pneumamusic

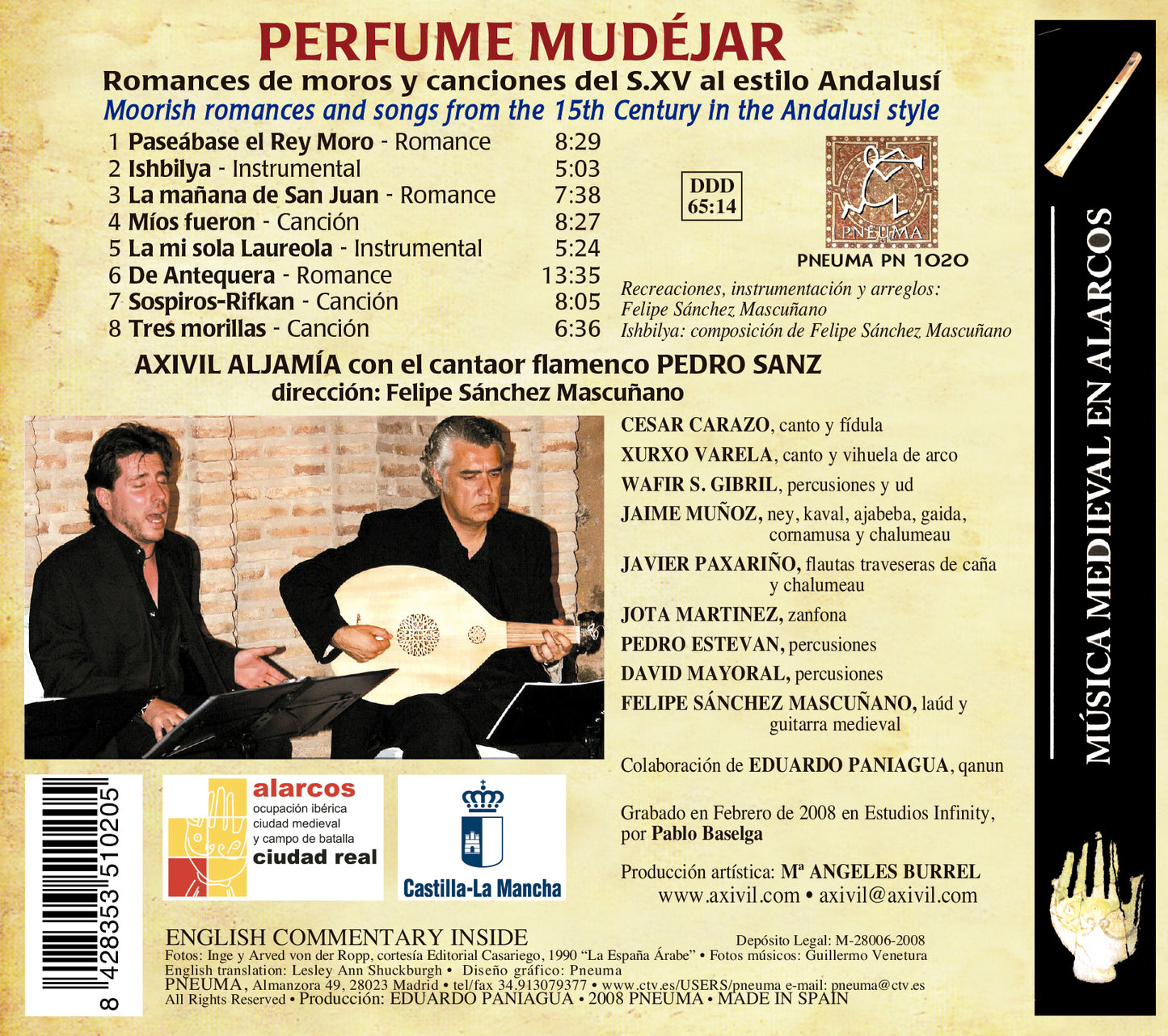

PN 1020 PERFUME MUDÉJAR. Romances de moros y canciones del S.XV al estilo Andalusí

PN 1020 PERFUME MUDÉJAR. Romances de moros y canciones del S.XV al estilo Andalusí

No se pudo cargar la disponibilidad de retiro

Índice

Índice

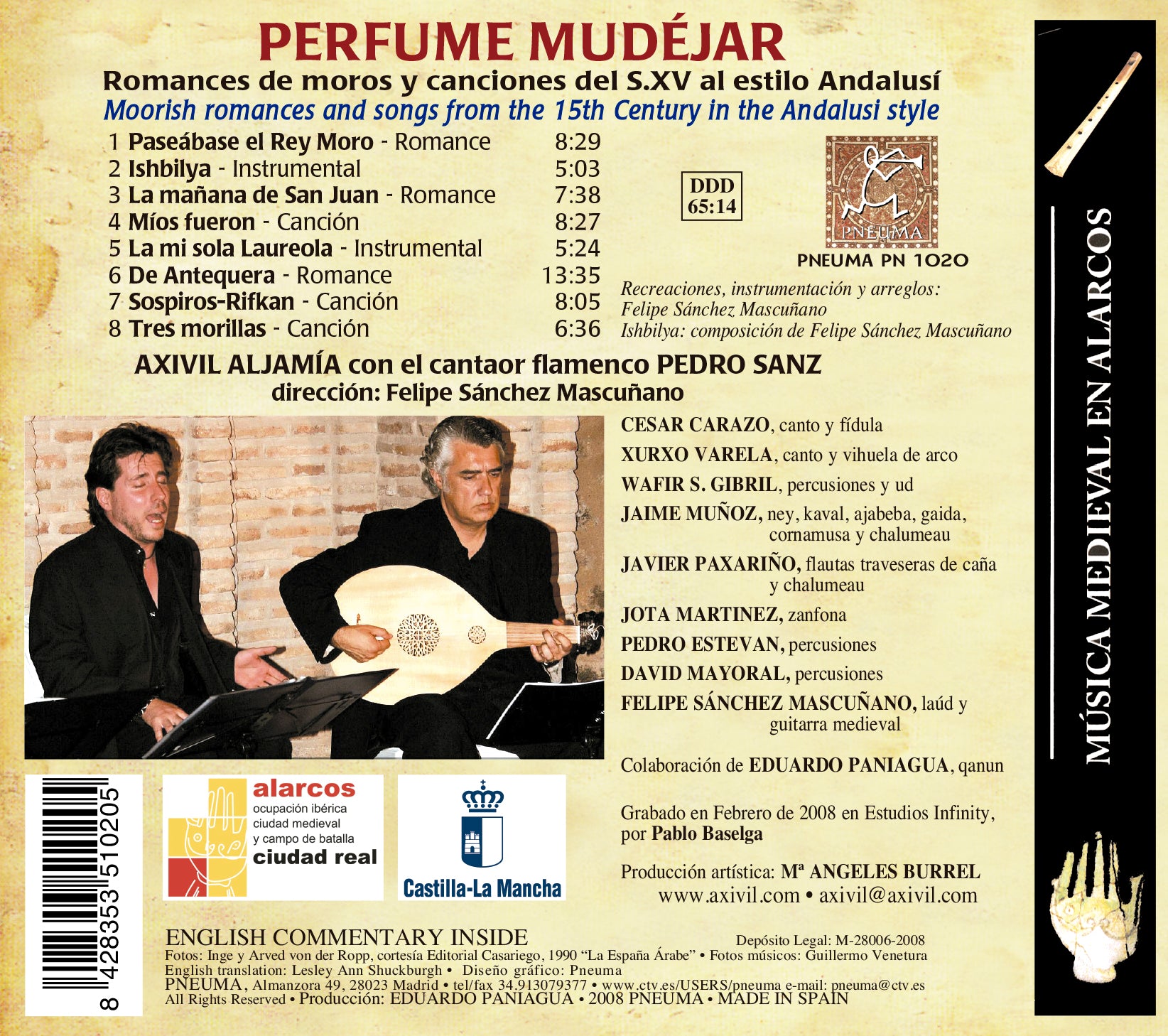

PERFUME MUDÉJAR

Romances de moros y canciones del S.XV al estilo Andalusí

Moorish romances and songs from the 15th Century in the Andalusi style

AXIVIL ALJAMÍA con el cantaor flamenco PEDRO SANZ

Dirección: Felipe Sánchez Mascuñano

Cesar Carazo: canto y fídula

Xurxo Varela: canto y vihuela de arco

Wafir S. Gibril: percusiones y ud

Jaime Muñoz: ney, kaval, ajabeba, gaida, cornamusa y chalumeau

Javier Paxariño: flautas traveseras de caña y chalumeau

Jota Martinez: zanfona

Pedro Estevan: percusiones

David Mayoral: percusiones

Felipe Sánchez Mascuñano: laúd y guitarra medieval

Colaboración de Eduardo Paniagua: qanun

1 Paseábase el Rey Moro - Romance 8:29

Relata la toma de Alhama en 1482. La letra y la melodía deben de ser de una fecha cercana a los hechos y está recogida en los libros de vihuela de Luis Narváez (1538) y de Diego Pisador (1552).

The story of the taking of Alhama in 1482. The words and the melody must date from around the time of the events, and the song is included in the vihuela books by Luis Narvaez (1538) and Diego Pisador (1552).

2 Ishbilya - Instrumental 5:03

Está compuesta por Felipe Sánchez Mascuñano a modo de las introducciones instrumentales andalusíes.

Composed by Felipe Sánchez Mascuñano in the style of the Andalusi instrumental introductions.

3 La mañana de San Juan - Romance 7:38

Relata la toma de Antequera en 1410. La letra y la melodía deben de ser también cercana al acontecimiento. Sobre ella Diego Pisador compuso una canción a 4 voces.

The story of the taking of Antequera in 1410. The words and melody must also date from about the same time as the events. Diego Pisador composed a song in 4 parts based on this story.

4 Míos fueron - Canción 8:27

Hay tres versiones de esta canción en el Cancionero Musical de Palacio, siglo XV. Dos de Mondejar y una de Ponce.

There are three versions of this song in the 15th Century Palace Songbook. Two by Mondejar and one by Ponce.

5 La mi sola Laureola - Instrumental 5:24

Es también del Cancionero Musical de Palacio. Versión de la canción La mi sola de Ponce.

This piece is also from the Palace Songbook. Version of the song La mi sola by Ponce.

6 De Antequera - Romance 13:35

Relata los mismos hechos que La Mañana de San Juan. La melodía fue usada por Cristóbal Morales que compuso una pieza a 4 voces con ella. Fue puesta en vihuela por Miguel de Fuenllana (libro de 1554).

The story of the same events as The Morning of St. John. The melody was used by Cristóbal Morales to compose a piece in 4 parts. It was adapted for vihuela by Miguel de Fuenllana (book from 1554).

7 Sospiros -Rifkan - Canción 8:05

Es de Badajos y está en el Cancionero Musical de Palacio. Para el final, se ha añadido la saná, “Rifkan”, de la nuba “Ushshaq”, andalusí de Marruecos.

This piece from Badajos is also in the Palace Songbook. The saná “Rifkan”, from the Andalusi nawbah “Ushshaq” from Morocco, has been added for the ending.

8 Tres morillas - Canción 6:36

La versión utilizada es la original anónima del Cancionero Musical de Palacio.

The version used is the original anonymous one from the Palace Songbook.

Grabado en Febrero de 2008 en Estudios Infinity por Pablo Baselga

Recreaciones, instrumentación y arreglos: Felipe Sánchez Mascuñano

Ishbilya: composición de Felipe Sánchez Mascuñano

Producción: EDUARDO PANIAGUA • 2008 PNEUMA • MADE IN SPAIN

COMENTARIOS

Este CD cubre perfectamente la ideología y objetivos de Pneuma, una colección de música relacionada con la historia de España que, junto al rigor y la documentación, tenga la valentía y la libertad del intérprete para hacer viva la música antigua. Agradezco a Felipe Sánchez Mascuñano la propuesta de que edite su trabajo Perfume Mudéjar en Pneuma, y que además me proponga como intérprete de qanun en su composición Ishbilya.

El rastreo de arabistas, romanistas, musicólogos y músicos para vislumbrar la riqueza de los influjos de las culturas musicales árabes y judías españolas desde el medievo al romanticismo va en aumento. Grupos musicales españoles como Atrium Musicae de Gregorio Paniagua (1967-82), Cálamus (1980-1995), Mudéjar de Begoña Olavide, desde 1993 y mi propio grupo Música Antigua desde 1994, han experimentado la interpretación de este mundo fronterizo.

Axivil de Felipe Sánchez con este trabajo da un paso más en la re-visión de las fuentes musicales de los Cancioneros de los siglos XV y XVI, bajo la influencia de la música andalusí-magrebí y del oriente musulmán.

Por ello felicito a Felipe y daré seis motivos de mi valoración positiva de su resultado:

1- La importancia capital del ritmo, tomada del mundo andalusí.

2- La riqueza tímbrica, la expresividad y el colorido de la instrumentación, junto a la ornamentación y a los momentos de libre improvisación.

3- La elección de la voz solista, cante natural mediterráneo, experimentado en la riqueza técnica de la tradición del flamenco, que se aleja voluntariamente de la educación vocal posterior al tiempo del barroco.

4- Conjunción del solista con el resto de voces en una polifonía acertada y sorprendentemente natural.

5- La fuerza expresiva de los instrumentistas, donde se descubre técnica y experiencia (tablas) en otros muchos tipos de estilo musical.

6- Los arreglos musicales de Felipe que hacen viva la lectura de esta selección de conocidas partituras antiguas.

Eduardo Paniagua

Descripción

Descripción

PERFUME MUDÉJAR

Puedo jurar que no es a propósito, pero todos los repertorios de AXIVIL acaban siendo difíciles de encuadrar y en los anaqueles de las tiendas se acaban encontrando nuestros discos.... en apartados y bajo epígrafes que ni a mí mismo ni a muchos que me lo han dicho se nos habría ocurrido buscarlos. Nunca me he jactado de ello y no quiero que lo parezca - más bien es un problema - pero es un hecho que grita a voces que el patrimonio musical español está lleno de resquicios y vericuetos por donde se destila arte a raudales pero que resulta difícil de catalogar con las categorías y nomenclaturas del siglo XXI.

En España se distingue lo mudéjar en la arquitectura, en las maravillosas artes menores, en la jardinería, en la gastronomía... hasta el idioma castellano incorpora cientos de vocablos que vienen del árabe, por no hablar de los topónimos... pero ¿qué ocurre con la música? Pues no tenemos otro remedio que indagar en las fuentes cristiano-occidentales de nuestro pasado y en lo que queda de la música que hacían los españoles de cultura musulmana de nuestra Edad Media y que, en diversas oleadas, fueron desplazándose al norte de África, es decir, en la música andalusí, conservada por tradición oral en Argelia, Túnez y, sobre todo, en Marruecos.

No ha sido difícil seleccionar un repertorio que nos llevara a ese misterioso mundo musical mudéjar. Porque ya en las mismas melodías, ritmos, giros interválicos y ""aire"" encontramos un PERFUME que en romances como La Mañana de San Juan, Paseabase el rey Moro, De Antequera sale el Moro o Tres Morillas m'enamoran en Jaen es inequívoco. Un PERFUME que sólo en canciones hechas en nuestra península encontramos, aunque sean canciones incardinadas perfectamente en la tradición musical cristiano-occidental.

¿En qué proporción está presente la cultura hispano-musulmana en estas canciones? Pues no lo sé ni pretendo llegar a saberlo. Sólo puedo decir que, para un músico, mezclar sensaciones musicales, estilísticas y hecho históricos produce una iniciativa musical y estilística de manera casi inconsciente... no hay más que atar cabos y tener ganas de hacer música.

Cómo hacer que ese perfume se huela de verdad y no sea una experiencia íntima en mi mesa de trabajo fue el siguiente paso. El aspecto del sonido mudéjar me lo imaginé parecido al de las actuales orquestas andalusíes de Marruecos, pero con la pertinente mezcla de instrumentos árabes y occidentales que existía en la España del siglo XV. De hecho, en las pocas representaciones que conozco de músicos moriscos, éstos llevan en sus manos instrumentos cristianos y, al revés, abundan pinturas y frescos de ángeles músicos que tocan instrumentos plenamente árabes.

El siguiente paso era pensar en el tipo de canto que había que utilizar. Y, escuchando a diferentes cantores andalusíes, es evidente que la técnica de emisión de la voz, el ornamento y, finalmente, el concepto mismo de canto los tenemos, idénticos o muy parecidos, en el Cante Flamenco...Otro cabo que había que atar, pero había más razones para acudir a la ayuda del Cante Flamenco. Que exista una música como el Flamenco, nacida en un país occidental y en plena y viva actividad en el siglo XXI es un hecho portentoso. No sé qué parentesco pueda tener con lo que se cantaba en la España de finales del siglo XV -si se llegase a saber, nos lo dirían los flamencólogos- pero la naturalidad con la que el cante suena en este trabajo es una de las cosas que me producen más satisfacción como músico.

Por otro lado, no encuentro mejor manera de transmitir el dramatismo comprimido de esas joyas literarias que son los romances fronterizos si no es acudiendo a la rotunda expresividad del Cante Flamenco. Además, cuando se oyen expresiones como ""desde la puerta de Elvira hasta la de Bibarrambla"" o ""que de la Alhambra salía"" o ""paseabase el rey moro"" saliendo de la boca de un cantaor flamenco, esas expresiones tienen siempre un sabor irrenunciable.

No sé si estas canciones sonaron así o de forma parecida a finales del siglo XV pero, además de disfrutar de su hermosura musical, también me emociona el pensar que podrían haber sonado más o menos así.

Finalmente, quiero agradecer a todos y cada uno de los músicos no ya su maestría -más que demostrada- sino su entrega. Especialmente a Pedro Sanz, nuestro cantaor, al que sacamos de su órbita para llevarlo a otra galaxia cercana pero inexplorada. Un viaje que ha necesitado mucho trabajo y esfuerzo y Pedro ha solucionado con su mejor equipaje: su arte. También agradecer a Pablo Baselga, nuestro ingeniero de sonido, el despliegue de buen gusto -que tiene mucho- en esta grabación. A Eduardo Paniagua que ha puesto toda su experiencia -que es mucha- a nuestro servicio y a Angeles Burrel, nuestra productora, que ha estado detrás de todas las decisiones -que han sido muchas- que se han tenido que tomar para poner en pie este proyecto.

Felipe Sánchez Mascuñano

COMENTARIOS

I would like to thank Felipe Sánchez Mascuñano for proposing to release his work Perfume Mudéjar on Pneuma, and also for approaching me to play the qanun on his composition Ishbilya. This CD embraces the ideology and objectives of Pneuma perfectly, as a collection of music related to the history of Spain that brings the ancient music alive through not only rigour and documentation, but also the courage and the freedom of the player.

Meticulous research by Arabists, Romanists, musicologists and musicians has been growing and has brought a glimpse of the wealth of influences of Arab and Judaeo-Spanish musical cultures from medieval times until the time of romanticism. Spanish musical groups such as Gregorio Paniagua’s Atrium Musicae (1967-82), Cálamus (1980-1995), or Begoña Olavide’s Mudéjar since 1993 and my own group Música Antigua since 1994, have experienced the performance of this frontier world. With this work Felipe Sánchez’s Axivil takes a further look into the musical sources of the 15th and 16th century songbooks, under the influences of Andalusi-Maghrebi music and music from the Muslim Orient.

I congratulate Felipe for all this and I would like to give six reasons for my positive evaluation of his results:

1- The capital importance of rhythm, taken from the Andalusi world.

2- The richly diverse timbre, expressivity and colour of the instrumentation together with the ornamentation and the moments of free improvisation.

3- The choice of the solo voice, natural Mediterranean singing exposed through the wealth of technical resources found in the Flamenco tradition that deliberately moves away from post-baroque vocal education.

4- The combination of the soloist and the rest of the voices in a polyphony that is both correct and surprisingly natural.

5- The expressive force of the instrumentalists, where technique and experience (artistic presence) are revealed in many other types of musical style.

6- Felipe´s musical arrangements that breathe life into the reading of this selection of old well-known scores.

Eduardo Paniagua

PERFUME MUDÉJAR

I can promise that it is not intentional, but all the repertoires of AXIVIL end up being difficult to classify. Records sit on shelves in the shops, in sections and under headings where it would never have occurred to us to look, either to me or to many of the other people I have talked to about it. This is not something I have ever boasted about and I do not wish to appear as though I am doing so now – it is more of a problem – but it is a blatantly obvious fact that the Spanish musical heritage is full of nooks and crannies that ooze art in abundance that is difficult to catalogue using 21st century categories and names.

In Spain the mudéjar style is identifiable in architecture, in the marvellous minor arts, in gardening, in gastronomy, and even in the Castilian language which has absorbed certain words that come from Arabic, not to mention place names…but what about music? In music we have no choice but to research the Christian-Occidental sources of our past and study what is left of the music created in our Middle Ages by the Spanish people of Muslim culture, that is to say Andalusí music. Music that travelled with the people who moved in waves to north Africa and is now preserved in the oral tradition in Algeria, Tunisia and above all in Morocco.

It was not difficult to select a repertoire that could transport us to that mysterious mudéjar musical world, because there is already an unmistakeable PERFUME in the melodies, the rhythms, the use of intervals and the “air” in romances like The Morning of St. John, The Moorish King Rode Up and Down, From Antequera or Three Dark Maids. A PERFUME only found in songs created on our peninsula, although they are songs that are perfectly assimilated in the Christian-Western musical tradition.

In what proportion is the Hispano-Muslim culture present in these songs? I must say that I do not know and I do not intend to find out. I can only say that for a musician, the opportunity to mix musical and stylistic sensations and historical events almost unconsciously stimulates musical and stylistic enthusiasm...all that remains to be done is to tie everything together and make music.

The next step was how to make that perfume really smell and not just be a private experience sitting on my desk. I imagined mudéjar sound to be similar to the sound produced by present day Andalusí orchestras from Morocco but with the pertinent mixture of Arab and occidental instruments that existed in the Spain of the 15th century. In fact, in the few images that I have seen of Moorish musicians they hold Christian instruments in their hands, and similarly, there are many paintings and frescos of angels playing instruments that are completely Arab.

The next thing to take into consideration was the type of singing that should be used. Listening to different Andalusí singers, it became obvious that voice technique, embellishment and lastly the very concept of the singing itself exist in an identical or very similar way in Flamenco singing…Another loose end was tied, but there were more reasons to fall back on the help of Flamenco singing. The fact that music like Flamenco exists, born in a western country and still in full swing in the 21st century, is extraordinary. I do not know what relationship it might have with what was being sung in the Spain of the end of the 15th century – if it were known then experts in Flamenco would tell us – but the way in which the singing sounds so natural on this work is one of the things that gives me most satisfaction as a musician.

On the other hand, I cannot find a better way to convey the drama that is packed into these literary gems, the frontier romances, than to call on the indisputable expressive quality of Flamenco singing. Furthermore, when phrases such as “From Elvira's gates to those Of Bivarambla on he goes.” or “who was leaving the Alhambra” or “the Moorish king rode up and down” are heard from the mouth of a Flamenco singer, they always leave a taste that is inalienable.

I do not know whether these songs sounded like this or anything like this at the end of the 15th century, but as well as enjoying their musical beauty, I am deeply moved by the thought that this is more or less how they could have sounded.

Finally, I wish to thank each and every one of the musicians not for their skill – more than demonstrated – but for their dedication. Especially Pedro Sanz, our Flamenco singer, who we took out of his orbit to take him to another galaxy, not far away but unexplored. A journey that needed a lot of work and effort and that Pedro overcame with his best resources: his art. I would also like to thank Pablo Baselga, our sound engineer, for his display of good taste – and he has a great deal – on this recording. Eduardo Paniagua who has put all his experience – which is a lot – at our disposal, and Angeles Burrel, our producer, who has been behind all the decisions – and there were many – that have been made while setting up this project.

Felipe

Compartir

-

Envío gratis en pedidos mayores a 50 €.

Entrega en 5-7 días laborables para pedidos en España, en el caso de envíos fuera de España el tiempo de envío podría ser algo mayor.

-

Todo el trabajo de Pneuma Music se ha realizado en España.

Música medieval española inédita hasta el momento. Sus discos, con formato Digipack de cubierta de cartón y libreto interior (bilingüe + idioma original), quieren acercarse a una obra de arte total.