above all he must not adopt the system of parcelling music into different categories as classical western methods do. The art of improvisation must still follow the schemes and rules imposed by the characteristics of the musical mode (tab’), linked to the modal scale with its own intervals and the psycho-physiological influence on the human spirit.

All this can be achieved if these elements are present and the rules and aesthetics established by the tradition are rigorously adhered to, creating the appropriate atmosphere for the mode (tab’/maqám). This is the key to identifying a work that is loyal to the legitimate tradition among diverse fashionable trends that want to escape from the rules to make the difficult learning process easy, and give free reign to fantasy. Improvisation in this case becomes anarchy. Music is a noble art, profound and sublime. It should not sow disorder but should help us to reap equilibrium and lift up our soul and spirit. The contrary becomes a perversion.

COMMENTS ON THE PROGRAMME

1.Improvisation in the r-Rásd (taqsím tab' r-Rásd) mode. (‘ûd solo)

The Rásd mode corresponds to the Rásd núba in the al-ála repertoire from Morocco. It has an almost pentatonic structure reminiscent of the characteristics of the gnáwí (religious order of African origin that has its own musical repertoire). Further to the east of Tunisia it is known as rásd´abídí, that is, “rásd of the slaves” after its Afro-Berber origin. The keynote of this mode is D and it favours intervals of a third (F sharp) and a sixth (B), which bring an intensity to the piece that generates positive energy and action.

2 Instrumental San'a, btáyhí r-Rásd: “Lawláka má himtu waydá”. (‘ûd, drbûga, târ)

This melody is from the third movement of the Rásd núba in the last phase of the btáyhi rhythm (4/4). It is a happy piece of dance music.

3 Interlude in the r-Rásd mode. (‘ûd solo)

This piece simply attempts to re-establish the atmosphere of the mode in order to link the previous tune to the next.

4 Prelude, twíshya quddám r-Rásd.

(‘ûd, drbúga, zarb)

The flexibility of the quddám rhythm (3/4) in its slow phase reflects the spirit of Islamic-Andalusian music in this apparently simple work each time it is played.

5 Muwwál Síka mode, “Laqad Sára Qalbí”- “My heart adopts all forms”, Poem by Ibn 'Arabí, 1165-1240. (‘ûd and chant: Said Belcadi)

With the voice new horizons open in the world of improvisation of Andalusí music. The Síka mode (E) expresses the nostalgia of separation. It is a mode that is very typical in Andalusian flamenco. The poem chanted is by the 12th century Andalusian Muhyi d-Din Ibn ‘Arabí, known as the “supreme master”, one of the great mystics of all time.

6 Improvisation in the Hiyáz Kabír mode (taqsím tab' Hiyáz Kabír). (‘ûd solo)

This mode is based on D and has its own núba in the al-ála repertoire. Its scale is interesting and unique in that it descends to a close on an augmented second.

7 Instrumental San'a, bsít Hiyáz Kabír : “Tará l-lawza y qála lí sáhib”. (‘ûd solo)

This piece consists of two melodies belonging to the final part (insiraf) of the first rhythm of the núba and evokes medieval dances.

8 Improvisation in the Mezmún mode (taqsím tab' Mezmúm). (‘ûd solo)

This mode expresses feelings of valour and honesty. The keynote is C and it is a forerunner in the vertical expression of notes (chords), thirds, fifths and octaves being prominent.

9 Instrumental San'a, qá'im wa-nisf al-Istihlâl: “Al waslu yá mahláh”. (‘ûd solo)

This work is always with me in my dreams and thoughts. It fascinates me in its simplicity and multitude of aspects that give free rein to imagination without obstructing the rediscovery of the melodic system. Its rhythm qá’im wa-nisf (8/4) is especially rich because of the distribution of accent in the bars (dawr) and it has a surprise effect by grouping the strong beats at the end of the rhythmic sequence.

10 Muwwál mode z-Zerga, qasida “The Pardon” by Sídí Qaddúr l-‘Alamí, s.XVII. (‘ûd chant: Hassan Ajyar)

This mode leads the soul to bow before its desires. It is used especially in the malhun repertoire (popular chant of the craftsmen’s guilds based on poetry in dialect) and also in the chant of the religious brotherhoods (záwya).

11 Prelude, twíshya de nûba al-Isbihán.

(‘ûd, zarb, tar)

In this work I tune the lute a tone higher. The lute used formerly was tuned a tone and a half higher. The range of the notes mentioned in the text refers to the old range and not the tuning used on this recording. The twíshya is in the Isbihán (D) mode which also has its own núba in the famous Moroccan songbook of al-Ha’ik (about 1800). It is called twíshya of the núba because it can be used as the beginning of any of the five rhythmic phases.

12 Improvisation in the Raml l-Máya (taqsím tab' Raml l-Máya) mode. ('úd 'arbí)

In this improvisation I use the ‘ud ‘arbí, Arab lute from Tunisia. It has only four pairs of strings tuned in “embraced fifths”, a dimension that gives an interval of a sixth at the point where the neck meets the soundboard. The strings are made of gut and to play it I use an eagle quill plectrum. This Andalusi-Maghrebi instrument creates a very different atmosphere compared to the oriental lute (úd sharqi), used until now.

13 Instrumental San'a, qá'im wa-nisf al-Isbihán : Má hlá r-rahíq”. ('úd 'arbí and chant: Omar Metioui)

This song, which Eduardo Paniagua convinced me to sing as a solo, has a simple melody but to sing it well requires special sensibility. My master Múláy Ahmed Lúqili (1909-1989) had a remarkable voice with all the qualities that traditional chant should have according to oriental wisdom. By choosing this work I would like to pay him a tribute; may God keep him in His glory.

14 “The Fountain of Secret Love”, qasida “The Pardon” by Sídí Qaddúr l-‘Alamí. (chant: Said Belcadi, ‘ûd, qanún, nay, rabab, zarb and fuqáras of the al-Shushtarí brotherhood)

From this fountain flows a wine that symbolises Love. As long as it flows the hope of Union exists. The audible breathing of the dervishes (fuqára) reaches a point where it seems to rip open their chests and the engrossed listener is overwhelmed by their deep sighs, under the pressure of the One. Nobody can stop this breathing that comes from the soul. The only way to be able to bear it is to reach the supreme state of ecstasy. That means that one must leave one’s body to attain Union. The fakir, who savours the hermeneutic message of the words of the great mystics, is helped by the lute, as well as the voice, in his quest to achieve a progressive ascension over material things. It is essential to drink from this fountain in order to transcend the divine truth.

OMAR METIOUI

Traslation: Lesley Ann Shuckburgh

Compartir

-

Envío gratis en pedidos mayores a 50 €.

Entrega en 5-7 días laborables para pedidos en España, en el caso de envíos fuera de España el tiempo de envío podría ser algo mayor.

-

Todo el trabajo de Pneuma Music se ha realizado en España.

Música medieval española inédita hasta el momento. Sus discos, con formato Digipack de cubierta de cartón y libreto interior (bilingüe + idioma original), quieren acercarse a una obra de arte total.