pneumamusic

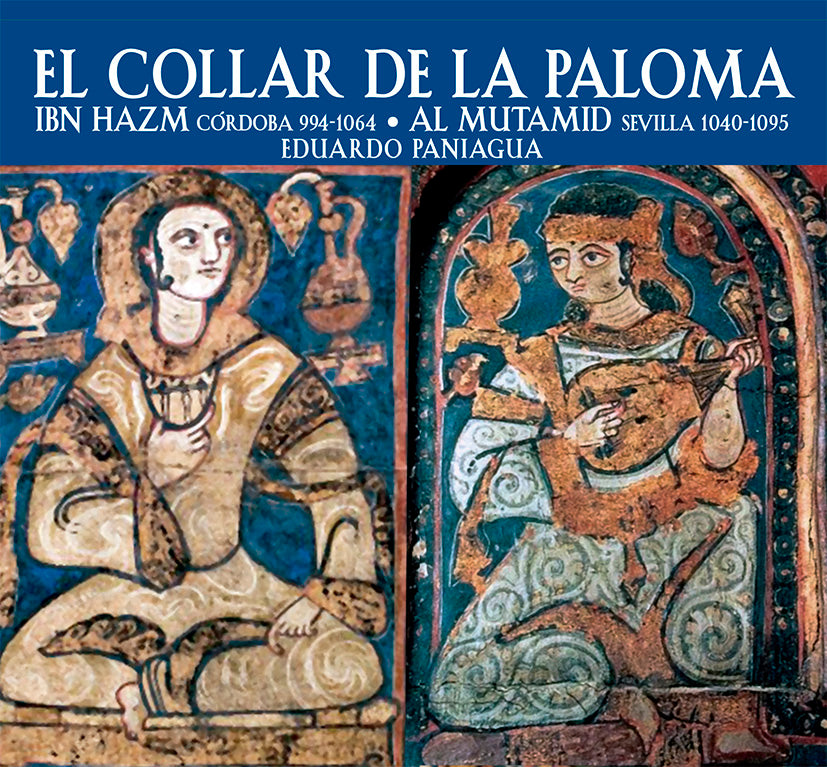

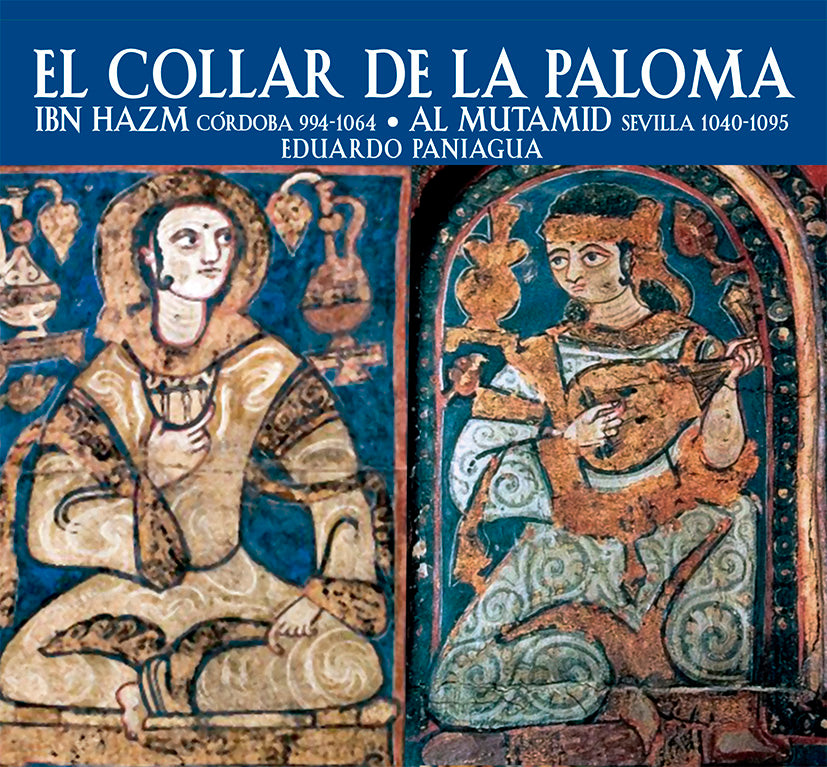

PN 1660 EL COLLAR DE LA PALOMA. IBN HAZM, CORDOBA 994-1064-AL MUTAMID, SEVILLA 1040-1095

PN 1660 EL COLLAR DE LA PALOMA. IBN HAZM, CORDOBA 994-1064-AL MUTAMID, SEVILLA 1040-1095

No se pudo cargar la disponibilidad de retiro

Índice

Índice

IBN HAZM CÓRDOBA 994-1064 • AL MUTAMID SEVILLA 1040-1095

Eduardo Paniagua

El collar de la tórtola y la sombra de la nube. Dialogo en Silves de Ibn Hazm de

Córdoba 994-1064 Al Mutamid de Sevilla 1040-1095.

Los poemas de Ibn Hazm son adaptaciones de Eduardo Paniagua sobre las

traducciones de Emilio García Gómez (1905-1995) y de Jaime Sánchez Ratia. Las de

Al Mutamid son adaptaciones sobre las traducciones de Juan Varela (1824-1905) y de

Emilio García Gómez. Las melodías son arreglos de Eduardo Paniagua sobre música

de la tradición andalusí de Marruecos y Túnez, así como cantigas y cantos

tradicionales andaluces y extremeños.

THE DOVE'S NECKLACE

The turtledove’s necklace and the shadow of the cloud. Dialogue in Silves between Ibn

Hazm of Córdoba 994-1064 and Al Mutamid of Seville 1040-1095.

Eduardo Paniagua has adapted Ibn Hazm’s poems from translations by Emilio García

Gómez (1905-1995) and Jaime Sánchez Ratia. Al Mutamid’s poems have been

adapted from translations by Juan Varela (1824-1905) and Emilio García Gómez. The

melodies are arrangements by Eduardo Paniagua based on music from the Andalusi

tradition of Morocco and Tunisia, and on cantigas and traditional songs from Andalusia

and Extremadura.

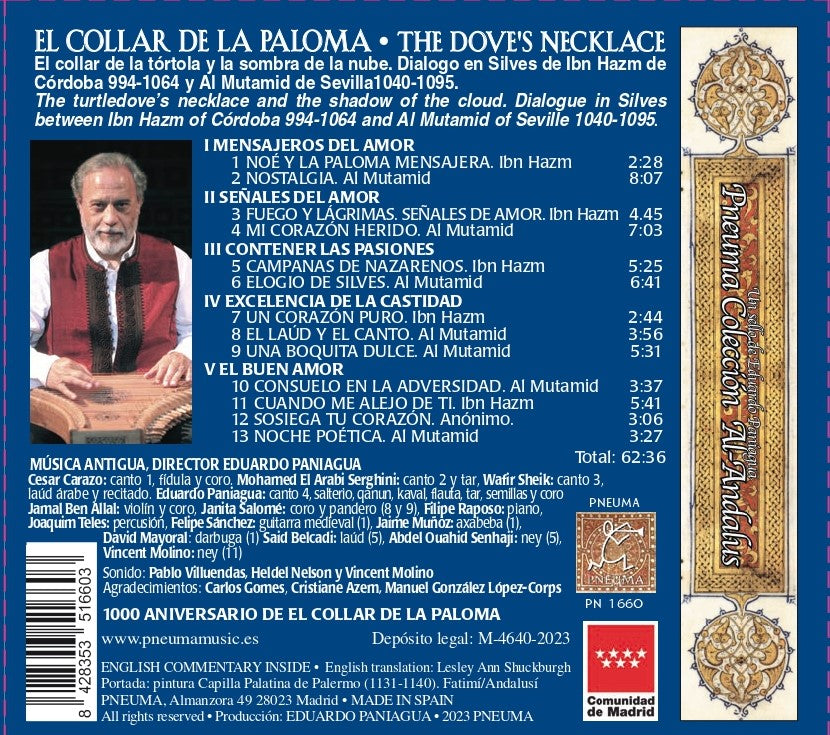

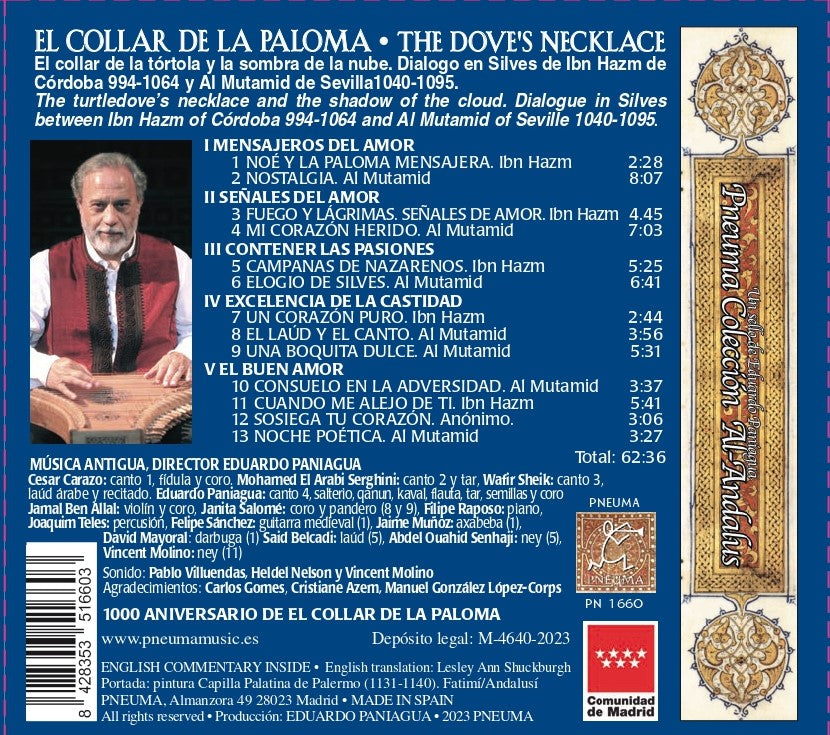

MENSAJEROS DEL AMOR

1 NOÉ Y LA PALOMA MENSAJERA. Ibn Hazm 2:28

2 NOSTALGIA. Al Mutamid 8:07

II SEÑALES DEL AMOR

3 FUEGO Y LÁGRIMAS. SEÑALES DE AMOR. Ibn Hazm 4.45

4 MI CORAZÓN HERIDO. Al Mutamid 7:03

III CONTENER LAS PASIONES

5 CAMPANAS DE NAZARENOS. Ibn Hazm 5:25

6 ELOGIO DE SILVES. Al Mutamid 6:41

IV EXCELENCIA DE LA CASTIDAD

7 UN CORAZÓN PURO. Ibn Hazm 2:44

8 EL LAÚD Y EL CANTO. Al Mutamid 3:56

9 UNA BOQUITA DULCE. Al Mutamid 5:31

V EL BUEN AMOR

10 CONSUELO EN LA ADVERSIDAD. Al Mutamid 3:37

11 CUANDO ME ALEJO DE TI. Ibn Hazm 5:41

12 SOSIEGA TU CORAZÓN. Anónimo 3:06

13 NOCHE POÉTICA. Al Mutamid 3:27

Total: 62:36

Música Antigua, director Eduardo Paniagua

Cesar Carazo: canto 1, fídula y coro.

Mohamed El Arabi Serghini: canto 2 y tar,

Wafir Sheik: canto 3, laúd árabe y recitado

Eduardo Paniagua: canto 4, salterio, qanun, kaval, flauta, tar, semillas, darbuga y coro

Jamal Ben Allal: violín y coro,

Janita Salomé: coro y pandero (8 y 9),

Filipe Raposo: piano,

Joaquim Teles: percusión,

Felipe Sánchez: guitarra medieval (1),

Jaime Muñoz: axabeba (1),

David Mayoral: darbuga (1)

Said Belcadi: laúd (5),

Abdel Ouahid Senhaji: ney (5),

Vincent Molino: ney (11)

Sonido: Pablo Villuendas, Heldel Nelson y Vincent Molino

Agradecimientos: Carlos Gomes (Transiberia), Cristiane Azem, Manuel González

López-Corps

Descripción

Descripción

IBN HAZM CÓRDOBA 994-1064 • AL MUTAMID SEVILLA 1040-1095

Eduardo Paniagua

Ibn Hazm

Abu Muḥammad ʿAli ibn Aḥmad ibn Saʿīd ibn Ḥazm, llamado entre los cristianos Abén Házam

(Córdoba 994 - Montíjar, Huelva 1064), fue un filósofo, teólogo, historiador, narrador y poeta

andalusí, considerado el “Padre de la Religión comparada”. Sus antepasados fueron hispanos

cristianos convertidos al islam, muladíes. Nació en los últimos años del siglo X antes de la crisis

del Califato de Córdoba. Su abuelo se trasladó a la capital califal y su padre, Ahmad, fue visir de

Almanzor. Ali pasó su educación en la corte cordobesa del palacio al-Zahira. Como miembro de la

aristocracia, vivió la guerra civil cordobesa en el bando Omeya, en contra del nuevo linaje amirí de

Almanzor. Muerto en 1012 su padre Ahmad, Ali fue desterrado en Almería a los 18 años. Desde

allí apoyó a un nuevo pretendiente Omeya al Califato, y en la Granada zirí Ibn Hazm fue hecho

prisionero. De ahí se retiró a Játiva, donde a sus 28 años en 1022, escribió, a instancias de su

amigo Muhammad Ibn Ishaq, el libro que ahora cumple mil años, El collar de la paloma.

En 1023 Córdoba eligió al nuevo Califa Abderramán V, que le nombró visir, pero su gobierno duró

un mes y tras la ejecución del Califa Ibn Hazm fue de nuevo encarcelado. Ali renunció a la política

para dedicarse a los estudios jurídicos y teológicos de la escuela zahirí, de la que daba cursos

junto a su maestro Abū-l-Jiyār de Santarén en la Mezquita de Córdoba, hasta que en 1027 fue

denunciado por contravenir la oficial escuela malikí. Desencantado de la política y la enseñanza

abandonó la vida pública y se dedicó a visitar los distintos reinos de taifas como polemista y

erudito. En 1039 tras refugiarse en Mallorca, mantuvo disputas con sabios y reyes como al-

Mutadid de Sevilla, padre de al-Mutamid. Las controversias produjeron la dramática quema de sus

libros. Esto inspiró a Ibn Hazm sus famosos versos: “Dejad de prender fuego a pergaminos y

papeles, y mostrad vuestra ciencia para que se vea quien es el que sabe. Aunque queméis el

papel nunca quemaréis lo que contiene, puesto que en mi interior lo llevo, viaja siempre conmigo

cuando cabalgo, conmigo duerme cuando descanso, y en mi tumba será enterrado”. (Traducción

de José Miguel Puerta Vílchez). Mantuvo esta vida de sabio errante hasta el final de sus días

cuando, exiliado por Al- Mutadid, se retiró con sus hijos al cortijo familiar de Montíjar.

Obra: Fue un ingente polígrafo de miles de páginas. Escribió obras históricas, como “Epístola en

elogio de al-Ándalus”, “Bordado de la novia”, “Linajes árabes” y la más importante, “Historia crítica

de las religiones, sectas y escuelas”, en la que traza los rasgos de los sistemas filosóficos

contrarios a las religiones, incluidas las anti islámicas, y es el primer tratado de historia comparada

de las religiones escrito en idioma alguno. De carácter didáctico es “Los caracteres y la conducta”

y “Polémica teológica con Ibn Nagrella” poeta judío, jefe del ejército y visir del reino de Granada

(1035-1066). También escribió numerosas obras filosóficas, basando su pensamiento en

Aristóteles. Al relacionar las verdades con la teología se acerca y antecede los postulados de

Santo Tomás. Merece mención su obra titulada “Epístola sobre la licitud o ilicitud del canto y la

música instrumental”, donde compara las posturas de las escuelas de jurisprudencia islámica y los

posicionamientos de los alfaquíes orientales y andalusíes sobre la aceptación o el rechazo hacia

la música y la compraventa de esclavas cantoras muy cualificadas (al-qiyan), mujeres que eran

reconocidas por su esmerada educación. Argumentos que le llevan a posicionarse a favor de la

disciplina musical, incluyendo a la música entre las ciencias del quadrivium pitagórico, junto a la

Aritmética, la Geometría y la Astronomía.

Su obra más famosa es Ṭawq al-ḥamāma o El collar de la paloma, una joya literaria en prosa y

primer tratado conocido sobre el amor y los amantes. El libro en realidad tiene este título “El collar

de la tórtola y la sombra de la nube”. Este título largo es muy sugerente por combinar símbolos

opuestos de lo efímero y pasajero con lo profundo y espiritual en el lenguaje semítico. El aro de

plumas coloridas en el cuello de la tórtola como condecoración divina de pasajero amor carnal, el

prestigio de la paloma en su servicio mensajero a Noé en su Arca del diluvio y su figura como el

Espíritu Santo en el bautismo de Jesucristo en el Jordán. La sombra de la nube como algo efímero

que pasa raudo, como la vida o algún tipo de amor, o como la sombra divina de la nube que

acompañó al pueblo elegido en el desierto. Más sugerente aún es el título en el idioma andalusí,

pues se trata de un sutil pareado “Tawq al-hamáma wa-zill al-gamáma”, que literalmente viene a

decir: llevo tu íntima amistad con la misma honra con la que la tórtola lleva a gala su aro de

plumas.

Es un libro de reflexiones sobre la verdadera esencia del amor, intentando descubrir lo que tiene

de común e inmutable a través de los siglos y las civilizaciones. De influencia neoplatónica, Ibn

Ḥazm incluye el "amor udrí", adhiriéndose a la corriente literaria y estética de los Banū ‘Uḏra o

“Hijos de la Pureza” de Bagdad, introducida en la península por el astrónomo Maslama al Mayriti

(Madrid c. 950- Córdoba c. 1007), citado en “el collar”. Constituye también un diwan, o antología

poética de tema amoroso, pues contiene sus elegantes y refinadas poesías con detalles

autobiográficos. Ibn Hazm es un hombre de profundas convicciones religiosas y dirigió parte de

sus críticas a la relajación de costumbres en Al-Ándalus. El libro desarrolla una forma de concebir

la belleza, el amor y la literatura de una manera exquisita, en la que se mezcla neoplatonismo y

estoicismo. Partiendo de que el alma es bella y busca la belleza surge el amor, que si es

verdadero es eterno. El amor que se queda en la belleza física es el amor carnal, que tiene para él

poco valor: “Te amo con un amor inalterable, mientras tantos amores humanos no son más que

espejismos. Te consagro un amor puro y sin mácula: en mis entrañas está visiblemente grabado y

escrito tu cariño.”

El libro, que terminaba en 28 capítulos, los días del mes, las letras del alifato, tiene añadidos dos

capítulos más en los que se aportan muchos datos, fechas y contenidos teológicos sobre la

“fealdad del pecado” y la “excelencia de la castidad”, y éstos ocupan un tercio del libro. En total

700 versos en 200 poemas que aderezan la prosa y priorizan la teología a la poesía. En los 28

capítulos va desgranando la esencia y los orígenes del amor y las primeras señales a través de la

mirada, cuando señala: “Mis ojos no se paran sino donde tú estás, debes tener las propiedades

que dice del imán. Los llevo adonde tú vas y conforme te mueves, como en gramática el atributo

precede al nombre”. O las señales de las lágrimas: “Las nubes han tomado lecciones de mis ojos

y todo lo anegan en lluvia pertinaz, que esta noche, por tu culpa, llora conmigo y viene a

distraerme en mi insomnio”.

Además, plantea las cualidades del amor, sobre quien se enamora en sueños o al serle descrito, o

con una sola mirada, o con el largo trato. Sobre las señales con los ojos, sobre las cartas de amor

y sobre el mensajero, el espía, el secreto, el sometimiento, la desavenencia, el censor, el amigo

dispuesto a ayudar, el calumniador. Sobre la unión amorosa: “Desearía rajar mi corazón con un

cuchillo, meterte dentro de él y luego volver a cerrar mi pecho, para que estuvieras en él, y no

habitaras en otro, hasta el día de la resurrección y del juicio final; para que moraras en él durante

mi vida y, a mi muerte, ocuparas las entretelas de mi corazón en la tibieza del sepulcro”.

Sobre el retraimiento, sobre la fidelidad, sobre la separación, el contentarse, la consunción, el

consuelo del olvido, y sobre la muerte: “Las gentes saben que soy un mancebo enamorado; que

estoy triste y afligido: pero ¿por quién? Cuando ven cómo me hallo, se cercioran; pero si indagan

se pierden en conjeturas. Mi amor es como un escrito cuyo trazo es firme, pero que se resiste a la

interpretación: o como la voz de la paloma en el boscaje, que repite su canción de rama en rama y

cuyo murmullo deleita nuestros oídos, pero cuyo sentido es enigmático y oscuro”.

El collar de la paloma influyó en los trovadores occitanos y su concepto del “Amor cortés”, en la

gaya ciencia (el arte poético) de Guillermo IX de Aquitania (1071-1126), así como en el Arcipreste

de Hita y su “Libro del buen amor” año 1330. El historiador al-Marrakusi, en su “Historia de los

almohades”, siglo XIII, denomina a Ibn Hazm como “el más célebre de todos los sabios de al-

Andalus”. De hecho, su influencia fue profunda tanto en el mundo musulmán como en el cristiano:

“Vete en mal hora, joya de la China. Me basta con mi rubí de Al-Andalus”.

Al-Mutamid, Muhammad ibn ‘Abbad al-Mu‘tamid (Beja, Portugal, 1040 - Agmat, Marruecos,

1095). Rey taifa de Sevilla (1069-1090). Segundo hijo de al-Mutadid (1042-1069), se convirtió en

heredero cuando su hermano mayor fue mandado ejecutar por su padre por supuesta traición. A

los doce años, su padre lo envió como gobernador a Silves, en el Algarve, para ser educado por el

poeta Abu Bakr Ibn Ammar de Silves (1031-1086), el Abenámar de los cristianos, el cual se

convertiría en amigo y favorito. En el segundo año de su reino, al-Mutamid anexionó la taifa de

Córdoba. Esto supuso una amenaza para la taifa de Toledo, cuyo rey, Al-Mamun en 1075 se

apoderó de esta ciudad. Al-Mutamid reconquistó Córdoba en 1078, al tiempo que todas las

posesiones del reino de Toledo, situadas entre el Guadalquivir y el Guadiana, pasaron a formar

parte del reino de Sevilla. Sintiéndose amenazado por Alfonso VI de León, que había conquistado

Toledo en 1085, decidió pedir auxilio a los almorávides africanos, a los que ayudó a derrotar a los

cristianos en Zalaca (1086). Al-Mutamid se dirigió de nuevo a Marrakech para pedir ayuda. Los

almorávides volvieron a la península en 1088, pero esta vez fueron conquistando uno a uno todos

los reinos de taifas. Al-Mutamid fue depuesto en 1090 y desterrado y encarcelado en Agmat,

Poeta. Al-Mu‘tamid fue un notable poeta desde su juventud hasta su exilio y por ser rey nunca

necesitó mecenas. Durante su reinado la cultura floreció en Sevilla. En su corte gozaron de favor

los poetas y literatos, como Ibn Zaydún (1003-1071), el siciliano Ibn Hamdis (1056-1133), Ibn al-

Labbana de Denia (+1113). También la visitaron intelectuales como Ibn Hazm (994-1063), una de

las figuras centrales de la cultura andalusí, el geógrafo Al-Bakrí (1040-1094) y al astrónomo

Azarquiel de Toledo (1029-1087). Paseando un día a orillas del Guadalquivir con su amigo Ibn

Ammar, jugaban a improvisar poemas.

Al levantarse una ligera brisa sobre el río, dijo al-Mutamid: "El viento tejiendo lorigas en las

aguas”. Ibn Ammar no tuvo tiempo de responder, puesto que ambos oyeron una voz femenina que

completaba la rima: "¡Qué coraza si se helaran!". Era una joven bellísima llamada Rumaikiyya,

esclava de un arriero. Al-Mutamid quedó inmediatamente enamorado, la llevó a su palacio y la

hizo su esposa principal tomando el nombre de Itimad, y ella le acompañó toda su vida.

Eduardo Paniagua

Ibn Hazm

Abu Muḥammad ʿAli ibn Aḥmad ibn Saʿīd ibn Ḥazm, known among Christians as Abén Házam

(Córdoba 994 - Montíjar, Huelva 1064), was an Andalusi philosopher, theologian, historian,

storyteller and poet, considered the ‘Father of Comparative Religion’. His ancestors were Muladís,

Hispanic Christians converted to Islam. He was born towards the end of the 10th century before

the crisis of the Caliphate of Cordoba. His grandfather moved to the capital of the Caliphate and

his father, Ahmad, was Almanzor's vizier. Ali received his education at the Cordovan court of the

al-Zahira palace. As a member of the aristocracy, he was on the side of the Umayyads in the

Cordovan civil war waged against the new Amiri lineage of Almanzor. His father, Ahmad, died in

1012 and Ali was exiled to Almeria at the age of 18, from where he supported a new Umayyad

pretender to the Caliphate and was taken prisoner in the Zirid kingdom of Granada. From there he

withdrew to Játiva, where in 1022 at just 28 years of age and at the behest of his friend

Muhammad Ibn Ishaq, he wrote the book that is now a thousand years old, The Dove’s Necklace.

In 1023, Cordoba elected Abderraman V as the new Caliph, who appointed Ibn Hazm to be his

vizier. However, the Caliph’s rule lasted only one month and after the ruler was executed, Ibn

Hazm was again imprisoned. Ali gave up politics to devote himself to the legal and theological

studies of the Zahirid school, giving lessons together with his teacher Abū-l-Jiyār of Santarén in the

Mosque of Córdoba, until in 1027 he was reported for contravening the official Maliki school.

Disenchanted with politics and teaching, he abandoned public life and devoted his time to visiting

the various taifa kingdoms as an activist and scholar. In 1039, after taking refuge in Mallorca, he

fell out with scholars and kings such as Al Mutadid of Seville, father of Al Mutamid. So much

controversy led to the drastic burning of his books. This inspired Ibn Hazm's famous lines: ‘Stop

setting fire to scrolls and papers and show your science so that the one who knows may be seen.

Even if you burn the paper, you will never burn what it contains, since I carry it within me, it always

travels with me when I ride, it sleeps with me when I rest, and in my tomb it will be buried’.

(Translation into Spanish by José Miguel Puerta Vílchez). He continued the life of a wandering

sage until the end of his days when, exiled by Al-Mutadid, he retired with his children to the family

country house in Montíjar.

Work: He produced a huge number of works of thousands of pages. He wrote historical works,

such as Epistle in praise of al-Andalus, The Bride’s Embroidery, Arab lineages and his most

important work, Critical history of religions, sects and schools, in which he outlined the features of

anti-religious, including anti-Islamic, philosophical systems. This work was the first treatise on the

comparative history of religions to be written in any language. Characters and Conduct is a didactic

work, as is A Theological Polemic with Ibn Nagrella, a Jewish poet, chief of the army and vizier of

the kingdom of Granada (1035-1066). He also wrote numerous philosophical works, basing his

thought on Aristotle. Relating truths to theology, he approached and preceded the postulates of St.

Thomas. His Epistle on the lawfulness or unlawfulness of singing and instrumental music, is also

worth mentioning. In this work, he compares the positions of the schools of Islamic jurisprudence

and the positions of the Eastern and Andalusian faquis on the acceptance or rejection of music and

the sale and purchase of highly qualified singing slaves (al-qiyan), women who were renowned for

their refined education. These arguments led him to position himself in favour of music as a

discipline, including music among the sciences of the Pythagorean quadrivium, together with

Arithmetic, Geometry and Astronomy.

His most famous work is Ṭawq al-ḥamāma or The Dove’s Necklace, a literary gem in prose and the

first known treatise on love and lovers. The book is actually entitled The turtledove's necklace and

the shadow of the cloud. This long title in the Semitic language is very suggestive, since it

combines opposing symbols of the ephemeral and passing with the profound and spiritual. The

ring of coloured feathers around the turtledove’s neck as a divine decoration of fleeting carnal love,

the prestige the dove won for its services to Noah as messenger in his Ark in the flood, and the

dove as the Holy Spirit in the baptism of Jesus Christ in the Jordan. The ephemeral shadow of the

cloud that passes quickly by, like life or some kind of love, or like the divine shadow of the cloud

that accompanied the chosen people in the desert. The title in Andalusi is even more suggestive,

being a subtle couplet ‘Tawq al-hamáma wa-zill al-gamáma’, which literally means: I carry your

intimate friendship with the same honour with which the turtledove wears its ring of feathers.

The book reflects on the true essence of love, seeking to discover what is common and

unchanging through the centuries and civilizations. Ibn Ḥazm includes ‘udrí love’, which is of

Neoplatonic influence, thus adhering to the literary and aesthetic trend of the Banū 'Uḏra or ‘Sons

of Purity’ of Baghdad, brought to the peninsula by the astronomer Maslama al Mayriti (Madrid c.

950- Córdoba c. 1007) and quoted in ‘the necklace’. The book can also be considered a diwan, or

poetic anthology on the theme of love, as it contains his elegant and refined poems with

autobiographical details. Ibn Hazm was a man of deep religious convictions and largely criticised

the relaxation of customs in Al-Andalus. The book develops an exquisite way of conceiving beauty,

love and literature, mixing Neoplatonism with stoicism. Love arises because the soul is beautiful

and seeks beauty, and if it is true love, it is eternal. Love that stops at physical beauty is carnal

love, which has little value for him: ‘I love you with an unchanging love, while so many human loves

are nothing but mirages. I consecrate to you a pure and undefiled love: your affection is visibly

engraved and written in my entrails.’

The book finishes after 28 chapters, the days of the month, the letters of the Arabic alphabet, but

has two more chapters that make up a third of the book and provide many facts, dates and

theological content on the ‘ugliness of sin’ and the ‘excellence of chastity’. In total, 700 verses in

200 poems, poems that embellish prose and prioritise theology over poetry. In the 28 chapters he

unravels the essence and origins of love and the first signs through a glance, when he says: ‘My

eyes rest only where you are, you must have the properties said to be of the magnet. I take them

wherever you go and as you move, as in grammar the attribute precedes the noun’. Or signs of

tears: ‘The clouds have taken lessons from my eyes and flood everything with stubborn rain, which

tonight, because of you, cries with me and comes to distract me in my insomnia’.

He also discusses the qualities of love, considering the one who falls in love in dreams or on

hearing a description, or with a single glance, or through a long relationship. On signs made with

the eyes, on love letters and on messengers, spies, secrets, subjection, disagreement, censors,

friends ready to help, slanderers. On loving union: ‘I would like to slit my heart with a knife, put you

inside it and then close my chest again, so that you would be in it, and not dwell in another, until

the day of resurrection and final judgement; so that you would dwell in it during my life and, at my

death, occupy the lining of my heart in the warmth of the tomb’.

On withdrawal, on fidelity, on separation, contentment, consumption, the consolation of oblivion,

and on death: ‘People know that I am a young man in love; that I am sad and afflicted: but for

whom? When they see how I am, they are certain; but if they inquire, they are lost in conjecture.

My love is like writing whose script is firm, but which resists interpretation: or like the voice of the

dove in the forest, which repeats its song from branch to branch and whose murmur delights our

ears, but whose meaning is enigmatic and obscure’.

The dove’s necklace influenced the Occitan troubadours and their concept of ‘courtly love’, the

gaya ciencia (the poetic art) of William IX of Aquitaine (1071-1126), as well as the Archpriest of

Hita and his Book of Good Love (1330). The historian al-Marrakusi, in his 13th century History of

the Almohads, calls Ibn Hazm ‘the most famous of all the wise men of Al-Andalus’. In fact, his

influence was profound in both the Muslim and Christian worlds: ‘Go in evil hour, jewel of China.

My ruby of Al-Andalus is enough for me’.

Al-Mutamid, Muhammad ibn 'Abbad al-Mu'tamid (Beja, Portugal, 1040 - Aghmat, Morocco, 1095).

Ruler of the taifa of Seville (1069-1090). He was the second son of al-Mutadid (1042-1069), and

became heir when his father ordered the execution of his older brother for alleged treason. At the

age of twelve, his father sent him to be the governor of Silves, in the Algarve, to be educated by

the poet Abu Bakr Ibn Ammar of Silves (1031-1086), known by the Christians as Abenámar, who

was to become a friend and favourite. In the second year of his reign, al-Mutamid annexed the

Taifa of Cordoba, which posed a threat to the Taifa of Toledo, whose king, Al-Mamun seized the

city of Cordoba in 1075. Al-Mutamid reconquered Cordoba in 1078, while all the possessions of the

kingdom of Toledo located between the Guadalquivir and the Guadiana became part of the

kingdom of Seville. Feeling threatened by Alfonso VI of León, who had conquered Toledo in 1085,

Al-Mutamid decided to ask the African Almoravids for help, since he had helped them to defeat the

Christians at Sagrajas (1086). Al-Mutamid went back to Marrakech and it was his turn to ask for

help. The Almoravids returned to the peninsula in 1088, but this time they conquered all the taifa

kingdoms one by one. Al-Mutamid was deposed in 1090 and banished and imprisoned in Aghmat.

Poet. Al-Mu'tamid was a remarkable poet from his youth until his exile, and because he was a king

he never needed patrons. During his reign, culture flourished in Seville. Poets and literati such as

Ibn Zaydún (1003-1071), the Sicilian Ibn Hamdis (1056-1133), Ibn al-Labbana of Denia (d.1113)

enjoyed favour at his court, which was also visited by intellectuals such as Ibn Hazm (994-1063),

one of the central figures of Andalusi culture, the geographer Al-Bakri (1040-1094) and the

astronomer Azarquiel of Toledo (1029-1087). Strolling one day on the banks of the Guadalquivir

with his friend Ibn Ammar, the two played at improvising poems.

As a light breeze rose on the river, al-Mutamid said: "The wind weaving loricas in the waters". Ibn

Ammar had no time to reply, for they both heard a female voice completing the rhyme: "What a

breastplate if they were to freeze!". The voice came from a beautiful young woman named

Rumaykiyya, a slave of a muleteer. Al-Mutamid was immediately smitten, took her to his palace

and made her his chief wife with the name of Itimad, and she accompanied him all his life.

Eduardo Paniagua

Compartir

-

Envío gratis en pedidos mayores a 50 €.

Entrega en 5-7 días laborables para pedidos en España, en el caso de envíos fuera de España el tiempo de envío podría ser algo mayor.

-

Todo el trabajo de Pneuma Music se ha realizado en España.

Música medieval española inédita hasta el momento. Sus discos, con formato Digipack de cubierta de cartón y libreto interior (bilingüe + idioma original), quieren acercarse a una obra de arte total.