pneumamusic

PN 1040 CAUTIVO DE AMOR, EGIPTO

PN 1040 CAUTIVO DE AMOR, EGIPTO

No se pudo cargar la disponibilidad de retiro

Índice

Índice

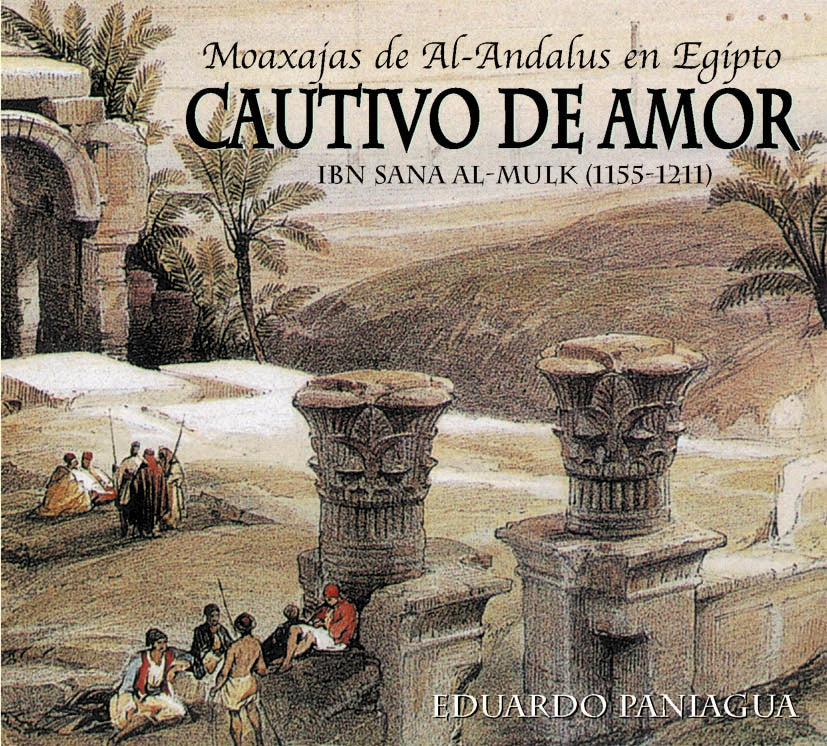

CAUTIVO DE AMOR

MOAXAJAS DE AL-ANDALUS EN EGIPTO

MUWASHSHAHAT FROM AL-ANDALUS IN EGYPT

CAPTIVE OF LOVE

IBN SANA AL-MULK (1155-1211)

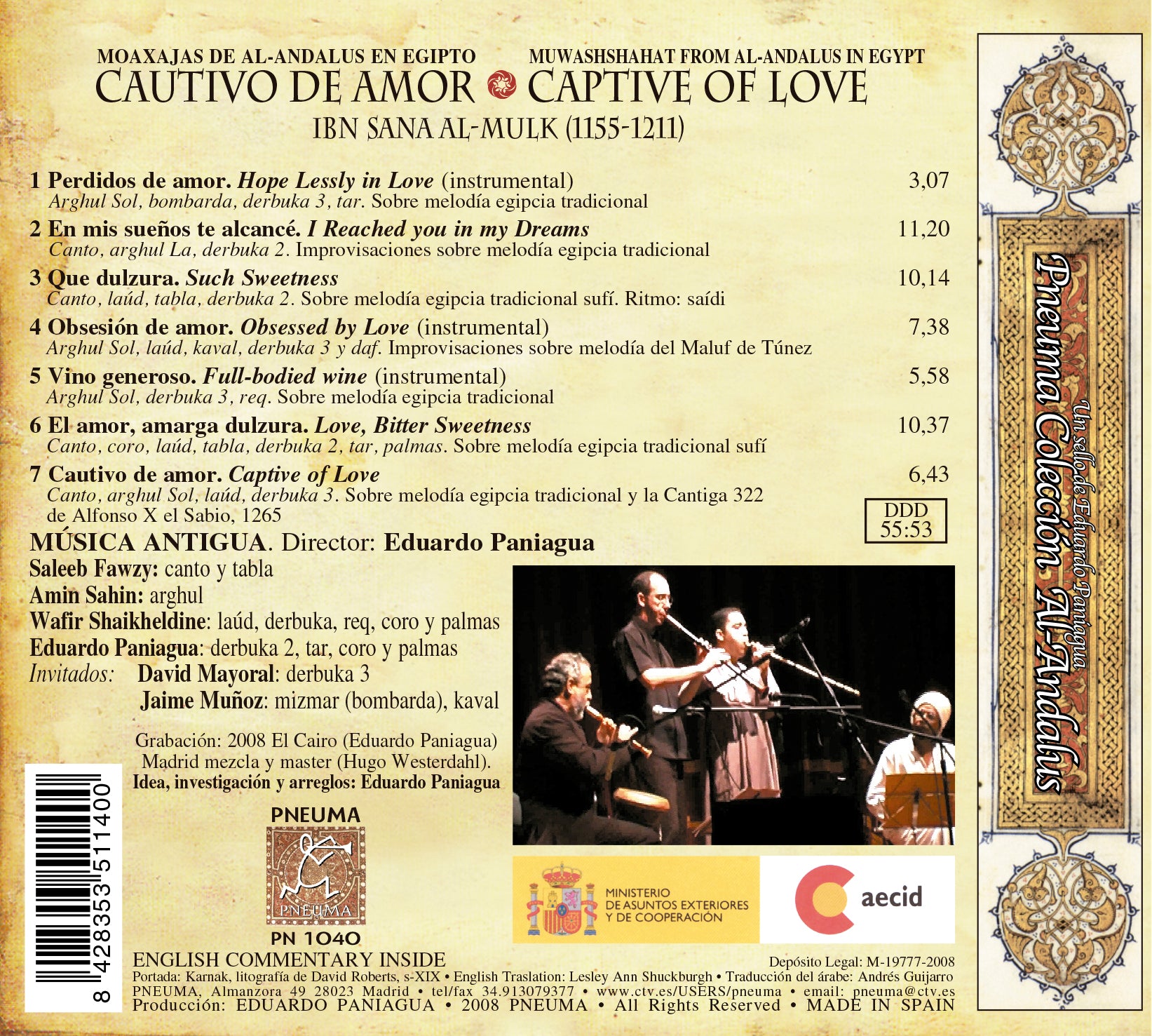

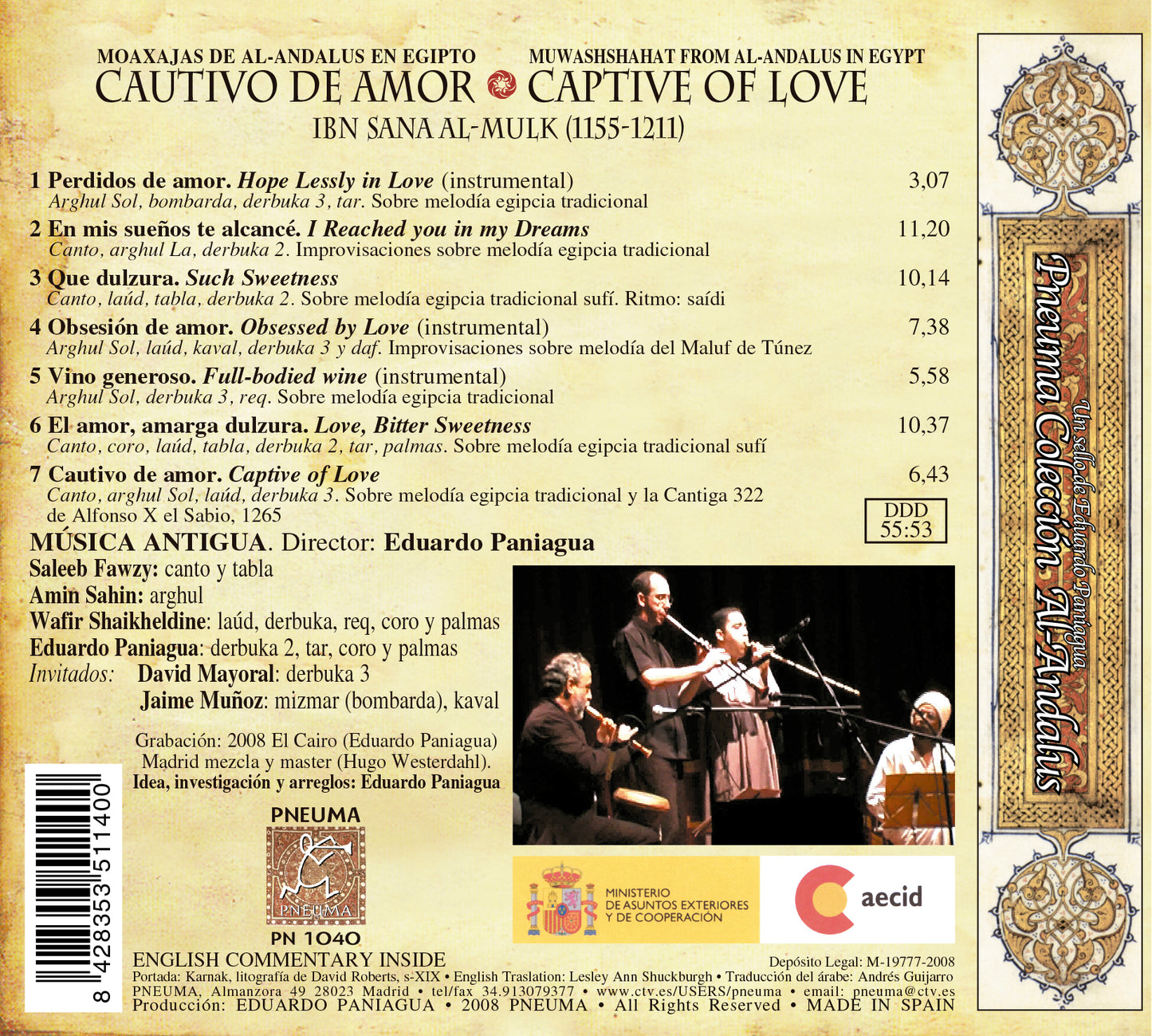

MÚSICA ANTIGUA. Director: Eduardo Paniagua

Saleeb Fawzy: canto y tabla

Amin Sahin: arghul

Wafir Shaikheldine: laúd, derbuka, req, coro y palmas

Eduardo Paniagua: derbuka 2, tar, coro y palmas

Invitados: David Mayoral: derbuka 3

Jaime Muñoz: mizmar (bombarda), kaval

1 Perdidos de amor. Hope Lessly in Love (instrumental) 3,07

Arghul Sol, bombarda, derbuka 3, tar. Sobre melodía egipcia tradicional

2 En mis sueños te alcancé. I Reached you in my Dreams 11,20

Canto, arghul La, derbuka 2. Improvisaciones sobre melodía egipcia tradicional

3 Que dulzura. Such Sweetness 10,14

Canto, laúd, tabla, derbuka 2. Sobre melodía egipcia tradicional sufí. Ritmo: saídi

4 Obsesión de amor. Obsessed by Love (instrumental) 7,38

Arghul Sol, laúd, kaval, derbuka 3 y daf.

Improvisaciones sobre melodía del Maluf de Túnez

5 Vino generoso. Full-bodied wine (instrumental) 5,58

Arghul Sol, derbuka 3, req. Sobre melodía egipcia tradicional

6 El amor, amarga dulzura. Love, Bitter Sweetness 10,37

Sobre melodía egipcia tradicional sufí

Canto, coro, laúd, tabla, derbuka 2, tar, palmas.

7 Cautivo de amor. Captive of Love 6,43

Canto, arghul Sol, laúd, derbuka 3.

Sobre melodía egipcia tradicional y la Cantiga 322 de Alfonso X el Sabio, 1265

Grabación: 2008 El Cairo (Eduardo Paniagua)

Madrid mezcla y master (Hugo Westerdahl).

Idea, investigación y arreglos: Eduardo Paniagua

Portada: Karnak, litografía de David Roberts, s-XIX

Producción: EDUARDO PANIAGUA • 2008 PNEUMA • MADE IN SPAIN

Descripción

Descripción

MOAXAJAS DE AL-ANDALUS EN EGIPTO

La moaxaja y su secuela el zéjel son invenciones poéticomusicales españolas que nacieron en Andalucía y viajaron hasta Oriente, donde fueron objeto de análisis teórico, preceptiva y retórica.

Muqaddam Ibn Mu´afa al-Qabrí (m. 911-912), el ciego de Cabra, inventó la moaxaja, unos 50 años después de la muerte de Ziryab, el creador de la Escuela musical andalusí. Fue imitado por Abd al-Rabbini (m. 940) (El collar único), pero según Ibn Jaldún (1332-1406) sus obras fueron completamente olvidadas. De nuevo resucitó la moaxaja con Ubada Ibn Ma´al Samá (m.1040) y Ubada al-Qazzaz de Almería. Alcanzó su Edad de Oro durante el tiempo de los Almorávides, estrechamente ligada a la música, con el Ciego de Tudela (m.1130), Ibn Labbana (m.1113), Ibn Báya (m.1138) e Ibn Baqí (m.1145). Bajo los Almohades siguió floreciendo con Ibn Zuhr (m.1198) e Ibn Sahl (m.1251).

Este género poético y musical se divulgó en Oriente en el siglo XII durante el periodo Fatimí y Ayyubí, alcanzando su apogeo en Egipto con Ibn Sana al-Mulk (1155-1211) y sus discípulos: al-Fadil, Ibn Nabih, Ibn Wakil, Ibn Danyal, Ibn Nubata y Safadí. Este éxito de la moaxaja fue consecuencia de la revolución musical que produjo la canción basada sobre este género poético.

IBN SANA AL-MULK (1155-1211)

Ibn Sana al-Mulk, autor del “Dar at-Tiraz”, La casa del brocado, nació en El Cairo en 1155. Con buena formación religiosa y literaria, se convirtió en el centro de un grupo de escritores que cantaron a Saladino. Viajó por Siria, llevando una vida acomodada hasta su muerte también en El Cairo en 1211. Se entusiasmó con la moaxaja de al-Andalus y fue capaz de codificarla, lo cual le ha dado su fama histórica.

“ Entre las cosas que los antiguos dejaron por descubrir a los modernos, que los habitantes de Occidente han vencido a los de Oriente, figuran las moaxajas, sal de la época, Babel de la magia, ámbar de Sihr, áloe de la India, vino de Qufs, tíbar del Algarbe, patrón de entendimientos, balanza de inteligencias y quintaesencia suprema, puesto que a la par deleitan y emocionan, incitan a su imitación y hacen desesperar de lograrla, seducen y atraen, vacían de cuidados y ocupan el ocio, acompañan y ahuyentan.

Merced a ellas, el Occidente se ha convertido en Oriente, pues por aquel horizonte surgieron y aquel aire iluminaron, haciendo que los habitantes de las tierras occidentales vinieran a ser los mas ricos de los hombres, con haberse hecho dueños de este tesoro que les reservó el Destino y de esa mina antes desatendida por la humanidad”.

Del “Dar at-Tiraz” se conocen dos manuscritos, uno en Leiden y otro en El Cairo. Yawdat Al-Rikabi, en Damasco 1949, hizo una edición crítica, la cual sirvió de base para la traducción realizada por Emilio García Gómez “Estudio de Dar at-Tiraz, preceptiva egipcia de la muwashshaha”, Al-Andalus, XXVII, Madrid 1962.

“Dar at-Tiraz” consta de una primera parte con la exposición teórica, una segunda que incluye una antología de 34 moaxajas andalusíes y por último, 35 moaxajas del propio autor. La primera parte es a la que los estudiosos han dado más importancia, pero nuestro trabajo se ha basado en la tercera parte, cantando por primera vez fragmentos de los poemas de al-Mulk.

La traducción del “Dar at-Tiraz” de García Gómez omite la de los poemas de Al-Mulk. Estas traducciones al español se han encargado expresamente al arabista Andrés Guijarro para este CD.

“En la flor de mi vida y de mis verdes años me prendé de ellas (las moaxajas), las amé con pasión, las oí a menudo, me las aprendí de memoria, las estudié a fondo, penetré en sus secretos, me asomé a sus senos, las revolví por dentro y por fuera, abracé a sus vírgenes y a sus matronas, buceé en pos de sus perlas escondidas, y no contento con las noticias sabidas, me interné en sus ocultos repliegues. Llegué a comprender que su conocimiento es estímulo de la razón y rectificación del entendimiento, así como su ignorancia es ofensa del carácter y perversión de la mente”.

La música de estas canciones no se ha conservado en la tradición oral por lo que hemos buscado melodías egipcias tradicionales, tanto del ambiente místico sufí como de la tradición popular, interpretadas con el arghul, clarinete doble primitivo. Se han evitado pues las melodías andalusíes del Magreb, incluyendo sin embargo una melodía medieval hispana cuyo texto original es un poema zejel (Cantigas de Alfonso X el Sabio, 1275), herederas de la tradición musical de al-Andalus, y que nos sirvieron de experimento inicial para analizar las posibilidades y escalas del fascinante arghul, al que al-Mulk considera imprescindible para interpretar las moaxajas.

Las moaxajas de al-Mulk son imitación formal de las de aquellos poetas andalusíes que utiliza como ejemplo para su exposición teórica.

“Y ahora ha llegado el momento de citar y exponer las moaxajas de las que he sacado los anteriores ejemplos, añadiéndoles como apéndice mis propias moaxajas. (que son 35), de tal suerte que a cada una de las antiguas corresponda otra mía, hecha conforme a su patrón y según el mismo molde en cuanto al numero de aqfál y abyat (estrofas y versos). Por lo demás mis moaxajas no son sino como la sombra y espectro de las antiguas y reconozco que quedan muy por debajo de la perfección de éstas. Si las he insertado es porque, como dije, en la “Casa del brocado” ha de haberlos tanto de seda como de oro, lo mismo de un sólo color que son orlas de otro. Estas moaxajas mías, que inserto, son de seda y de un sólo color. Pero, aunque no tengan orlas, despliégalas, considéralas con atención, y disculpa a este hermano tuyo que no nació en al-Andalus, ni se crió en el Magreb, ni vivió en Sevilla, ni afincó en Murcia, ni pasó por Mequinez, ni escuchó el órgano, ni alcanzó la corte de Mu´tamid ni la de Sumadih, ni trató al Ciego de Tudela, ni a Ibn Baqi, ni a ´Ubada, ni al Husri, ni encontró maestro con el que adiestrarse en esta ciencia, ni autor del que aprender este arte”.

EL ARGHUL

El arghul, quourma o zummará, es un tipo de clarinete doble primitivo. El nombre proviene del urgün (órgano o instrumento tradicional) y consta de un doble cuerpo de caña con lengüeta simple; una caña melódica con 6 orificios “badan” y la otra, sin orificios a modo de bordón, que puede cambiar de nota, alargándose la caña al añadir extensiones. Para su ejecución se requiere la técnica de la respiración continua circular. Este instrumento egipcio data de la V Dinastía faraónica, 2.700 a C.

Variante del arghul en la España medieval cristiana es el albogue, “al buq” (cuerno, trompeta); clarinete popular de caña o madera con uno o dos tubos y con un pabellón final de cuerno. En la actualidad aún existen en la Península Ibérica al menos dos descendientes de este instrumento con final de cuerno: la gaita serrana de Madrid, de un solo tubo de madera, y la alboka vasca con dos cañas unidas por un yugo o soporte de madera, una con cinco orificios y otra con tres.

Dice al-Mulk, “La mayor parte (de las melodías de las moaxajas) están basadas en la composición del órgano (argun) y cantarlas acompañadas de otro instrumento es como cosa prestada y por extensión.” Aunque los expertos arabistas y musicólogos, citando este texto, piensen en el órgano del siglo XII (órgano de mano o positivo traído sin duda de Bizancio), como instrumento para acompañar las moaxajas, creemos, por esta y otras citas contemporáneas, que se está hablando del arghul y sus variantes. Ello nos ha conducido a elegir el arghul de El Cairo como instrumento básico para interpretar estos poemas de Ibn Sana al-Mulk.

Según su contemporáneo andalusí al-Tifasi (1184-1253): “Entre los instrumentos más estimados por las gentes de al-Andalus se encuentran el ´ud (laúd), al-zamr (lengüeta, qourma, zummara o arghul), al-nai (flauta oblicua), al-duff (pandero) y al-siz (crótalos). También utilizan la ruta (rota) y está bien considerado el rabab. No obstante el instrumento más noble y refinado es al-buq (cuerno, trompeta), que por la dulzura y delicadeza de su timbre conviene perfectamente al acompañamiento de la danza y el canto”.

El al-buq es descrito como “un tipo de zamr (clarinete primitivo) bastante grande y provisto de una serie de piezas que se ensamblan unas en otras. Este instrumento produce sonidos de una gran belleza y de conmovedora expresividad, siendo el más completo y adecuado para las festividades y para el acompañamiento del canto y de la danza”.

Según Ibn Sa´id (1214-1286) y más tarde Ibn Jaldún (1332-1406), al-buq es el instrumento que acompaña a los zéjeles sufíes. Sequndí (m.1231) ofrece una lista de los instrumentos utilizados en la Sevilla del siglo XII: “al-jayal (laúd), al-kuray, al-´ud, al-ruta (rota), al-rabab, al-qanun, al-mu´nis (¿laúd?), al-kutayra (kuitra), al-fanar (¿?), al-zulami (zalami), as-saqra (¿flauta doble?), al-nura (lengüeta), al-buq (albogue)”.

LA MÚSICA DE LAS MOAXAJAS

Ibn Saná al-Mulk nos advierte la importancia de la música y el ritmo con que se cantan las moaxajas. Explica que un método utilizado consistía en componer primero la melodía y luego adaptar el texto respetando el ritmo musical, sin preocuparse de la métrica poética.

“No tienen más prosodia que la música, ni más ritmo que la ejecución instrumental, ni más pies que las clavijas de los instrumentos, ni más sílabas que las cuerdas de estos. Sólo por este procedimiento de tocarlas se distingue lo medido de lo no medido y lo cojo de lo sano”.

En ocasiones hay que rellenar de sílabas sin sentido para completar la melodía (taratín, ye la la,). En definitiva, dice que en las moaxajas que no se ajustan a la prosodia clásica, son la melodía y los acentos del ritmo los que marcan si una moaxaja es perfecta o defectuosa.

“La balanza de la música hace distinguir la buena moaxaja de la mala y lo entero de lo cojo, pues hay pasajes que la pura percepción tiene por cojos e incluso rotos, y sin embargo, al ser cantados, la música suelda en ellos la supuesta fractura y cura la falsa dolencia, tornando sano lo que parecía dañado y alisando lo que se tenía por abrupto, sin que en todo ello se mueva una palabra”.

The muwashshah and its sequel the zejel are Spanish poetic-musical inventions that were born in Andalusia and travelled to the Orient, where they became the object of theoretical, preceptive and rhetorical analysis.

Muqaddam Ibn Mu’afa al-Qabrí (d.911-912), know as the blind man of Cabra, invented the muwashshah some 50 years after the death of Ziryab, the creator of the Andalusi musical School. The muwashshah was copied by Abd al-Rabbini (d.940) (The Only Necklace), but according to Ibn Jaldun his works were completely forgotten. The muwashshah re-emerged with Bada Ibn Ma’al Samá (d.1040) and Ubada al-Qazzaz of Almeria. But it was at the time of the Almoravids, when it was closely linked to music, that it achieved its Golden Age, with the Blind Man of Tudela (d.1130), Ibn Labbana (d.1113), Ibn Baya (d.1138) and Ibn Baqi (d.1145). Under the Almohads it continued to flourish with Ibn Zuhr (d.1198) and Ibn Sahl (d.1251).

This poetic and musical genre spread through the Orient in the 12th century during the Fatimi and Ayyubi period, reaching its height in Egypt with Ibn Sana al-Mulk (1155-1211) and his disciples: al-Fadil, Ibn Nabih, Ibn Wakil, Ibn Danyal, Ibn Nubata and Safadí.

The success of the muwashshah was the consequence of the musical revolution created by the song based on this poetic genre.

IBN SANA AL-MULK (1155-1211)

Ibn Sana al-Mulk, author of the “Dar at-Tiraz”, The House of Brocade, was born in Cairo in 1155. With good religious and literary training, he became the centre of a group of writers that sang to Saladin. He travelled around Syria, living a comfortable life until his death also in Cairo in 1211. He was enthusiastic about the Al-Andalus muwashshah and managed to classify it, which has given him his historical fame.

“Among the things the ancients left to be discovered by the moderns and that the inhabitants of the West have conquered from those of the East, are the muwashshahat, the salt of the era, Babel of magic, amber of Sihr, aloe of India, wine of Qufs, pure gold of the Algarbe, code of understanding, balance of intelligences and supreme quintessence, since they are at once delightful and moving, they provoke imitation and make you desperate to succeed, they seduce and attract, they empty your cares and fill you with leisure, they accompany and repel.

Thanks to them, the West has become the East, since they arose on the horizon of the former and illuminated its air, making the inhabitants of the Western lands become the richest of men, making them the owners of this treasure that Destiny set aside for them and of this mine that was until then unattended by humanity”.

There are two known manuscripts of the “Dar at-Tiraz”, one in Leiden and the other in Cairo. In Damascus in 1949 Yawdat Al-Rikabi, produced a critical edition that served as the basis for the translation by Emilio García Gómez “Study of Dar at-Tiraz, Egyptian Prececpt of the Muwashshaha”, Al-Andalus, XXVII, Madrid 1962.

“Dar at-Tiraz” consists of a first part containing a theoretical exposition and a second part with an anthology of 34 Andalusi muwashshahat and lastly, 35 muwashshahat by the author. Scholars have attributed most importance to the first part, but this work is based on the third part, and fragments from the poems by al-Mulk are sung for the first time. The translation of the “Dar at-Tiraz” by García Gómez does not include the translation of the poems by Al-Mulk, which has been specifically commissioned from the Arabist Andrés Guijarro for this CD.

“In the prime of my life and in my salad days I fell in love with them (the muwashshahat), I loved them with passion, I listened to them often, I learned them by heart, I studied them in detail, I penetrated their secrets, I peered into their breasts, I stirred them up inside and out, I embraced their virgins and their matrons, I swam underwater in search of their hidden pearls, and not content with what I discovered, I delved into their hidden folds. I managed to understand that knowledge of them stimulates reason and corrects understanding, and that ignorance of them is an offence to the character and perversion of the mind”.

The music to these songs has not been preserved in the oral tradition and so we have looked for traditional Egyptian melodies, both in the mystic Sufi world and in the popular tradition played on the arghul. We have therefore refrained from using Andalusi melodies from the Maghreb, but have included some Hispanic medieval melodies used for the zejel poems (Cantigas of Alfonso X the Wise), heirs of the Al-Andalus musical tradition. These provided us with an initial experiment to analyse the possibilities and scales of the fascinating arghul, a primitive double-pipe clarinet, which al-Mulk considers essential to play the muwashshahat.

Al-Mulk’s muwashshahat are examples of formal imitation of the ones written by the Andalusi poets that he uses for theoretical exposure.

“And now the moment has come to quote and expound on the muwashshahat from which I have taken the previous examples, adding them as an appendix to my own muwashshahat (of which there are 35), in such a way that one of mine corresponds to each one of the old ones, written following its pattern and using the same mould with regard to the number of aqfál and abyat (verses and lines). Otherwise my muwashshahat are no more than the shadow and spectre of the old ones and I recognise that they are very inferior to the perfection of these. If I have inserted them it is because, as I said, in the “House of Brocade” there should be ones of both silk and gold, just as there are ones of only one colour and ones that have borders of another. These muwashshahat of mine, that I have inserted, are of silk and only one colour. But, although they do not have borders, spread them out, look at them carefully, and forgive this brother of yours who was not born in Al-Andalus, or brought up in the Maghreb, who did not live in Seville, or stay in Murcia, or go through Mequinez, or listen to the organ, or reach the court of Mu’tamid or that of Sumadih, or meet the Blind Man of Tudela, or Ibn Baqi, or ‘Ubada, or al Husri, or a master with whom to perfect this science, or an author from whom to learn this art.”

THE ARGHUL

The arghul, quourma or zummara is a type of primitive double clarinet. The name comes from urgün (organ or traditional instrument) and consists of a double pipe with a single reed. One is a melodic pipe with 6 holes “badan” and the other, without holes is like a drone pipe, to which extensions can be added to alter the pitch of the drone. To play it the circular breathing technique must be used. This Egyptian instrument dates back to the 5th Pharaonic dynasty, 2700 years B.C.

A variant of the arghul in medieval Christian Spain is the albogue, “al buq” (horn, trumpet): a popular cane or wooden clarinet with one or two pipes and a bell at the end made of horn. Nowadays in the Iberian Peninsula there are still two descendants of this instrument with the end made of horn, the gaita serrana in Madrid, with just one wooden pipe, and the Basque alboka with two pipes one with five holes and the other with three, joined by a yoke or wooden support.

Al-Mulk says, “Most (of the melodies of the muwashshahat) are based on organ (argun) compositions and to sing them to another instrument is like doing something on loan and by extension.” Although Arab experts and musicologists, quoting this text, think of the organ of the 12th century (hand organ or positive organ, no doubt brought from Byzantium), as the instrument to accompany the muwashshahat, we think that this and other contemporary quotes refer to the arghul and its variants. This is why we chose the arghul from Cairo as the basic instrument to play these poems by Ibn sana al-Mulk.

According to an Andalusi contemporary (1184-1253) “Among the instruments most highly esteemed by the peoples of Al-Andalus are the ‘ud (lute), al-zamr (reed, qourma, zummara or arghul), al-nai (end-blown flute), al-duff (large tambourine), and al-siz (castanets). They also use the ruta (rota – a 17 string zither) and the rabab is highly regarded. However the most noble and refined instrument is the albuq (horn, trumpet) whose sweetness and delicate timbre make it perfect to accompany dance and song”. The al-buq is described as “quite a large type of zamr (primitive clarinet) that has a series of pieces that fit together. This instrument produces very beautiful and highly moving sounds, and is the most complete and adequate for festivals and to accompany song and dance”.

According to Ibn Sa’id (1214-1286) and later Ibn Jaldun (1332-1406) al-buq is the instrument that accompanies the Sufi zejels. Sequndi (d.1231) offers a list of the instruments used in Seville in the 12th century: “al –jayal (lute), al-kuray, al-‘ud, al-ruta (rota), al-rabab, al-qanun, al-mu’nis (lute?), al-kutayra (kuitra) al-fanar, al-zulami (zalami), as-saqra (double flute?), al-nura (reed), al-buq (albogue).

THE MUSIC OF THE MUWASHSHAHAT

Ibn Sana al-Mulk points out the importance of the music and rhythm to which the muwashshahat are sung. He informs us that one method used consisted of composing the melody first and then adapting the text respecting the musical rhythm, without worrying about the poetic metre.

“They do not have more prosody than the music, or more rhythm than the instrumental performance, or more feet than the pegs of the instruments, or more syllables than their strings. Only by playing them can the well-measured be distinguished from the badly-measured and the lame from the healthy”.

Sometimes a melody has to be filled in by adding syllables without any sense (tatatum, la, la, la). In short, he says that in the muwashshahat that do not adjust to classical prosody it is the melody and the rhythmic accents that determine whether a muwashshah is perfect or defective.

“The musical balance distinguishes between a good muwashshah and a bad one, between the whole and the incomplete, since there are passages that pure perception counts as lame and even broken, yet when they are sung, the music knits the supposed fracture and cures the false pain, healing what appeared to be damaged and smoothing out what seemed to be abrupt, without moving a single word”.

Eduardo Paniagua

Compartir

-

Envío gratis en pedidos mayores a 50 €.

Entrega en 5-7 días laborables para pedidos en España, en el caso de envíos fuera de España el tiempo de envío podría ser algo mayor.

-

Todo el trabajo de Pneuma Music se ha realizado en España.

Música medieval española inédita hasta el momento. Sus discos, con formato Digipack de cubierta de cartón y libreto interior (bilingüe + idioma original), quieren acercarse a una obra de arte total.