pneumamusic

PN 1410 SERRANILLAS DEL MARQUES DE SANTILLANA (1388 -1458)

PN 1410 SERRANILLAS DEL MARQUES DE SANTILLANA (1388 -1458)

No se pudo cargar la disponibilidad de retiro

Índice

Índice

SERRANILLAS DEL MARQUES DE SANTILLANA (1388 -1458)

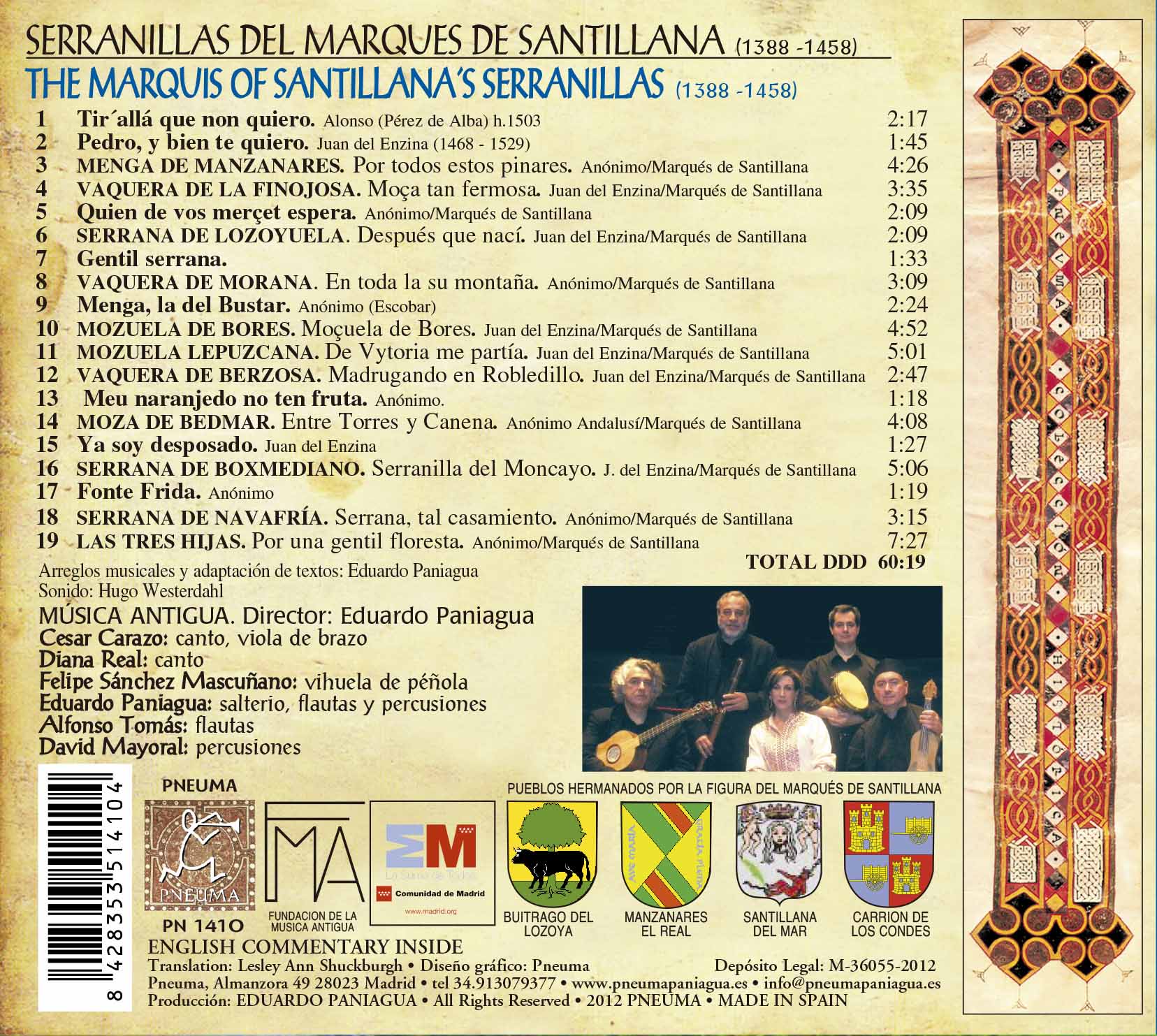

MÚSICA ANTIGUA. Director: Eduardo Paniagua

Cesar Carazo: canto, viola de brazo

Diana Real: canto

Felipe Sánchez Mascuñano: vihuela de péñola

Eduardo Paniagua: salterio, flautas y percusiones

Alfonso Tomás: flautas

David Mayoral: percusiones

1 Tir´allá que non quiero. Alonso (Pérez de Alba) h.1503 2:17

2 Pedro, y bien te quiero. Juan del Enzina (1468 - 1529) 1:45

3 MENGA DE MANZANARES. Por todos estos pinares. Anónimo/Marqués de Santillana 4:26

4 VAQUERA DE LA FINOJOSA. Moça tan fermosa. Juan del Enzina/Marqués de Santillana 3:35

5 Quien de vos merçet espera. Anónimo/Marqués de Santillana 2:09

6 SERRANA DE LOZOYUELA. Después que nací. Juan del Enzina/Marqués de Santillana 2:09

7 Gentil serrana. 1:33

8 VAQUERA DE MORANA. En toda la su montaña. Anónimo/Marqués de Santillana 3:09

9 Menga, la del Bustar. Anónimo (Escobar) 2:24

10 MOZUELA DE BORES. Moçuela de Bores. Juan del Enzina/Marqués de Santillana 4:52

11 MOZUELA LEPUZCANA. De Vytoria me partía. Juan del Enzina/Marqués de Santillana 5:01

12 VAQUERA DE BERZOSA. Madrugando en Robledillo. Juan del Enzina/ Marqués de Santillana 2:47

13 Meu naranjedo no ten fruta. Anónimo. 1:18

14 MOZA DE BEDMAR. Entre Torres y Canena. Anónimo Andalusí/Marqués de Santillana 4:08

15 Ya soy desposado. Juan del Enzina 1:27

16 SERRANA DE BOXMEDIANO. Serranilla del Moncayo. J. del Enzina/Marqués de Santillana 5:06

17 Fonte Frida. Anónimo 1:19

18 SERRANA DE NAVAFRÍA. Serrana, tal casamiento. Anónimo/Marqués de Santillana 3:15

19 LAS TRES HIJAS. Por una gentil floresta. Anónimo/Marqués de Santillana 7:27

TOTAL 60:19

Arreglos musicales y adaptación de textos: Eduardo Paniagua

Sonido: Hugo Westerdahl

Producción: EDUARDO PANIAGUA • 2012

Las fuentes textuales de los poemas son fundamentalmente dos cancioneros, el ms. 2655 de la Biblioteca Universitaria de Salamanca (Sd) y el ms. 3677 de la Biblioteca Nacional de Madrid (Ma). La fuente musical es el Cancionero Musical de Palacio, CMP (Madrid, Real Biblioteca, MS II – 1335), los arreglos y adaptaciones son de Eduardo Paniagua.

Eduardo Paniagua, Premio mejor Intérprete de Música Clásica 2009 de la Academia de la Música de España. Nominado premios UFI 2010, 2011y 2012 música clásica (Unión Fonográfica Independiente). Nacido en Madrid en 1952, es arquitecto y especialista de la música de la España medieval. En 1968 graba cuatro discos con ATRIUM MUSICAE. Miembro fundador de CÁLAMUS y HOQUETUS, se especializa en música arábigo-andaluza. En 1994 crea los grupos MÚSICA ANTIGUA e IBN BÁYA, para interpretar las Cantigas de Alfonso X y la Música Andalusí y funda el sello discográfico PNEUMA. En 2011 crea la FUNDACIÓN DE LA MÚSICA ANTIGUA. Por su trabajo y por la difusión de estas músicas inéditas está recibiendo excelentes críticas y premios internacionales.

Descripción

Descripción

EL MARQUÉS DE SANTILLANA (1388-1458)

Don Íñigo López de Mendoza, Marqués de Santillana, nació en Carrión de los Condes, Palencia, en 1388. Fue hijo de don Diego Hurtado de Mendoza y de doña Leonor de la Vega, dama inteligente y rica. Al morir su padre, el pequeño Iñigo quedó al cuidado exclusivo de su madre y de su abuela. Joven todavía, se casó con doña Catalina de Figueroa. Como los caballeros de su tiempo tomó parte en la política, unas veces al lado del rey Juan II de Castilla y otras contra él. Participó en varias batallas y por su esfuerzo en la contienda de Olmedo, el rey le concedió los títulos de Marqués de Santillana y Conde de Manzanares. Más tarde se retiró a su palacio en Guadalajara, en donde falleció en 1458.

El Marqués de Santillana, además de buen político y guerrero, fue un hombre muy culto. Poseía una de las mejores bibliotecas de su tiempo y se le considera el primer poeta del siglo XV. Sus principales obras son: La Comedieta de Ponza, Bías contra Fortuna, Proverbios y sus numerosos Sonetos al estilo italiano. Aunque es muy conocido por sus poesía consideradas de arte menor; Serranillas, Dezires y Canciones. Es en ellas donde mejor se puede observar la inspiración poética, la sencillez y el encanto inimitables de este poeta castellano renacentista.

SERRANILLAS

Las serranillas son breves cantares líricos que describen el encuentro entre un caminante y una moza agreste que le ayuda a encontrar el puerto en una sierra. Influidas por la pastorela francesa, el caminante se convierte en un caballero que trata de enamorar a la moza, siendo rechazado o aceptado.

Íñigo López escribe sus serranillas como divertimiento aristocrático palaciego en el género poético cortesano de las canciones de aventuras al regreso de un viaje. Ello otorga un carácter lúdico y picante a los relatos del encuentro con una pastora o serrana. Sus serranillas constituyen un ciclo poético y guardan relación con sus andanzas viajeras o militares por las sierras del Moncayo en su campaña en Agreda como frontero en 1429; los viajes a Buitrago a principios de 1430; la comarca de Liébana en 1430; sus estancias en el Real de Manzanares entre 1430 y 1438; las tierras de Jaén que recorrió en 1438 durante su campaña de Huelma y Bexis; la provincia de Córdoba, donde se ambienta La vaquera de la Fino josa en 1431; las tierras de Álava en 1440, cuando viaja a la frontera de Navarra; y con ocasión de las justas celebradas en Madrid en 1433 y en Valladolid en 1434.

En las serranillas del Marqués confluyen las dos formas del género en la tradición medieval. Por un lado el modelo idealizador francés e italiano de la pastorela, con el ofrecimiento del caballero a hacerse pastor, para mejor servirla como amante por su belleza, haciendo símil entre una dama y una pastora. Por otro, el modelo realista peninsular de la figura de la serrana salteadora y agreste (Morana, Boxmediano, Manzanares), ya explorado anteriormente por el Arcipreste de Hita.

Por ello este ciclo de serranillas ofrece una gran variedad en la combinación de motivos y elementos poéticos. Sabe variar los escenarios geográficos y las situaciones de la personalidad de la serrana con la estrategia amorosa del caballero. Los diálogos y el desenlace son de gran atractivo. Estos poemas consiguen fundir y sublimar sus distintas emociones poéticas cuando son adaptados a los cantos polifónicos del momento. El amor y el deseo, templado por la melancolía e impulsado por los estribillos populares, elevan el sentir espontáneo del Marqués de Santillana al plano de arte sutil y reflexivo.

INTERPRETACIÓN DE LAS SERRANILLAS

Compone el programa de esta grabación las 10 serranillas del Marqués de Santillana, una de sus numerosas canciones y un villancico-serranilla dedicado a sus hijas. Completa el repertorio obras instrumentales de carácter popular o campesino recogidas de los Cancioneros del siglo XV.

Las Serranillas, Dezires y Canciones del Marqués de Santillana se conservan publicadas sin música. La rica producción poético musical de los reinos españoles de finales del siglo XIV y primera mitad del XV se ha perdido en incendios y batallas. Los textos de cientos de poemas y canciones de esta época se recogen en el Cancioneros de Baena 1426-1445 (576 composiciones) y en el Cancionero de Stúñiga 1460. Para cantar estas obras practicamos la técnica llamada contrafacta, es decir la de tomar prestada la música preexistentes o de la época, recogidas en los cancioneros musicales del siglo XV. Ello requiere la adaptación del texto y el arreglo musical con la sustitución del texto original por la serranilla. Para conservar el carácter de estos poemas, se han elegido obras musicales de aire popular y campesino, y sobre todo adaptables al metro poético, ritmo, rima y acento musical del poema. Obras sencillas a 3 y 4 voces, poco conocidas pero muy hermosas, anónimas en su mayoría, y también canciones de juventud de Juan del Enzina, seleccionadas por su riqueza de formas. En ellas se destaca la melodía principal con el canto masculino como voz del poeta-caballero, que viaja por sierras y campos en su encuentro con las mozas serranas. El canto femenino tiene un carácter popular encarnando las respuestas de la serranilla a los requerimientos del caballero.

En esta grabación se ha dado protagonismo a la utilización de la vihuela de péñola del siglo XV interpretada con la púa o péñola. La técnica de la púa de la vihuela limita la polifonía que normalmente se produce al tañer el instrumento con los dedos, manera propia de tocar la vihuela de mano en el siglo XVI. La púa permite a su vez explorar los acordes y rasgueados verticales en técnica híbrida entre el laúd árabe y la cítola, guitarra o bandurria medieval del siglo XIV. Este instrumento interpreta los bajos y la línea armónica de las canciones cuando esto es posible.

El salterio, modelo del siglo XIV también tocado con púas, es entregado a las primeras voces doblando al canto con pequeños apoyos de la armonía. Las flautas dulces se usan como respuesta al canto, o en la segunda o tercera voz de la polifonía tratada instrumentalmente. La percusión dinamiza el discurso sobre la base del gran tambor de dos parches, el tambor cáliz de un parche, el pandero y las panderetas hispanas.

Eduardo Paniagua

LA VIHUELA DE PÉÑOLA

Para el público aficionado, para una gran mayoría de músicos, para muchos especialistas en música antigua… incluso para muchos musicólogos, el concepto de vihuela es rotundo e indiscutible. Como es normal, todos sus cerebros vuelan al instrumento del siglo XVI, a Luys Milan, Narvaez, Valderrábano… etc. Es natural porque tenemos una gran información (si de “gran información” se puede hablar en estos asuntos) que ocupa unos 30 o 35 años del siglo XVI, si contamos los propios libros de los vihuelistas más el libro de Bermudo. En el mejor de los casos, contando con otros textos colaterales y algunos dudosos, podríamos llegar a hablar de 100 años de información sobre la vihuela (de mano) que más o menos todo el interesado tiene en la cabeza.

¿Qué pasa con la vihuela de péñola? Siempre arrinconada, si no olvidada, en las clasificaciones organológicas. Que sepamos, las vihuelas pulsadas durante los siglos XIII, XIV y XV fueron siempre vihuelas de péñola, es decir, de plectro o de púa. Péñola es voz antigua de pluma, del latín penna, haciendo referencia al cañón de las plumas de diferentes aves con el que los músicos fabricaban su plectro para tañer.

La primera obra escrita que nos ha llegado para plectro es una intabulación (la primera tablatura de la historia que conocemos) de finales del XIV, en la que un laudista anónimo escribe a dos voces una interesante glosa de una famosísima canción de Francesco Landini “Questa Fanciulla”. Esto refrenda que con un instrumento de plectro se puede hacer y se hacía polifonía, aunque fuera la más básica a dos voces.

El uso y la técnica de la péñola debieron, por lógica, ir cambiando según la textura de la música. Además, en España, tocaban con péñola y con gran virtuosismo los maestros de laúd árabe y mudéjar. Muchos efectos y mecánicas de esos músicos debieron pasar a formar parte de los recursos plectrísticos de los tañedores cristianos de vihuela y otros instrumentos similares.

Conocer qué pudo ocurrir ocurre con la vihuela de péñola en la España del XV es cuestión de ponerse a experimentar, leer música y más música con el instrumento y el plectro en las manos y ver qué sucede… y sucede que para cada uno de los distintos estilos del XV encontramos una manera diferente de actuar con la péñola. Y sólo se descubre al hacerlo.

Bermudo, a mediados del XVI, habla de polifonías cantadas “por hombres y mujeres que no saben de música”. Suelen ser canciones a tres voces con unas características que aquel que estudie los cancioneros puede reconocer a primera vista. Estas obras curiosamente, son las más antiguas en los cancioneros de Palacio y de la Colombina. Son la “música golpeada” de la época, es decir, una polifonía muy vertical en la que la vihuela de péñola a veces se puede permitir el lujo de tocar a tres voces y, en algún caso, ¡hasta a cuatro! Curioso y extraño en un instrumento de plectro y en una época en la que ni siquiera existía el concepto de acorde.

Cuando Eduardo Paniagua me invitó a esta grabación de las Serranillas de Santillana, nos pareció un reto y la perfecta ocasión para demostrar o más bien mostrar todas las particularidades de la VIHUELA DE PÉÑOLA.

¿Es la vihuela de péñola, en un repertorio como éste, el origen remoto de la guitarra rasgueada con acordes tan propias de finales del XVI y, sobre todo, del barroco? Es posible. Pero lo que más nos ha importado es mostrar en primicia artística cómo podían sonar las Serranillas de principios del siglo XV con la técnica instrumental polifónica basada en el uso de la púa del siglo XV.

Felipe Sánchez Mascuñano

THE MARQUIS OF SANTILLANA´S SERRANILLAS (1388 -1458)

THE MARQUIS OF SANTILLANA (1388-1458)

Íñigo López de Mendoza, Marquis of Santillana, was born in Carrión de los Condes, Palencia, in 1388. He was the son of Diego Hurtado de Mendoza and the rich and intelligent Leonor de la Vega. When his father died, young Iñigo was left in the care of his mother and his grandmother and married Catalina de Figueroa when still at a young age.

Just like all the knights of his time, he took part in politics, sometimes on the side of the king John II of Castile and others against him. He fought in several battles and the king awarded him the titles of Marquis of Santillana and Count of Manzanares for his efforts in the battle at Olmedo. Later he retired to his palace in Guadalajara, where he died in 1458.

As well as a good politician and warrior, the Marquis of Santillana was a very cultured man. His libraries were the best at the time and he was considered to be the first poet of the 15th century. His main works were: the Comedieta de Ponza, Bías contra Fortuna, Proverbios plus his numerous Sonnets in Italian style. He is also very well known for the poetry he wrote that is considered to be a minor art; Serranillas, Dezires and Canciones. It is in these works that the poetic inspiration, simplicity and inimitable charm of this Castilian renaissance poet can best be appreciated.

Eduardo Paniagua, born in Madrid in 1952, is an architect as well as a specialist in the music of Medieval Spain. From1968 to 1983 made twenty recordings with Atrium Musicae. As a founder member of the groups Calamus and Hoquetus. In 1994 he created the groups MUSICA ANTIGUA and IBN BAYA to work on the Cantigas of Alfonso X and music from Moorish Spain. Founded and directed the record label PNEUMA. As well as international awards Eduardo has received excellent reviews from the critics for his work and publication of this previously un-released music. He is considered a “cultural ambassador” by his country for his contribution to the dialogue between Mediterranean cultures, and was nominated Best Classical Musical Artist by the Spanish Academy of Music in 1997, 2000 and 2004. In 2009 he won this prize.

SERRANILLAS

The serranillas are short lyrical songs (literally little mountain songs in Spanish) that describe a meeting between a traveller and a country girl who helps him to find a mountain pass. In the serranillas the wayfarer becomes a knight who attempts to woo a girl who either warms to his advances or not, after the manner of the French pastoral.

Íñigo López wrote his serranillas as an aristocratic palace entertainment in the courtly poetic genre of songs that the traveller sang on his return from a journey, to recount the adventures he had had on the way. The stories about the encounter with a shepherdess or mountain girl are therefore light-hearted and rather risqué. His serranillas make up a poetic cycle and relate his own travelling or military adventures including his exploits in the Moncayo mountains in the Agreda campaign as border general in 1429; his journeys to Buitrago at the beginning of 1430; his exploits near Liébana in 1430; his stays at Real de Manzanares between 1430 and 1438; his travels through Jaén in 1438 during his Huelma and Bexis campaigns; his time in the province of Córdoba, which is the setting of “La Vaquera de la Finojosa” (The Fine Cowgirl) in 1431 and his travels through Álava in 1440 to the border with Navarre. They also celebrate the occasion of the jousting tournaments held in Madrid in 1433 and in Valladolid in 1434.

The two forms of the genre in the medieval tradition converge in the Marquis’ serranillas. On the one hand is the French and Italian idealizing model of the pastourelle, in which the knight offers to become a shepherd, in order to serve the shepherdess better as a lover, thinking purely of her beauty and thus drawing a comparison between a lady and a shepherdess. On the other hand, the peninsular realist model of a wild, highwaywoman (Morana, Boxmediano, Manzanares) which the Archpriest of Hita had already explored.

For this reason, this cycle of serranillas displays great variety in the combination of motifs and poetic elements. Geographic settings and the situations created by the mountain girl’s personality are woven with the knight’s strategy for love, and the dialogues and the dénouement are very attractive. These poems successfully blend and sublimate different poetic emotions when they are adapted to the polyphonic songs of the time. Love and desire, tempered by melancholy and driven by popular refrains, raise the spontaneous feelings of the Marquis of Santillana to the plane of subtle and thoughtful art.

The texts of the poems are basically found in two songbooks, manuscript 2655 in the Salamanca University Library (Sd) and manuscript 3677 in the National Library in Madrid (Ma). The music comes from the Cancionero Musical de Palacio (Palace Musical Songbook), CMP (Madrid Royal Library, MS II – 1335) the arrangements and adaptations are by Eduardo Paniagua.

PERFORMING THE SERRANILLAS

This recording includes the Marquis of Santillana’s 10 serranillas, one of his numerous songs and a villancico-serranilla song dedicated to his daughters. The repertoire is completed by popular or country instrumental works found in the 15th century songbooks.

The Serranillas, Dezires (Sayings) and Canciones (Songs) by the Marquis of Santillana are published without music and have been preserved that way. The rich poetic and musical production of the Spanish kingdoms at the end of the 14th century and first half of the 15th century has been lost in fires and battles. The texts of hundreds of poems and songs from this time are gathered in the Baena Songbooks 1426-1445 (576 compositions) and in the Stúñiga Songbook 1460. The technique known as contrafactum is therefore used to sing these works. Pre-existing music or music from the time, found in 15th century musical songbooks, is borrowed, the text is then adapted to fit it, and the music arranged. The original text is thereby replaced by the serranilla. Musical works with a popular or country tone have been chosen to retain the character of the poems. Above all, tunes are used that can be adapted to the poetic metre, rhythm and musical accent of the poem. They are simple works in 3 and 4 parts that are not well known but very beautiful and mostly anonymous. Some songs from Juan del Enzina’s young days have also been chosen for their richness of form. In all the songs the male voice playing the part of the poet-knight dominates as the main melody, as he travels through the mountains and countryside hoping to encounter mountain maids. The female voice singing the mountain girl’s responses to the knight’s entreaties are given a popular tone.

On this recording prominence has been given to the 15th century vihuela de péñola played with a plectrum or quill. The plectrum technique limits the polyphony that is usually produced when strumming the vihuela with the fingers, which is the proper way to play the 16th century hand-held vihuela. On the other hand, the plectrum enables the musician to explore chords and strum vertically in a hybrid technique between the Arab lute and the citole, a 14th century medieval guitar or mandolin. The latter plays the bass and the harmonic line of the songs whenever possible.

The 14th century psaltery, also played with plectrums, concentrates on the first voices backing up the singing with harmony. The recorders are used in response to the voice, or to play the second or third parts of the polyphony when instrumental. The percussion, which includes a large double-headed drum, the single-headed goblet drum, the tambourine and the Spanish tambourines, gives life to the discourse.

Eduardo Paniagua

THE VIHUELA DE PÉÑOLA

For the amateur audience, a great majority of musicians, many specialists in ancient music…and even for many musicologists, the concept of vihuela is categorical and indisputable. As is to be expected, all minds turn to the 16th century instrument, to Luys Milan, Narvaez, Valderrábano…etc. This is natural because we have extensive information (if “extensive information” is the correct expression in these matters) covering some 30 or 35 years of the 16th century, if we count the books by the vihuela players plus Bermudo’s book. At best, if we include other secondary texts and some dubious ones, we could be talking about 100 years of information on the vihuela (hand held) of which more or less all interested parties are aware.

What about the vihuela de péñola, or plucked vihuela? Always left aside, if not forgotten, in organological classifications. As far as we know, plucked vihuelas during the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries were always vihuelas de péñola, that is to say, played with a plectrum or quill. Péñola is the old word for quill, from the Latin penna, referring to the quills from the feathers of the birds that musicians used to make a plectrum to strum with.

The first written work for plectrum that has reached us today is a tablature (the first known written tablature in history) from the end of the 14th century, in which an anonymous lutenist writes an interesting gloss on a very famous song by Francesco Landini ""Questa Fanciulla"" for two voices. This endorses the view that polyphony can be, and was, played on plectrum instruments, even if it was the most basic in two parts.

The use of the quill and its technique had to, logically, change according to the texture of the music. Moreover, in Spain, Arab and Mudejar lute masters played with a quill with great virtuosity. Many of these musicians’ effects and mechanics must have become part of the plectrum resources of the Christian vihuela players and performers playing other similar instruments.

Knowing what could have happened with the vihuela de peñola in 15th century Spain is a matter of experimenting, reading music and more music with the instrument and the plectrum in hand to see what happens ... and what happens is that for each of the different 15th century styles we find a different way of using the quill. And this is only discovered by playing the instrument.

In the mid-16th century, Bermudo speaks of polyphony sung ""by men and women who did not know music"", usually songs in three parts with characteristics that anyone who studies the songbooks can recognize at first glance. Curiously, these works are the oldest in the Palace and the Colombina songbooks. They are the ""struck music"" of the time, that is, a very vertical polyphony in which the vihuela de peñola can sometimes be played in three parts and, in some cases, up to four! Curious and strange for a plectrum instrument and at a time when the concept of a chord did not even exist.

When Eduardo Paniagua invited me to this recording of Santillana’s Serranillas it struck me as a challenge and the perfect opportunity to demonstrate, or rather show, all the peculiarities of the VIHUELA DE PÉÑOLA.

Is the vihuela de péñola, in a repertoire like this, the remote predecessor of the strummed guitar whose chords were so typical in the late sixteenth century and especially Baroque period? Possibly. But what was most important for us was to show for the first time what the early fifteenth century Serranillas might sound like, as a sort of artistic novelty, with the polyphonic instrumental technique based on the fifteenth century plectrum.

Felipe Sánchez Mascuñano

Compartir

-

Envío gratis en pedidos mayores a 50 €.

Entrega en 5-7 días laborables para pedidos en España, en el caso de envíos fuera de España el tiempo de envío podría ser algo mayor.

-

Todo el trabajo de Pneuma Music se ha realizado en España.

Música medieval española inédita hasta el momento. Sus discos, con formato Digipack de cubierta de cartón y libreto interior (bilingüe + idioma original), quieren acercarse a una obra de arte total.